Man has long excelled at picking on animals and fucking up the environment, a dismal trait I’m fine with as long as it generates good eco-horror movies. This sub-genre is staggeringly rich and diverse, tackling everything from sentient frogs and mutant sea creatures to walking plants and extraterrestrial viruses that powderize your blood. It has undoubtedly produced classics, such as King Kong and Jaws, while also providing the foundation for many other quality flicks, like Summer Isle’s pagan inhabitants deciding the best way to counteract a catastrophic crop failure is to enjoy a virgin pig barbie.

Of course, part of eco-horror’s charm is that it’s also responsible for some of the all-time daftest films in which the most innocuous entities are turned into man-eaters. And by that, I mean the escapades of carnivorous tomatoes, giant bunnies, and oversized slugs and worms. These days the trend is to not only embrace such absurdity but to up the ante to fantastic extremes. Don’t be surprised to stumble across enormous, lava-breathing tarantulas (Lavalantula) or shark-spewing tornadoes (Sharknado). Whatever the case, eco-horror has fascinated filmmakers pretty much from day one and remains an astonishingly popular way to explore climate change, pollution and disease.

Island of Lost Souls (1932)

I’m no film historian and have little idea if eco-horror originated in 1932 but that seems like an impressively early enough point to begin. Don’t be put off by Souls being the best part of a century old for this pre-Code cult flick has plenty of bite and a great central performance.

Charles Laughton plays Dr. Moreau, a man so bonkers he wears a three-piece white suit and tie all day long in the tropics. Having begun his career by speeding up plant evolution, like any mad scientist worth his salt he’s gone on to develop that worrying tic called ambition.

Grandiose ambition.

Or as he tells a shipwreck survivor on his lush, volcanically enriched South Seas island: “Why not experiment with the more complex organisms?” Soon he’s fanatically dedicated to transforming animals into people via blood transfusions, plastic surgery and a whole gamut of agonizing procedures.

Pretty sick, huh? With his terror-inspiring House of Pain and indifference to suffering, this guy is a Mengele forerunner. I love the way there’s no conceivable point for turning animals into people (other than to see if it can be done) just like it was senseless for the Nazi doctor to sew children together or inject chemicals into their eyes.

Not that Moreau sees it that way. He’s actually pretty chuffed with his pioneering scientific genius, the latest example being Lota, the Panther Woman. She’s his pride and joy, as well as the only woman on the island. Now I’m against this kind of appalling animal experimentation, but I have to admit I am intrigued by the sexual possibilities of turning a panther into a slinky, feline she-creature with limited intelligence and speech. Just imagine: after you’ve done the bizzo you could tether her to a post outside your home and have a pretty nifty guard. Hmm, did I go too far there?

Anyway, this is an eerie, seventy-minute movie built on sadism. Vivisection, madness, death and screams of pain abound. With his neatly trimmed facial hair, clipped tones, obvious intellect and penchant for cracking a bullwhip, Moreau is a fantastic character. He’s the supreme puppet master, drunk on power and control, although he does take time off to sip tea. Watch out for his classic line as he stands in the half-shadows, an observation that helped the hugely controversial Lost Souls cop a decades-long ban in some countries: “Do you know what it means to feel like God?”

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953)

In the early years of the atomic age, it was little surprise that filmmakers couldn’t get enough of cautionary tales about the bomb.

“Every time one of these things goes off I feel as if we’re helping to write the first chapter of a new Genesis,” a scientist says moments before detonating an explosion in the Arctic Circle.

“Let’s hope we don’t find ourselves writing the last chapter of the old one,” another egghead replies.

This time round such an Earth-quaking event unleashes a newly thawed Rhedosaurus that’s been blissfully dozing in the ice for one hundred million years. Yes, I know that’s beyond the wildest dreams of the most dementedly optimistic cryonicist, but it’ll have to do as the premise for this stodgy outing. However, the cop-eating, rollercoaster-wrecking amphibious beastie is early testament to Ray Harryhausen’s astonishing talent, especially when it rises out of the ocean, clambers onto a rocky outcrop and wrecks a lighthouse.

Beast’s main claim to fame, though, is being the first bomb-annoyed giant monster flick, a frontrunner directly responsible for inspiring 1954’s iconic Godzilla. A year after that Harryhausen was busy pissing around with a giant radioactive octopus in It Came from Beneath the Sea.

Them! (1954)

“Ants are the only creatures on Earth, other than man, who wage war,” an expert tells a top-secret taskforce that’s been set up to battle some bothersome giant ants. “They campaign, they are chronic aggressors and they make slave laborers of the captives they don’t kill.” Fair enough, but that doesn’t mean a good flick can be made about them.

Them! was the first big bug creature feature, but it’s a pompous, meandering dud full of ham-fisted dialogue. Typical of its failings is a machine gun-wielding cop who blows fifty holes in the first monstrous ant to turn up, only to lower his smoking weapon and ask: “What is it?” Huh? Presumably he can identify a normal-sized ant, so why’s he struggling when the fucker’s right in front of him and eight feet long?

Anyhow, radiation’s the culprit again, but whereas the Rhedosaurus holds up thanks to Harryhausen’s magic, the stiff, mechanical ant models are devoid of dexterity and speed. It’s telling that the best part of Them! is the mildly suspenseful opening half-hour in which the sugar-stealing darlings don’t appear. As soon as one shows up everything goes to shit.

Twenty years later another attempt was made to make ants frightening with Phase IV. They remain the same size in this one, but super-clever. Are you scared? No, me neither. A burst of solar activity or something has changed their behavior so that all the different species unite and decide to attack. Two po-faced scientists set up a hi-tech dome in the middle of the Arizonian desert to investigate, but soon those brainy insects are scaring horses, blowing up generators, causing cars to crash and short-circuiting computers. Phase IV features some nicely composed shots while its sense of isolation gives it a similar feel to that outback classic Walkabout, but it stretches absurdly all the way. Some of the ants’ acting is very good, though.

Then came 1977’s Empire of the Ants in which a bunch of superimposed ants snack on leaking barrels of toxic waste, surround pre-Dynasty rich bitch Joan Collins and attempt to come up with a solution for typecasting.

Conclusion? Just like violent vegetation movies are rubbish (1962’s Day of the Triffids, The Vines, The Happening), don’t go making ant stuff, either.

The Birds (1963)

The Birds is regarded as classic Hitchcock, although I feel without a shadow of a doubt that it’s nowhere near his best. The titular creatures inexplicably start attacking the inhabitants of a small Californian seaside town, perhaps driven mad by a diet of discarded burgers and having to witness Tippi Hedren’s acting. Nothing convinces here. There’s a ridiculously contrived pet shop opening, terrible special effects, a po-faced ornithologist spouting off in a diner, and the characters doing nonsensical stuff like leaving their indoors haven to wander outside. Most of all, apart from one great bird’s eye view of a fire-engulfed petrol station, it’s boring right through to its non-ending.

Vicious sparrows…? Oh, fuck off, Alfred.

Planet of the Apes (1968)

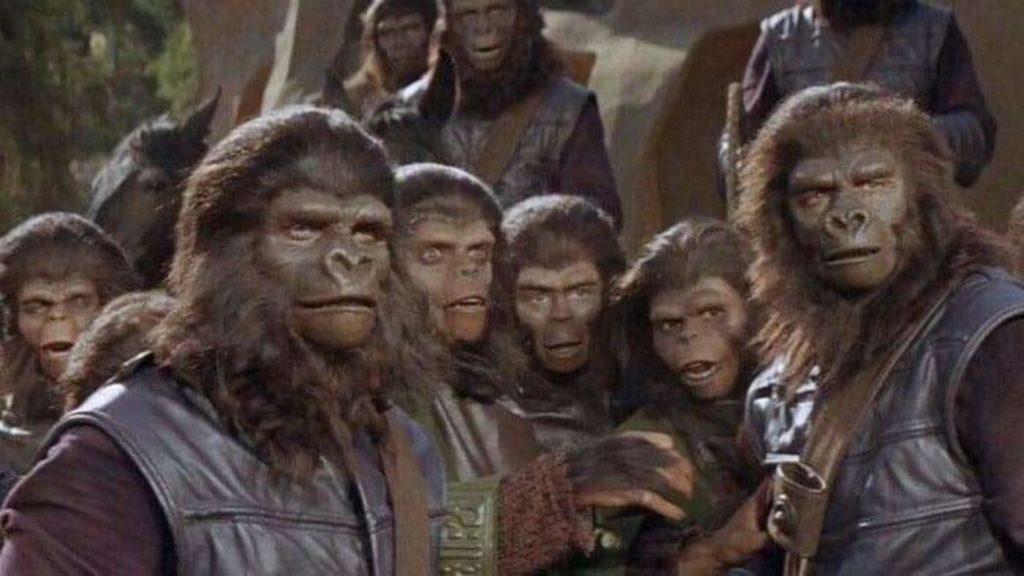

There seems to be a fair chunk of people who insist the book is always better than the movie. As a level-headed chap, whose bouts of homicidal egomania are definitely on the wane, I take things on a case by case basis. However, I will say Pierre Boulle’s Monkey Planet is inferior to Franklin J. Schaffner’s remarkable flick. Monkey Planet is a short, unsatisfactory read with cutesy bookending, but please don’t think I’m having a go at Mr. Boulle. I’ll always be grateful to the guy for coming up with such a brilliant premise. If he hadn’t put pen to paper, we would never have got the newly crash-landed Charlton Heston musing two thousand years from now: “I can’t help thinking that somewhere in the universe there has to be something better than man.”

So why is the iconic movie a hundred times better? Four reasons: racism, vividness, nastiness and its extraordinary ending. At their core both works are about racism, but Apes produces one of the greatest-ever leaps of imagination. There’s simply no better movie out there dealing with prejudice in such an ingenious and memorable way (and that includes Blazing Saddles).

Apes is able to explore racism so well because it adds layer after layer to its satirical source material, thereby creating a much more convincing simian society. Every aspect is superbly thought through. Chuck in the excellent sets and costumes, as well as the groundbreaking makeup, and you get a wonderfully realized upside-down world.

Thirdly, the book lacks brutality. This has always surprised me in that Boulle suffered two years of bloody grim, life-threatening custody during WW2. His personal experience of degradation is only touched upon in his novel whereas Apes is seriously brutal. The savagery begins as soon as the rifle-wielding apes arrive on horseback, beating the cornfield’s long grass in a bid to round up as many of their human prey as possible. From here on it’s all halters, bullwhips, clubs, grinning hunters posing next to piles of corpses, jails, strung-up captives, lobotomies, experimental surgery, racism and talk of extermination.

Christ, it’s so human.

Schaffner directs with real flair, occasionally finding disorientating camera angles to reflect Heston’s acute bewilderment. Dwarfed by the forbidding landscape, the passage of time and his gradual understanding of the mind-boggling events, he gives his most famous performance. Then there’s his classic dialogue, such as “It’s a madhouse! A madhouse!” and “You cut up his brain, you bloody baboon!” and most famously of all: “Get your stinking paws off me, you damned, dirty ape!” (a line I like to spit out whenever I’m arrested).

Co-written by Twilight Zone genius Rod Serling, it’s no surprise Apes provides plenty of food for thought in depicting its clash between faith and science. It retells the story of Darwin and the virulent objections to his revolutionary theory of evolution. I love the pompous, infuriating religious authorities spouting ‘self-evident’ sacred truths when it’s clear they’ve got nothing but backward bullshit and threats of execution in their determined bid to smother genuine knowledge and progress.

One of the marvels of 60s cinema, Apes is a bold, energetic collision of imagination, intellect, verve and action, as well as being another warning about Man’s radiation-infused yen for self-destruction. God, I haven’t even touched upon Jerry Goldsmith’s menacing score and my fondness for that mute Amazonian hottie, Nova. Plus, no matter how many times you see it, that ending never fails to ignite a tingly sense of awe.

No Blade of Grass (1970)

Set in Britain, this is an inept, poorly acted mess masquerading as an end of the world story. A grass-killing disease has led to famine, cannibalism and chaos. “Do you know what I think caused the virus?” one pontificating pub-goer says. “It’s coz them Chinese fertilize everything with human shit.” Unfortunately, we don’t get any shots of our Sino neighbors defecating on crops so we’ll have to put that particular observation down to racism for, as we all know, the Chinese are actually ruining everything by eating bats.

There’s nothing subtle about Grass, a movie that opens with a lengthy montage of dying Earth images, replete with a boring song that gently tells us things have gone to shit before a voiceover hammers home things have gone to shit.

Still, if you want to see horned bikers on the rampage, real-life footage of a birth, and a mum and her sixteen-year-old virginal daughter gang-raped to groovy sixties music, then this is the one for you.

Soylent Green (1973)

It’s time for some more square-jawed heroics from Chuck Heston.

He’s popped off to the future again and unsurprisingly things ain’t too rosy. Instead of lobotomy-performing apes, he’s gotta deal with overpopulation, pollution, scarcity of basic resources, an energy crisis, a year-round heat wave and his best mate Edward G. Robinson wearing an effete beret. Things are so shite that the mere sight of a stick of celery or a bar of soap can induce rapture.

There’s nothing futuristic about this 2022 vision of New York City. Progress has stalled somewhere in the 70s so that we get crappy computer games, awful interior furnishings and the massed poor having nothing to do except sleep. Interestingly, female emancipation has hurtled backwards. Women are now known as ‘furniture’ in that they’re owned by men and expected to endure a bit of wear and tear. This subtext doesn’t lead anywhere, but back in 1973 it must’ve irked the average feminist.

As for Chuck, he’s a gruff cop who looks like he got blindly dressed in a charity shop. His morals seem a bit dodgy, too, in that he’s happy to ransack a murdered rich man’s apartment while swigging a bottle of all too rare bourbon. However, he’s a dogged investigator, discovering the victim is a key man in the food production industry with political connections. Suddenly doors start closing and Chuck’s being followed. Or as he concludes: “Something stinks here.”

Soylent might be a little unfocused, but I’m fond of it. It’s got two memorable scenes: a food riot that sees protestors literally treated as garbage and Robinson’s sendoff (an assisted journey into death replete with vivid images of the Earth’s former bio-diverse richness) made all the more poignant by the distinctive Double Indemnity actor knowing he was terminally ill in real life.

And, of course, while Apes has the famous ending, Soylent boasts that much-loved last line.

Jaws (1975)

It’s always amazed me that it took until the mid-seventies for filmmakers to get round to doing a proper shark story. After all, real-life attacks have long mesmerized the public (Jaws mentions the 1916 Jersey Shore fatalities while the 1945 sinking of the USS Indianapolis prompts one of cinema’s great monologues). Given that a shipwreck victim gets munched as far back as 1932’s groovy The Most Dangerous Game, why the delay in putting a great white or tiger front and center?

Well, I don’t have the answer, but the enormous success of Peter Benchley’s very readable novel ensured an, ahem, sea change.

And thank fuck for that.

Blessed with the most memorable opening in cinema, Jaws is packed full of superb moments. You know the ones. Fingernails being dragged down a blackboard, an impromptu jetty tow, a severed leg sinking to the ocean bottom, an underwater head popping out of a holed hull, and a grieving mother delivering a public slap. Its tautly directed two hours remain a magical watch.

Former New York cop Martin Brody (Roy Scheider) has moved to New England’s Amity Island for a quieter life, although he still has to deal with rampaging pre-adolescents karate-chopping picket fences. Things don’t improve when a missing skinny dipper turns up in less than pristine condition on the beach. I love the way the water-hating Brody looks down at the remains of her crab-covered corpse, takes off his glasses and glances out to sea, as if he already knows there’s a reckoning to be had.

The lethal attacks continue, mainly because the shit-kicking mayor puts the mighty dollar above lives. Indeed, Jaws is excellent at illustrating people’s stupidity when faced with a frightening threat, its first half offering numerous examples of knee-jerk reactions, half-assed solutions, irrationality, incompetence, hoaxers and exploitation.

It’s not long before Brody’s hooked up with a youthful marine biologist Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) and a crusty, charismatic, possibly deranged seadog Quint (Robert Shaw) to hunt the 25ft, three-ton shark. “What we’re dealing with here is a perfect engine,” Hooper says. “An eating machine. It’s really a miracle of evolution. All this machine does is swim and eat and make little sharks.”

The interplay between the three seafaring misfits is the stuff of legend, especially when they drunkenly compare scars. This lighthearted bonding leads into Quint’s mesmerizing recollection of a top-secret maritime mission that ended in disaster with hundreds of men in the water able to do little against an army of marauding sharks. Not sure if I believe him, though, when he says he once saw a shark eat a rocking chair.

Director Steven Spielberg conjures up a marvel on a $9million budget. Some stuff is simple, like the departing Orca being viewed through the gaping skeletal jaws of one of Quint’s earlier conquests. At other times Spielberg repeatedly generates compelling drama through the antics of floating yellow barrels.

Then there’s the more tricky stuff. Good grief, the sequence with a panicking Hooper in the anti-shark cage is as tense and attention-grabbing as anything I’ve ever seen. But that’s Jaws for you. It’s simply brilliant at mastering so many elements, such as riveting action, sly comedy and perfect characterization. Throw in that score and you not only have Spielberg’s best movie but the greatest eco-horror movie of all time.

In the wake of Jaws’ unparalleled success, the whole eco-horror thing received a massive boost as filmmakers scrabbled to come up with their own take or cash in with the most basic rip-off. One of the first was Orca: The Killer Whale, a fascinating fishy fuckup that features a gorgeous pre-stardom Bo Derek and the slightly less sexy Indian giant Will Sampson. You might remember him humanely smothering a lobotomized Jack Nicholson in the days when he could recognize a decent script. Frankly, after watching this turkey, he should’ve stayed inside the nuthouse or at least smothered his agent.

Nothing works in this strangely watchable dud, especially its preposterous dialogue. Listen to this early snatch from whale expert Charlotte Rampling (!) illuminating a typical killer whale trait: “Like human beings, they have a profound instinct for vengeance.” Hmm, don’t think so, love, but I’ll go along with it for the movie’s sake.

Richard Harris stars, apparently unbothered that his Ahab-style character is a confused cunt. He wants to capture a whale to sell to an ‘aquarium’, but thinks an explosive harpoon is the way to go. Five minutes later he’s slaughtered a pregnant beast as her anguished mate vows Bronson-style revenge. Next it’s killed one of his crew and sunk a couple of boats in the harbor. How long before it’s slithering down the high street packing heat? Understandably shaken, Harris seeks answers from the church. “Can you commit a sin against an animal?” he asks a reverend, who doesn’t even need to check the bible’s killer whale section. “You can commit a sin against a blade of grass,” comes the reply.

Bloody hell, the magnitude of this one’s ineptness is off the scale. Mind you, it deserves credit for refusing to blink during its ninety minutes of face-slapping lunacy. I’m just disappointed it wasn’t called Orca: The Face of Death or Orca: The Evil That Whales Do. At least we know where that third Jaws sequel dredged up its farcical storyline.

Next off the conveyor belt was 1978’s Piranha. There’s a glimmer of an idea here as the wee beasties in question are the result of Operation Razor Teeth, a top-secret Vietnam-era governmental attempt to breed a super-weapon to use against the VC. Its opening fifteen minutes promise some tongue-in-cheek fun, but its bursts of piscine savagery soon wear out their welcome.

Right, I’m done with bad fishy flicks and can’t be bothered to sit through the unappealing giant octopus spectacular, Tentacles. Let’s try a couple of flicks from Down Under.

Long Weekend (1978)

Australia first had a go at eco-horror with 1977’s Aborigine-flavored The Last Wave. Its main merit is showing Aborigines are just as dumb as Christians and all those other pious nitwits when it comes to banging on about that elusive (but apparently ever-present) looming apocalypse. And so we get freakish weather and bad dreams and… Oh, I don’t care. Wouldn’t it be nice if one of these religious or quasi-religious bunch of numpties came up with a prediction in which God was chuffed with mankind’s progress and wanted to hold a lovely big barbecue to celebrate? Instead, Last Wave goes the traditional, catastrophe-just-round-the-corner route. Sure, it offers the odd creepy shot, but gets sunk by ropey acting and a plodding pace.

Much, much better is Long Weekend. Written by Everett De Roche, who went on to pen the bacon-and-tusks-flavored Razorback, this is one eerie motherfucker. A squabbling Aussie couple goes on an isolated camping trip. Peter’s an arrogant, careless bastard, the sort of trigger-happy bloke who flicks lit ciggies out the car window and chucks beer bottles into the surf to shoot at. His wife Marcia is hard work, too, in that she’s a brittle, resentful, tantrum-throwing adulterer.

The thing that sets Long Weekend apart is its abortion underpinning. Peter and Marcia’s three-day break is designed to bring them back together as they’ve spent the last couple of months subconsciously trying to deal with the deliberate destruction of their unborn child. Sex has died, arguments have increased, and they’re heading for the rocks.

During their holiday Marcia becomes fascinated with an eagle egg while Peter finds a doll on the beach and an abandoned child’s tea set in the bush. They hear animal cries that sound just like a baby. Best of all, is when Peter investigates a submerged vehicle and glimpses a child-like entity on its back seat.

Long Weekend has the potential for Jaws-style attacks, but prefers a much subtler, nuanced approach that worms its way under your skin. It’s steadily paced with excellent photography and good performances. It also manages to find a satisfying ending.

Humanoids from the Deep (1980)

I’m afraid my objective journalistic analysis of moviedom is about to slip with this one. You see, I have a personal reason for Humanoids’ inclusion that has nothing to do with its suitability or quality. I just enjoy watching one of its cast get killed.

Over and over.

The dude’s name is David Strassman and he’s an enormously successful ventriloquist/comedian. You might have heard of him. I briefly met him in 1996 and I can still remember his disdainful handshake that transmitted a flashing neon message to my brain: You’re no one so I’m not gonna bother with you.

Then he was off to spend time with more worthwhile people.

The fact his withering verdict was true did not soothe my hurt. I just watched his sold-out show instead, determined not to be entertained while the painful memories of that fateful handshake began to turn septic. The years passed and my desire for revenge only intensified.

Then I happened to catch Humanoids and was taken by surprise to see a youthful Strassman pop up in his only movie to date.

In a tent on an isolated beach with a gorgeous chick.

Bastard.

Then she peels off her top to reveal some bloody impressive norks.

Double bastard.

Now she’s fully nude.

Life’s so unfair! Do I have to watch my transgressor doing the sort of stuff with a hot babe that only exists in my tortured dreams?

But then, lo and behold, things get miraculously better.

A monster rips its way into the tent, the terrified girl screams, and Strassman is sporting a hideous shoulder wound.

Justice for Davey!

Unfortunately, the monster loses interest in mutilating Strassman any further and instead lumbers after the fleeing naked girl. I guess I can understand its priorities.

Humanoids is a prime example of schlock. Short, filled with boobies, explosions and continuity lapses, it’s the sort of flick any teenage boy appreciates. If you want the plot, big business has inadvertently released genetically enhanced salmon into the surrounding waters, resulting in coelacanths feeding on them and abruptly turning into rape-loving dog-haters in thick rubbery suits.

Well, count me in.

This is not a good movie, but it is gory fun. The world needs more tiara-wearing, bare-breasted beauty queens battling ravenous mutant fish-men. Plus, there’s half-decent direction, an effective score, appealing scenery, racial undercurrents, a reasonably convincing depiction of life in a Californian coastal town, an upright female scientist who specializes in stating the bleeding obvious, and a brazen Alien rip-off moment.

Not to mention Strassman’s demise. And even though his pretend onscreen death happened sixteen years before belittling me with his disapproving press of the fingers, I’m still gonna put it down to a particularly deserving case of karma.

Cujo (1983)

As we know, those never-ending Stephen King adaptations have been doing their best to smother cinema for a while now. Back in the early days there were classics like Carrie, The Shining, The Dead Zone and Misery, as well as half-decent, non-horror stuff like Stand by Me and Shawshank. These days we get junk (It and Doctor Sleep), mediocrity (1922), and bum-numbing epics in which Tom Hanks can’t piss properly (The Green Mile). How long before a studio gets hold of the great man’s shopping list and runs with that? Couldn’t be any worse than 2019’s Pet Sematary.

Cujo, on the other paw, is neither great nor crap. It has a professional gloss in the directing and acting departments, but misses the mark partly because its disparate elements (such as adultery and dodgy cereal) don’t gel.

Dee Wallace is married to a nice, good-looking guy who’s not only kept himself in shape but is a brilliant father to their little boy. Her response? To drop her panties for the local bearded stud. Meanwhile, the nearby white trash mechanic’s St. Bernard is bitten on the schnozzle by a rabid bat. Dee gets car trouble and so pops out to get it fixed, resulting in the nutzo mutt keeping her pinned in the vehicle.

Story and music-wise, Cujo doesn’t feel like a horror movie for its entire first half. However, once the pooch becomes a postman’s nightmare, the animal trainers do their job well. It’s a convincingly skuzzy, mad and miserable beast, especially when it begins headbutting the sweltering car and chewing off door handles. Still, there’s only so much mileage in such a flimsy setup, even if I did appreciate Dee barking: “Fuck you, dog!” It would be nice if her lengthy confinement could in some way be interpreted as ‘punishment’ for her shitty decision to enjoy extra-marital cock, but the screenplay’s far too standard for anything so daring. Instead, it’s a simple, small, story.

Too simple, too small.

Razorback (1984)

“Razorbacks. Vicious, shit-eating, godless vermin. God and the devil couldn’t have created a more despicable species.”

Razorback didn’t do great business on release, but has deservedly picked up a fair few fans since. It boasts superb cinematography and many attention-grabbing shots. Just look at its opening frames of a kangaroo grubbing around by a barbed wire fence silhouetted against an apocalyptic setting sun. Images of savage beauty abound, a feature that sometimes gives the outback landscape an extraterrestrial feel.

In a telling echo of Australia’s infamous dingo baby case, nice old guy Jake Cullen (Bill Kerr) is looking after his grandkid when a massive wild boar smashes through the wall of the house and carries off the tender treat to devour. Barely anyone believes his account of events until two years later when a no-shit female investigative reporter, who specializes in exposing animal abuse, also vanishes…

Razorback packs a terrific amount of incident into its opening twenty-five minutes. It’s strong on thrills, mood and atmosphere so we get everything from a nighttime car chase and the threat of rape to a shaggy camel sticking its head through a pub window to grab a can of Coke. Texas Chainsaw fans should enjoy the dodgy meat packing plant, the sense of isolation, the heat and dust, the scattered animal bones, and some of the uncultured, possibly insane locals.

Director Russell Mulcahy, who at this point already had an enormously impressive CV helming innovative pop music videos, knows what he’s doing and gets mostly good performances from an entertaining cast. I also enjoyed the dialogue such as “What’s up your hole?”, “Haven’t seen a taxi round here since about 1953 and he was lost”, “One fart and you’re a hamburger” and “Wakey! Wakey! Hands off, snakey!”

The outback has provided the setting for some very good flicks, such as The Proposition, Mad Max 2 and especially Wake in Fright. Likewise Razorback capitalizes on its location. It’s a distinctive slice of eco-horror with an uncompromising edge and very strong visuals. Keep your eyes peeled for an outstanding piece of comedy involving a fast disappearing TV set.

Safe (1995)

I guess unleashing genocide on gypsies or Jews is frowned upon these days, but I can’t see much wrong in wiping out rich suburbanites like Carol White and her pathetic, whiny ilk.

You see, there’s no point to Carol’s exceptionally comfortable life. She calls herself a homemaker in a fancy bid to cover up the fact she doesn’t work, knowing full well housewife doesn’t sound too impressive when other women with a bit of get up and go are running businesses, piloting jumbo jets or winning Olympic medals. Carol spends her blank days having manicures at the hairdresser or getting upset when the wrong-colored couch is delivered to her fastidiously neat and tidy home. She doesn’t enjoy sex.

Or anything else for that matter.

She’s stiff, brittle and self-obsessed. Even though she’s in her early thirties, the most energetic thing she can muster is a gentle burst of Madonna-accompanied aerobics. Otherwise she’s a pale human tortoise, convinced she’s under ‘a lot of stress.’ Her circle of cookie cutter friends amplifies her vacuous, pampered shortcomings. They talk about fruit diets and self-help books while dithering over decaf or herbal tea. At a baby shower Carol asks one bestie if she wrapped the present herself.

“Oh God, are you kidding?” the friend replies with an embarrassed laugh. “I wish I were that creative.”

Armageddon, come Armageddon! as Morrissey might say.

But at least Carol’s buried self-loathing is subconsciously allowing her to grasp she’s a non-entity. Her body wants out and is starting to shut down. First it’s a nosebleed, then bouts of puking. Panic attacks follow. Her doctor can’t find anything wrong and suggests a shrink, but feeble-minded attention-seekers like Carol are never likely to truly grasp their irrelevance.

No, she prefers to blame her symptoms on the environment. Toxins, pesticides, exhaust fumes, even her mystified husband’s cologne… You name it, they’re the root cause. And, of course, there’s a growing army of pseudo-scientific rip-off merchants standing by with their hippy self-love bullshit to convince her she’s got an ‘environmental illness’ and needs to establish ‘toxic-free zones’. Or as one tells her: “There are 60,000 chemicals in our environment, but only ten percent tested for human toxicity.”

As you can tell, Safe is not an action-packed thriller, but an overlong, quietly intriguing peek into neurosis and paranoia. Director Todd Haynes draws a terrific, anxiety-ridden performance from Julianne Moore, who shows how a seemingly intelligent, rational type can get sucked into such a mind-fucking vortex. Sure, there’s a possibility Carol’s body is reacting to pollutants, but I’d rather believe such a psychosomatic waste of space needs shooting.

Great, I’ve turned into a Nazi.

Waterworld (1995)

The first shot we get is Kevin Costner having a slash, although if Waterworld wanted to open with a more representative act of its quality he’d be shitting.

Well, maybe that’s a bit harsh. Waterworld is a big budget mess that often feels like a sodden Mad Max 2, but its campiness and energetic direction just about keep it afloat. However, its 130 minutes contain far more chuckles than thrills.

For a start there’s Costner himself. Presumably he has his uses (though I’d be hard-pressed to name one), but he’s a bad fit as a surly, eyeball-eating action hero. I mean, he does his best swinging through the air like Tarzan and, er, rescuing tomatoes, but he’s continually undermined by the costume department having decked him out in striped trousers, a topknot and a barnacle earring. Oh yeah, then there are the gills and webbed feet which enable him to swim so fast underwater he can leap dolphin-like out of the drink.

It’s a tricky movie to take seriously, you know? And after factoring in its $175 million budget, you start to think the western world’s priorities are a little out of whack and maybe such an obscene amount of cash should be used to feed the poor or at least given to me.

Anyhow, it’s five hundred years into the future and all that important ice stuff has melted. Dry land is as rare as a good Dire Straits album cover. Kev’s become a nameless drifter, although at one point he’s amusingly labeled a ‘Gentleman Guppy’. He’s a hard-bitten loner on a fancy boat who trades dirt. And no, I don’t mean porno mags, butt plugs and incriminating info. I mean actual dirt. After inadvertently getting caught up in Dennis Hopper’s attack on a trading post, he escapes with a brat who’s got a map tattooed on her back. Hopper badly wants that map, although fuck knows how he learned of its existence in the first place. He’s convinced it will lead him and his followers to the long-desired dry land, so the chase is on.

Hopper doesn’t come out of this one too well, either. Clad in a codpiece and shoulder pads, he looks like a down-market, one-eyed Gary Glitter. Whereas Gary was backed by the Glitter Band, Our Den leads The Smokers. Can you guess how they get their name? Mind you, given that the average corner shop is thousands of feet underwater, I have no idea how he’s obtained a constant supply of Benson and Hedges Superslims. In fact, he’s got so many ciggies he even offers one to the map-adorned kid. “Never too young to start,” he says with a gleam in his eye.

My God, everyone’s lost at sea in this increasingly tongue-in-cheek, way over the top piece of flotsam. It’s gibberish yet somehow perfectly predictable, featuring a shit load of explosions, an over talkative child badly in need of drowning, a pinch of semaphore, and Hopper describing Kev as a ‘turd that won’t flush’.

Amen to that.

We’re told Mother Nature nurtures us but you try telling that to the hapless heroes of this deeply unnerving existential flick. There’s no ‘villain’ here, no man-made threat, no example of the radioactive chickens coming home to roost. Instead it’s a case of two stranded ordinary Joes trying to deal with the environment’s ego-squashing indifference to their horrifying plight.

Daniel and Susan (Blanchard Ryan and Daniel Travis) are two hard workers who take a much-needed diving trip. Unfortunately, the dive master screws up the headcount of the returning divers, leaving the poor lambs to resurface and find their boat gone.

Land cannot be seen. They’re caught in a current. The sun keeps beating down. There’s no food. And the local wildlife is growing increasingly unfriendly…

Open Water has the simplest setup of any movie I’ve seen yet it’s devastatingly effective. It really is a nightmare scenario, its creeping horror generated by little more than two decent human beings bobbing on the warm ocean waves.

“We’re gonna get through this,” Daniel reassures his girl at one point.

But you sense they’re not.

Tormented by the possibility of rescue from distant boats on the horizon, it’s not long before cramp, vomiting and jellyfish stings start to snuff out hope. Neither can believe the situation.

“The best part is we paid to be out here,” Daniel shouts amid the arguments, recriminations, rage, terror, and the inevitable I love yous. “We paid those incompetent fuckers to drop us out in the middle of the ocean.”

Susan’s bleakly funny response? “I wanted to go skiing.”

Unbearably tense at points, this is survival horror of the highest caliber. It’s fascinating how Daniel is aware of their puniness in the face of such a vast, eon-spanning wilderness but still bellows into the void, apparently determined to assert the weight of his existence as the circling sharks draw ever closer.