EDITOR’S NOTE: YouTube is now streaming some great movies, in totality, with ads. Here is one that Matt reviewed. Enjoy.

Despite what I might say in the remainder of this review, I liked The Last Samurai. Even with its 2 1/2 hour length, it moved quite well and I was engaged throughout. Director Edward Zwick, as always, creates a distinct world inhabited by fascinating characters and stunning visuals. In fact, the battle scenes are extraordinary; both lush and horrifying, which creates the bizarre sensation of romanticizing warfare while simultaneously rubbing our noses in the bloody horror. It is an epic with heart, and everyone involved deserves hearty congratulations for meticulously crafting a cinematic treat that never ceases to be entertaining. That said, I cannot say that the movie is a complete success. It is solid without being superb; lightly intoxicating while failing to fully engage my mind. And while it hits all of the expected emotional cues, it does not reach the intellect, preferring to lean on tried-and-true Hollywood formulas when a bit of daring would have carried it into the realm of a modern classic.

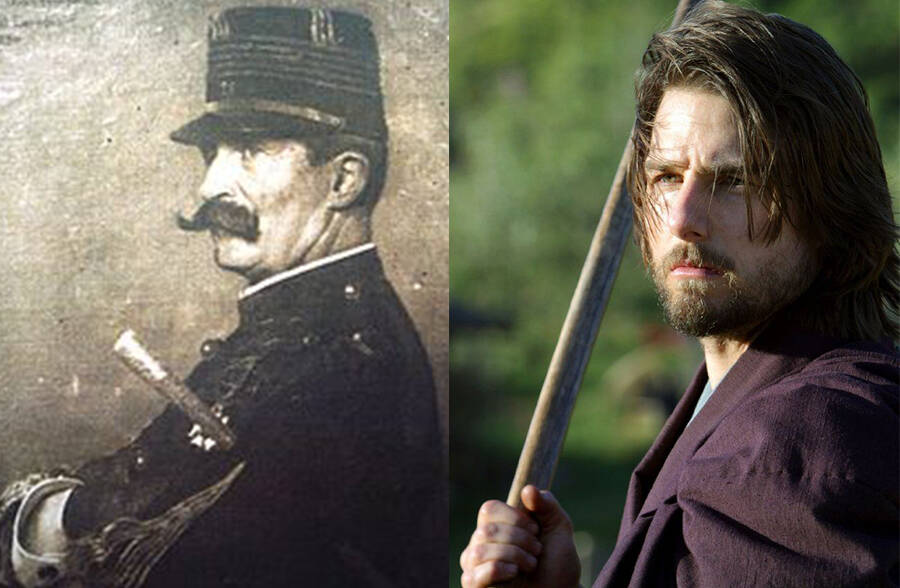

The first problem is that the story is told through the eyes of Nathan Algren (Tom Cruise), a haunted soldier who has seen the slaughters of the Civil War and post-war Indian campaigns and is forced to live with the horrors. He spends his days on the “circuit,” helping to sell firearms by telling tall tales about Indian savagery and white heroism. We meet him at one such speech when he is called by an old friend to help put down an uprising in far away Japan. At the very least, Algren reasons, the pay is good and he will have the opportunity to leave his troubles behind. His job, along with that of his superior (and personal foe), is to train an army of conscripts to put down a samurai rebellion, which will in turn strengthen the Japanese empire and its burgeoning status as a military and economic superpower. The militarists and “moderns” in the government envision a nation of firepower and finance, which in 1877 was well in advance of the 20th century incarnation of Japanese might.

Almost immediately, we see the stakes – the humble, honor-bound samurai warriors, still beholden to their beloved Emperor, are being exterminated in the name of progress by a group of businessmen, who themselves manipulate, rather than serve, that same Emperor. Admittedly, this is a great premise for a film, especially one that plays itself as a thinking man’s epic. However, by forcing us to look at this situation through the eyes of a white American, we never get as close to the Japanese people as one would hope. Despite the plight of the samurai, they are always at a distance; a fascinating, yet difficult to understand, persecuted minority. Tom Cruise will certainly bring in the box office, but for me, he was yet another example of Hollywood insisting that we cannot relate to a story unless it has as its protagonist a friendly white face.

Cruise is effective and I wasn’t intimidated by his star power, but I did resent his presence. And it is here that I make a larger point as to why the film wasn’t as good as it could have been. Zwick establishes early on that the samurai are victims of a new order; typical underdogs facing a numerically superior, yet morally inferior, foe. The music and perspective (we spend quite a bit of time with the samurai, yet only get snippets of the militarists) inform us of who to root for and based on the reactions of the preview audience, they applauded when it was appropriate to do so. But why indeed are these people clapping? The samurai as presented are a noble people to be sure, but as the average American knows nothing about either Japanese culture or its samurai history, the only reason they are rooting for them is because the movie provides them with no other option.

The samurai are “good” because the film says they are, not because we truly understand what is at stake with the loss of their culture. Are people cheering for the ideals they uphold (when in fact many would be appalled by their fanatical devotion to tradition and the “divine” emperor, a man they would kill themselves for), or the fact that Zwick and his screenwriters have designated them as the men in white hats, and it really doesn’t matter what they are preserving or defending? It could be the right to drink sake or eat unlimited rice balls for all they know. Perhaps it is not the fault of the filmmakers that American audiences are totally ignorant in regards to Asian (or any other) history, but they are obligated to move beyond cheap and easy dichotomies.

When I watch Ken Watanabe, however, as Katsumoto, I realize even more why I would have preferred a full immersion in the samurai world without the Cruise-Filter. He is so magnetic and forceful that a slight comparison to Toshiro Mifune is not completely unwarranted. Mifune is still the god of gods in terms of samurai films (as is Kurosawa, who would flick away Mr. Zwick in an instant as a mere pretender to the throne), but not everyone can be at the top of the list, so it is unfair to always hold others to that standard. For me, this is Watanabe’s film and any emotional outpouring comes from and through him, not Cruise.

Part of me wishes Cruise would have wandered from captivity and taken up arms against the samurai tribe so that he could have been massacred in due course. Still, there could have been more of Katsumoto, and there were times when I felt the film was a bit condescending toward him, almost in the same way Dances With Wolves romanticized Native Americans. We might relate to them as plucky folks battling impossible odds, but they always remain an Other as the film seems to argue that these people are worthwhile merely because Tom Cruise chooses to stay with them.

Other cliches abound, such as the young boy who bonds with Cruise (and cries when Cruise must leave for the last battle), the widow who grows fond of Tom (and who was married to the very man he killed early in the film), and the final confrontation between Cruise and his former superior (it seems a bit much when, amidst hundreds of sword-wielding madmen and cannon blasts, as well as chugging horses and walls of flame, Cruise is able to find just this man and pierce him with a sword). And of course, Katsumoto has a death scene straight from the halls of melodrama (after being hit with enough bullets to kill a regiment), which might affect someone decidedly less cynical than I. And there is a turn of events at the end involving the Emperor and the American ambassador that strains credibility, but it is not necessarily fatal. The battle scenes ooze with blood and gore and are so well choreographed that I nodded with approval throughout. At this level, the film is a triumph. But that was not enough.

The tale of the Western man who is transformed mentally and spiritually by the East is an old one, and one that isn’t necessarily played out. I just simply didn’t believe that what we saw would have changed this particular man, because it is taken as a given that what he finds is what he has always sought. A film should not insist on this, it should “prove” it through demonstration and a realistic contrast. After all, if it is violence that Cruise seeks to escape, he found himself in battles that are the equal of his own Gettysburg and Little Big Horn. Japanese culture might seem quaint and fascinating to Americans in the same way we dehumanize the Amish, but there is enough of genuine substance that the merits of the samurai world should be explained without simplification.

As we know, and as the film tells us, the samurai faded into legend while Japan embarked on a fanatical course that brought it to Nanking, Okinawa, and eventually humiliating defeat at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. So yes, there is lamentation when the samurai lay down their swords in favor of mechanized, murderous modernists. But the film doesn’t give us a full measure of that loss, and asks only that we cry for Tom’s buddy, and hope that we too could be there with him, tending our quiet gardens while the world passes us by.