Sinead O’Connor called her fantastic second album I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, although she could’ve just said I Want What I’ve Got.

But what if you no longer want what you’ve got?

What happens if all your responsibilities, connections and habits are nothing but burdens?

Given the chance, would you cast them aside to begin life again with a new face and identity?

And then make damned sure you didn’t fall for the same bullshit.

This is the juicy meat director John Frankenheimer sinks his teeth into during the superb Seconds. Its opening credits feature discordant organ music playing over images of a continually distorting human face, an unsettling sequence that suggests we’re in for a treat.

Then we start following a middle-aged, troubled-looking man through a New York train station. A note is thrust into his hand, but before he has a chance to ask a question the mysterious other man is gone. His agitation increases, something his wife senses when she picks him up in the car park. She knows it’s got something to do with a phone call he received last night, a phone call from a dead man. Later in their comfortable, well-furnished home she tries to make love but as usual he’s elsewhere, forcing her to slink back to her single bed.

This is a portrait of a jowly, unfulfilled man. The spark’s long gone. His marriage is a ‘polite, celibate truce.’ Whatever dreams he had haven’t come true. Everything’s gray, safe and predictable.

Emotionally and spiritually, the guy’s little more than a walking corpse.

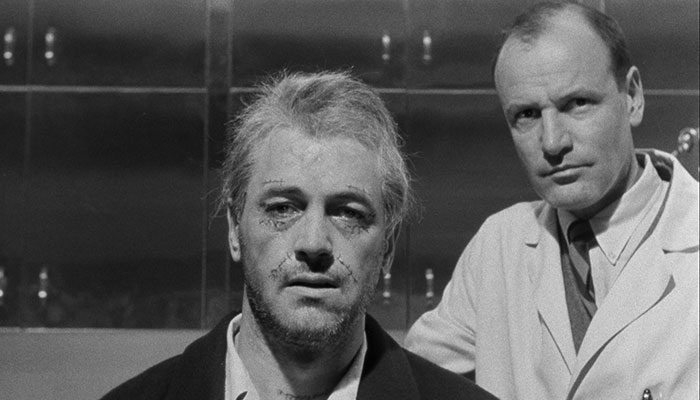

But Arthur (Randolph) has just been put in touch with a shadowy organization that helps people become ‘reborns’, a lengthy process that involves a fake death, extensive plastic surgery and relocation. The company’s associates claim to be ‘waging a battle against human misery.’

And it only costs thirty grand to escape.

Arthur’s not completely convinced, though. After all, it’s a hell of a thing to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Seconds features a few profoundly sad scenes, none more so than when he hesitantly travels to the HQ of his potential savior and tries to come up with reasons not to do it.

“What are you to her now?” a company associate asks about his gentle, faithful wife. “We get along,” Arthur replies in a masterful bit of dialogue that concisely captures the state of their marriage.

Pressed further, he can’t muster a jot of enthusiasm for his banking job, a distant daughter who occasionally writes, or any of his friends.

“What does it all mean?” the associate says. “Hmm…? It can’t mean anything anymore. There’s nothing.”

And so Arthur goes through with his rebirth, relocating to a freewheeling beachside community in Malibu. The organization is thrilled with his transformation into a bachelor painter (played by Rock Hudson). “You are absolved of all responsibility, except to your own interests,” he is told. “Isn’t that marvelous? And remember, you’ve got what almost every middle-aged man in America wants. Freedom. Real freedom.”

Now it wasn’t too long ago I was writing about a horny, bumbling Dudley Moore having a midlife crisis in 10. Seconds covers similar ground, except it replaces the laughs with pure fucking horror. It’s a dark, creepy triumph, its aching sense of existential unease brilliantly captured by an array of odd camera angles and queasy close-ups. It’s particularly good at communicating a sense of stasis and movement in the same shot so that Arthur sometimes stays in the center of the frame, but the background continues to move.

Seconds often feels like a superior Twilight Zone episode given a hallucinatory, feverish sheen. It’s really well thought out, smartly acted and continually intriguing. Most of all, its enduring theme of wanting to start over, of having seconds, makes it timeless.

Watch out for its haunting final shot.