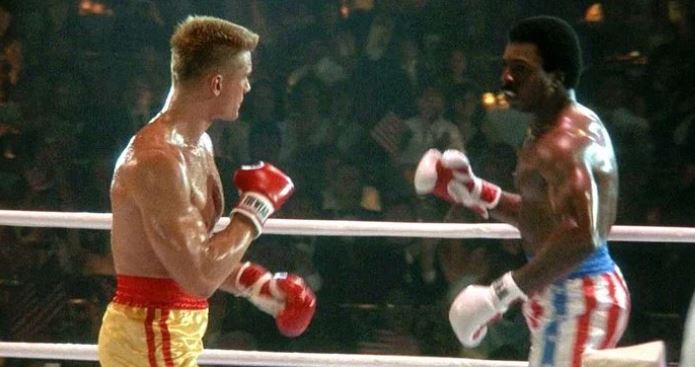

At the beginning of Rocky IV, Rocky and Apollo dance around the ring throwing mock insults but essentially admiring each other’s physiques. It’s one of moviedom’s gayest starts, especially with lines like “I’m gonna whip your butt” and “You really look good for an older guy.” To be honest, it’s a bit of a surprise they don’t just embrace, lock lips and fall in soft focus to the canvas.

Nevertheless, before they start lovingly pummeling one another, Apollo utters a key line: “It’s too bad we gotta get old, huh?” It’s jokingly said, but so well delivered that you can pick up on a tinge of sadness and fear. Apollo, you see, is afraid of aging, having become increasingly aware of his profession’s brutal reality: being in your late thirties means you’re way past your best. And if you can no longer fight at the highest level, then you’re one step closer to death. That’s why he takes on the monstrous, terrifying Drago. It’s his attempt to slay the dragon, to reverse time, to bring back the glory days and, ultimately, to give death the finger.

And, of course, although Apollo says the line to Rocky, he’s speaking for all of us. It is ‘too bad’ the clock is ticking. You don’t have to be an ex-professional boxer to worry about your body and mind degenerating. Let’s face it: no one is looking forward to buying their first hearing aid. And once you’ve popped such a device into your lughole, how long before you end up a frail, semi-abandoned joke in a nursing home?

Aah, the nursing home. No matter how they try to disguise those places, no matter what euphemistic language is employed, we all know what they represent. For example, I recently bought my house from an OAP, who was about to move into a nursing home. I heard through the real estate agent that she was in tears in the hours before leaving, partly because it had been her home for nearly three decades, but also because she must have understood what the relocation meant. The last stop on life’s journey. The end of the line where the Grim Reaper clips your ticket.

Too bad we gotta get old, huh?

Nursing homes appear to be a curiously Western invention. In many parts of Asia they don’t exist or are in their infancy. Old folk there are looked after by family, a noble, heartwarming tradition which has long fallen out of fashion over here. We seem embarrassed by physical and mental decay, and do our best to push it away. Hence, the enormous growth of aged care facilities, places where a visitor might only have to come into contact with the ravages of time once a month instead of daily. Some Asian people I’ve met abroad can’t believe Westerners treat their older family members so cruelly.

But that’s how things are overwhelmingly done in the West. We shunt geriatrics off to a home. What else can we do with them? Well, after being wowed by Terminator 2’s nonstop action back in the early nineties, the world’s greatest-ever stand-up, Bill Hicks, mooted a possible solution. He argued there was no way to top such stunts unless we started using terminally ill people. “Put them in the movies,” he insisted. “You want your grandmother dying like a little bird in some hospital room, her translucent skin so thin you can see her last heartbeat working its way down her blue veins? Or do you want her to meet Chuck Norris?”

Bill then imagined a rapid-fire interchange between a concerned relative and the movie director. ‘Hey, how come you’ve dressed my grandmother up as a mugger?’ ‘Shut up and get off the set. Action! Push her toward Chuck.’ ‘Wow! He kicked her head right off her body!’ ‘Did you see my grammy?’ ‘Son, she’s out of her misery, and you’re about to see the greatest film of all time.’

I’m sure you’ll agree, it’s a tantalizing proposal. Meanwhile, here are seven old fuckers in a conspicuously youth-orientated industry who managed to shine without having their heads actually kicked off.

Professor Marcus Monserrat and Estelle Monserrat in The Sorcerers (1967)

Altruism.

What a wonderful thing.

Wish I had some.

Still, at least Professor Marcus Monserrat (Boris Karloff) has it in spades. It doesn’t matter that life has beaten him and his wife Estelle (Catherine Lacey) down and they’re living an impoverished life. The professor used to be a renowned hypnotist, employing his subtle skills to help rid patients of everything from anxiety to nicotine addiction. Things started going wrong after a muck-raking newspaper ran an expose, but he’s hung in there and kept trying to make life better for others.

Now he’s invented a machine that can not only hypnotize, but enable the hypnotizer to feel whatever the patient does. Marcus sees this breakthrough as a way to help old people, enabling (for example) infirm nursing home residents to have vicarious holidays. Estelle, however, wants to use the machine for a different purpose, a much more selfish and dangerous one…

Like a lot of horror flicks, The Sorcerers shows older folk preying on the young. However, it’s more intelligent than most and built on fascinating subject matter, one that directly taps into our love of power over others. It might also demonstrate how older folk routinely envy the young’s hedonistic opportunities, especially in swinging London.

The Monserrats pick up a bored clubber, Mike (Ian Ogilvy), and bring him back to their apartment. “For forty years I’ve been acclaimed as one of the world’s greatest hypnotists,” the professor tells him. Mike sarcastically claps and says “Bully for you, mate”, perfectly encapsulating the vague contempt the young so often have toward their elders. Undeterred, they offer “dazzling, indescribable experiences” and “ecstasy with no consequences,” but this is a straightforward fib. Poor Mike’s not gonna get anything of the sort, just a series of future blackouts.

It’s great to watch the downtrodden Monserrats come back to life by simply sitting at a dining room table feeling long-forgotten sensations as their plaything Mike takes an illicit nighttime dip in a hotel swimming pool with his posh French girlfriend or hammers along the highway on a stolen motorbike. Estelle, in particular, gets hooked on her virtual-reality drug, displaying a near-orgasmic excitement at being pseudo-young again. It’s all quite creepy, especially when Estelle starts enjoying the danger. “We all want to do things deep down inside ourselves,” she says, “things we can’t allow ourselves to do…”

Both Lacey and Karloff (in a late career renaissance that would include the remarkably prescient Targets a year later) put in good shifts. I like the way they convey old age as a growing sense of desiccation; of new experiences, respect from others, excitement, pleasure and hope all having dried up and long ago blown away.

Wunderkind director Michael Reeves, who went on to make the nasty as fuck Witchfinder General, does a good job in capturing dark impulses, bursts of horror and the groovy, mini-skirted vibe of the swinging sixties. Sadly, he never got to experience old age, or even middle age, dying in his mid-twenties.

Grandpa in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

Grandpa must be one of the feeblest fuckers ever put on film. According to his enthusiastic PR team (the slightly biased members of his family), he used to be the ‘best killer there ever was’, but now he’s such a dribbling spaz he doesn’t even have the strength to hold a hammer, let alone bash someone’s brains in.

We first meet the old coot being carried down the stairs by Leatherface and the Hitcher. He’s well-dressed and even looks a touch debonair, but his bald, bright white head does suggest something’s amiss, partly because it makes him resemble the senile older brother of Salem’s Lot’s chief vampire, Barlow. Grandpa’s also a bit spaced out. The Hitcher’s obviously a good grandson, though, and does his best to involve him. “Look, Grandpa!” he says, showing him a recently captured, trussed-up girl. “Look!”

Grandpa doesn’t perk up. Somehow I don’t think he’s gonna be the life and soul of the imminent blood-soaked party. To be honest, I believe this elderly gentleman would be better off placed under immediate medical supervision.

Meanwhile, Leatherface is patting his frail shoulders and kissing the top of his head, the only time he shows any affection in the entire movie (excluding that for his trusty chainsaw). Perhaps some sustenance would enable Grandpa to take a livelier part in proceedings. Leatherface cuts the girl’s finger and sticks the bleeding digit into the senior citizen’s mouth, causing her eyes to widen as he starts enthusiastically sucking. Suddenly both arms are off his lap and swaying with excitement. There’s life in the old dog yet!

It’s a false dawn. Later we see him slumped at the head of the dinner table. Just like Grampa Simpson, he seems to have nodded off at an inappropriate time. The boys put their heads together and decide it’s time to get rid of the female, perhaps tired of her near-constant screaming. Who better to do it than Grandpa? “Hey, Grandpa,” the Hitcher says, pointing at the thrashing girl, “we’re gonna let you have this one.”

As they move him in his chair toward her, the Cook reminisces about Grandpa’s legendary cattle-killing skills in the abattoir. “Why,” he soothingly tells the girl, “he never took more than one lick, they say. He did sixty in five minutes once. They say he coulda done more if the hook and pull gang coulda gotten the beefs outta the way faster.”

She’s then forced onto her knees with her head over a big metal bucket as Leatherface tries to get Grandpa to clasp a hammer. It keeps falling to the floor. I do believe this is Chainsaw’s attempt at levity.

“Come on, Grandpa,” the Hitcher urges, obviously disappointed at the dearth of head-splitting action. “Hit her! Hit that bitch!” The Cook is also doing his best with an impromptu cheerleader impersonation that involves clapping and jumping up and down. “Get her, Grandpa! Get her!”

It’s not happening though. The hammer’s in the bucket now. Leatherface fishes it out and uses Grandpa’s hand as a proxy, finally managing to draw some of the red stuff with a half-decent whack. Problem is, everyone knows it’s a cheat. Grandpa can suck blood, he might even be able to slurp, but killing? Don’t think so. He’s officially washed up. Oh, bloody hell, look what’s happened now. That crazed girl has just jumped clean through the window.

Sorry, grandpa, it’s off to the nursing home with you, good sir.

Lou in Atlantic City (1980)

Both Unforgiven’s The Schofield Kid and English Bob were memorable bullshitters, but I have a particular fondness for Burt Lancaster’s aging, ex-small-time gangster in Louis Malle’s fine drama.

Lou might dress well but he’s clearly past his prime, if he ever had one. Now he makes ends meet running the numbers in a decaying coastal city. Oh, he’s also a paid lackey for a demanding hypochondriac called Grace (Kate Reid), whose deceased gangster husband used to employ him. She’s not above needling Lou with taunts of ‘Mr. Ten Most Wanted’ and it’s easy to see he’s fighting a constant battle to hang onto his temper while dealing with her shrill, endless orders that include rubbing her feet and exercising her pampered poodle.

None of this fits in with his self-image, you see, the image he likes to project of having been an important face back in Las Vegas. Just look at the way his demeanor changes when he starts reminiscing about rackets, whores and guns with anyone dumb enough to listen. Suddenly he’s a man again, someone who knew the likes of Lucky Luciano, not some present-day downtrodden minion at the beck and call of a dried-up flower.

But are any of his tales true? Or was he actually a wannabe, a cowardly joke given the nickname ‘Numb Nuts’?

Whatever the case, it’s not long before he meets a loser who’s run off with a bag of Mob coke. A deal is hatched to regularly supply an illegal gambling den, enabling Lou’s yen for fantasy about the good old days to step up a gear. “Sometimes things would happen and I’d have to kill a few people,” he tells his new ‘partner’. “I’d feel bad for a while, but then I’d jump into the ocean, swim way out, come back in feeling nice and clean, and start all over again.”

Lou’s in the ascendancy. With a chunk of change in his pocket and the chance to consort with hoodlums again, the pictures in his head of who he is and the way he can go about doing things have magically aligned. Now he’s a man about town flashing the cash. Christ, he’s even found the confidence to stop perving on the gorgeous, dream-filled Sally (Susan Sarandon) and start wooing her with a nice bottle of wine at a fancy restaurant. And when she leans forward to say “Teach me stuff…” you can tell it’s music to his ears.

Of course, such a facade can’t last. Reality’s bound to intrude. Just look what happens when two hoods on the trail of the missing coke come calling, barely pausing for breath as they rough up both Lou and Sally on the street. In a few brain-scrambling seconds it’s laid bare he’s no tough guy, no commander of respect. Even Lou knows it, as evidenced by the marvelous prolonged close-up of his shaken face. His self-delusion has been dynamited in much the same manner as the rundown old hotels making way for the gambling-fuelled regeneration of Atlantic City. For perhaps the first time in decades this chivalrous, pathetic old fucker is standing on leveled ground.

So what’s Bugsy Siegel’s ex-cellmate gonna do?

Hobson in Arthur (1981)

Can you imagine having a butler or valet?

I can’t, even though I’m the laziest bastard on the planet. It’s just beyond me how some people pay a dogsbody to run a bath or fetch an umbrella or open the front door. I guess it’s all to do with subtly demonstrating wealth and power, but I’d be embarrassed to ask an employee to do such mundane and trivial tasks. After all, what are mothers for?

The duty-obsessed Stevens in The Remains of the Day would have to be my favorite cinematic butler, but Arthur’s acid-tongued Hobson (John Gielgud) is a close second. Hobson surely has one of the highest hit rates for quality lines given to any supporting character in movie history. Nearly everything that pops out of his erudite, disapproving and occasionally vulgar mouth is funny or on the money. Listen to his putdown of the shoplifting, garishly dressed Linda (Liza Minnelli) after watching her cause a kerfuffle on a Manhattan street: “Usually one must go to a bowling alley to meet a woman of your stature.” And his elegant parting jab? “Good luck in prison.” It’s this constant flow of bon mots, and the way they’re couched in such wonderfully deceptive politeness, that makes the ultra-sarcastic Hobson such a treat.

Introduced standing ramrod straight holding a breakfast tray as the elevator doors open into Arthur’s sumptuous bedroom, it’s not hard to tell he’s a prim and proper English gentleman of the finest pedigree. “Please stop that!” he barks upon seeing his playboy employer cuddling a floozy in bed. “Hi,” she groggily manages through a hangover, prompting Hobson’s best lemon face. “You obviously have a wonderful economy with words,” he replies. “I look forward to your next syllable with great eagerness.”

Arthur (Dudley Moore) is, of course, the son Hobson never had. For decades he’s been trying to get the ‘spoiled little bastard’ to grow up, but hasn’t made much progress since the days of playing hide and seek. Now he treats Arthur like an overgrown child, routinely telling him to sit up straight or not to forget to wash his armpits while promising ice cream if he accomplishes anything of the mildest importance. Not that the immature Arthur ever stays on track for very long, mainly because he’s a bored pisshead. Still, the impeccably dressed Hobson isn’t beyond giving Arthur some home truths or doling out a backhander whenever his patience runs out.

But underneath it all there’s deep affection. Mind you, who cares about that soppy shit? Much better to dwell on the guy’s seemingly endless sarcasm, such as when Arthur states he’s going to have a bath.

“I’ll alert the media,” comes the ever-courteous reply.

Buck Grotowski in Monster’s Ball (2003)

Racism is an interesting subject to explore, especially if done with verve and imagination as Blazing Saddles and Planet of the Apes managed. However, one of my pet hates is a movie that shows a character learning Racism Is Wrong before abruptly turning over a new leaf. Take Maggie Smith’s character in 2011’s god-awful Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. She’s an elderly bigot that travels from London to India for a cheap hip operation. A fair chunk of the time she’s spewing hate, banging on about Indians with their ‘brown faces and black hearts, reeking of curry’. Of course, such an attitude does beg the question of why she’s placing her health in the care of these people in the first place, but by the end of this thoroughly unrecommended flick she’s done a one-eighty. Those brown-skinned chaps are apparently all right after all.

Fuck, I hate such a facile handling of a complex, uncomfortable subject.

Racism is a pretty damn difficult ailment to rid yourself of, especially if it’s been drilled in from a young age, and most racists never accomplish it. Instead they learn to manage it, to try not to act on it or to keep it hidden, mainly because they know there can be serious consequences for any outbreak. They’re still prejudiced; they just don’t show it. Like alcoholism, the malady sits within, perhaps suppressed, perhaps cowed, but always biding its time.

So, yeah, I find any movie with an about-face approach to racism trite. I much prefer flicks that show racism to be self-defeating. This is where Monster’s Ball scores big. Back at the turn of the century this capital punishment-flavored drama caused a splash, mainly due to Halle Berry’s energetic sex scene (“Make me feel good!”) and the fact she went on to become the first black woman to nab a Best Actress Oscar. Well, I’m not gonna complain about her nudey gyrating, but I will say Monster’s Ball is weakened by its substantial implausibilities.

However, the one thing it does get right is Peter Boyle’s contribution. Thirty-three years after his hateful turn as a bigoted everyman in the sleeper hit Joe, he’s back playing a mean sonnuva bitch by the name of Buck. In Joe he started by ranting about blacks while sitting in a bar. He does the same here sitting at a window after spotting two ‘porch monkeys’ cutting across his rural Georgian property.

“There was a time when they knew their place,” he tells his equally fucked-up son, Hank (Billy Bob Thornton). “Wasn’t any of this mixing going on.”

Right, we’ve got the measure of this unsmiling patriarch, a man who probably couldn’t even spell ‘Southern hospitality’ let alone practice it. Now it’s just a case of how far he’s gonna push things. Quite far as it happens. In his best scene Hank’s new girlfriend Leticia (Berry) comes calling with the gift of a hat only to find Buck alone in the house. Buck pesters her for a ciggy, slips on the headwear and makes some complimentary remarks about its quality. Is the old fucker softening? And then he fixes her with a dead stare. “In my prime,” he says, “I had a thing for nigger juice myself. Hank just like his daddy. Ain’t a man till you split dark oak.”

Buck, of course, is unapologetic when Hank discovers he’s been up to his old tricks. “I’m your father,” he says, as if he’s being disgraced. “Remember that.”

But his little faux pas proves to be the straw that breaks the camel’s back. This poisoned oak tree, whose wife and grandson both ‘failed’ him by committing suicide, is condemned to live the rest of his barren life in a nursing home.

Alone, disorientated, and still devoid of any insight into his lifelong curse, we leave him sitting on an unfamiliar bed staring into space.

Harry Brown in Harry Brown (2009)

Art’s a strange old thing.

As we know, there’s nothing new under the sun. Nothing illustrates such an adage better than a vigilante flick like Harry Brown. Christ, this shit has been done so many times beforehand it’s almost funny. Do I really need to tell you Michael Caine plays a decent, ex-army guy trying to keep out of the way of the ever-growing scum clogging up his little corner of the world? I mean, is it any surprise the cops are useless and his bullied, terrified best mate gets splatted? You know what happens next, yeah? I guess the ‘twist’ here is that Harry’s an emphysemic, widowed pensioner. A sheep in sheep’s clothing.

C’mon, this is about as stale and silly as it gets, right?

Well, no, not exactly.

Like I said, art’s a strange old thing. I guess it’s all about the way you do it. Harry Brown has an undeniably tired plot (in which the dots can be joined by a retarded child) but it still manages to work. In fact, it’s an entertaining, surprisingly nasty watch. Events unfold with a pleasing economy, typified by its chaotic opening that covers gang initiation, drugs, profanity, mindless machismo, an inadvertent killing and a motorbike crash in two minutes flat. All the visceral confrontations, fights, shootouts and killings are well-handled. The hoodie-clad gang members fizz with a sour energy and are convincingly skuzzy, especially in the police interview room with their obscene sexual threats. They live on the usual rundown council estate, only this one’s situated next to a motorway. To say the place is lacking in charm and community spirit is somewhat of an understatement, although it does provide nightly entertainment. Who needs HBO when you can look out the window to see law-abiding citizens getting beaten up?

Caine wanders through this urban shittiness in quite a subdued way. I’m not even sure he ever raises his voice. He certainly doesn’t rant about reclaiming the streets for decent folk or start trotting out the quips once his hands get bloody. He might put a couple of toes on a soapbox at one point but he soon removes them. However, I like the way he reveals his inner steel in a plausible, unhurried way. Thank God we don’t get any obvious stunt doubles or age-defying, plausibility-undermining bouts of strength and speed. Indeed, at one point he pursues a baddie only to collapse from exhaustion and end up in hospital.

Caine has made a lot of movies and I doubt he’s given them all one hundred per cent, but you can tell the old fucker’s into this one. Best of all is his electrifying confrontation with a bare-chested Sean Harris in a hideously unpleasant drug den. With his badly self-drawn tattoos, heroin habit, indifference to human suffering and fondness for making rape videos, I reckon even scabies would think twice about hanging around with this dude. Caine’s mildly bewildered expression at someone choosing to live in such a manner is priceless.

In short, Harry Brown might be a warmed-up rehash but it still succeeds with its credible portrayal of a none-too-sprightly vigilante. Funnily enough, it’s the youthful, ultra-polite Emily Mortimer respectfully on Caine’s trail of mayhem who hits the movie’s only bum note. She has to be Britain’s least convincing detective-inspector.

Zev Guttman in Remember (2015)

We all have regrets. We all imagine a different past from time to time. Some of us probably even fantasize about being someone else. Hell, I’m certainly guilty of wondering what it’d be like to be Raquel Welch wandering around a prehistoric landscape in a fur bikini. Perhaps one day we’ll invent machines or come up with a drug that’ll enable us to do things like that at the drop of a hat.

In the meantime, we’ve got nature’s sly old beast, dementia, and its supremely fucked-up older brother, Alzheimer’s. These two afflictions usually get the worst of raps but they do provide ample opportunity for mental escape. A nice little break from that big boo-hoo called reality. Who knows what horrible shit its lucky recipients are erasing? Who knows where they’re popping off to?

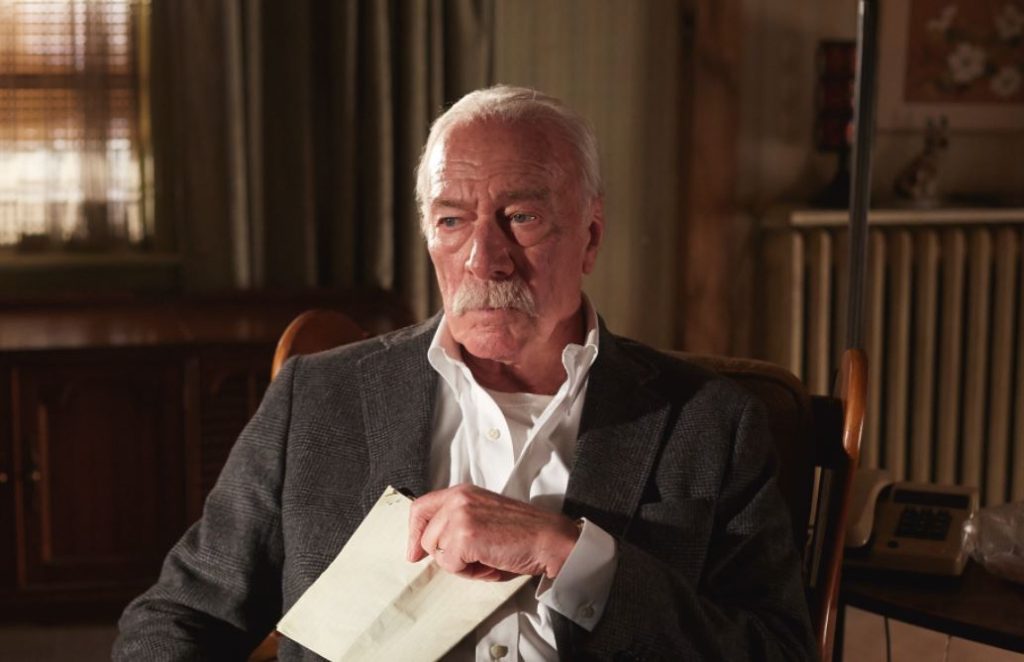

Take my mum’s favorite, Christopher Plummer, in Remember. This guy’s so out of it he keeps forgetting his wife’s no longer alive. One minute he’s married, the next he’s a footloose and fancy-free widower. He can be cognizant, then take a nap and (just like me after two whole pints of beer) have no idea where he is or what he’s doing. Never mind, a fellow Jew in his nursing home has just given him a letter, a letter that provides instruction for tracking down and killing a former Auschwitz guard who murdered both their families.

And so our elderly, gun-wielding assassin starts putting one doddery foot in front of the other. It’s a fascinating odyssey in which he’s mainly able to remember his deadly mission but often gets lost in a thick fog of confusion. Every unpredictable encounter with receptionists, taxi drivers, customs officials, security guards, fellow passengers and especially Breaking Bad’s Dean Norris is so well done that the flick never loses momentum, despite its protagonist only being able to move at a quarter of a mile an hour.

It’s marvelous, Nazi-tinged stuff, both a vivid depiction of a failing brain and the way in which monstrous evil is capable of creating ripples that can keep traveling outwards for decades.