Some movies are way ahead of their time.

Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom is a good example, a voyeuristic horror pic centering on a serial killer filming his victims’ last moments while stabbing them through the throat.

People just weren’t ready for that kind of sicko shit in 1960, the revulsion apparently resulting in the revered director’s career being ruined. Hitchcock put out a similarly fucked-up psycho-sexual slasher the same year, perhaps benefitting from having the good sense not to capture all the murderous perversion in garish Technicolor.

Them’s the breaks.

And then there’s Never Take Sweets, admittedly less in your face than Peeping Tom and Psycho, but still tackling the icky subject of pedophilia head on.

The present hysteria surrounding kiddy fiddlers probably dates from around the mid-80s. Now I grew up in this decade when kids still walked to school and that Stranger-Danger stuff was barely trotted out. I played with my mates all day long over the park, by the river and on waste ground. No one bothered us, except the bigger boys wanting to steal our football or push us around. In fact, I can’t recall anyone from my 1200-strong school telling a story about ever having to deal with a nonce, a flasher or a weirdo.

Well, times have changed and parents today appear convinced there are pedos (the Satanic sort, the murderous kind and the more commonplace type) loitering everywhere whereas the threat is much more likely to emanate from within the family. My 10-year stint as a court reporter underlined this unpalatable fact and I can still recall staring at a defendant accused of giving his two-year-old daughter genital warts. Pedos exist, all right, but they’re much more likely to be an uncle, a cousin or a granddad rather than some nonce hanging round a park bench. Oh, and I’ll concede they gravitate toward institutions, such as the Catholic Church.

Our exaggerated fear of pedos (and our terror of having such a character-ruining accusation anywhere near us) has led to blokes like me routinely pretending children don’t exist while teachers have become wary of being in the same room as a solitary student. Sadly, some fathers even get nervous about bathing their toddler daughters. It’s a daft state of affairs, but if you want to see such media-induced panic brilliantly satirized I suggest you watch a tiny clip of that arch prankster Chris Morris strutting his fantastic stuff here.

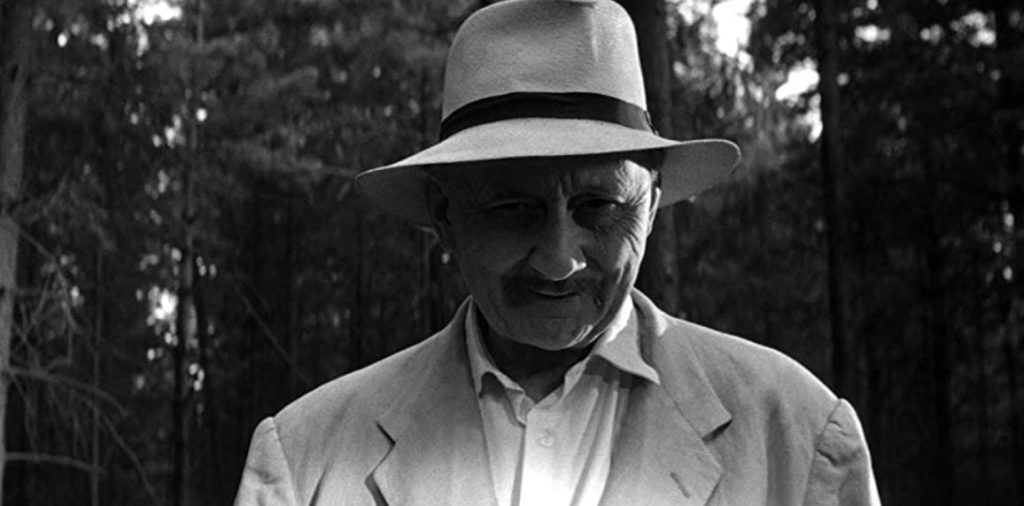

Anyhow, back to Never Take Sweets. This 81-minute flick might have sunk without a trace upon release but Hammer still came up with a gem. Honestly, this is an uncompromising, seriously creepy bit of cinema. It begins with two little giggling girls playing on a swing. Unbeknown to them, an old man with trembling hands is spying on them through binoculars from a nearby house’s upper bedroom window.

After losing her candy money in the long grass, Jean (Faye) is upset, but her friend Lucille (Green) simply looks at the house and announces: “I know somewhere where we can get some candy for nothing.”

Later at home Jean complains of a nail wound on her foot, leading her parents to ask why she was barefoot in someone’s house.

“We took all our clothes off,” she cheerily says. There’s a pause and the wonderfully blithe follow-up question: “Wasn’t that right?”

From here things snowball in an increasingly unsettling manner as it’s revealed the old man is none other than Clarence Olderberry (Aylmer), the doyen of the wealthiest family in the small Canadian town.

Uh-oh.

The child’s grandmother immediately warns against pursuing police action. “We don’t want the whole town to know,” she says. “You must keep a sense of proportion. After all, Jean wasn’t hurt.”

However, after Jean suffers a nightmare that the old man is after her, the outraged British father Peter Carter (Allen), who has just been appointed the town’s high school principal, decides to launch a prosecution.

However, the pathetic, piss-weak police captain says although the ‘old man got a little fresh with those kids’ no real harm has been done.

“You and your husband are strangers in this town,” he tells the mother. “No one knows much about you… High school principals come and go but the Olderberries, you might say, go on forever.”

Then we get excerpts of small-town gossip, essentially blaming the children for going to the house on their own accord, as well as neighbors shunning Jean. This is a well-directed, believable and queasy movie, perfectly demonstrating how attitudes and practices toward child abuse needed to change.

Performances are uniformly excellent. Special mention must go to Faye, whose chatty lack of comprehension is quite disconcerting, and the corrupt, intimidating younger Olderberry, played by Bill Nagy. “You lousy outsiders,” he shouts at the father. “You come here without knowing a soul looking for a job, we find you one, and the first thing you do is stir up trouble.” He then threatens to put the little girl on the stand and get his lawyers to ‘tear her apart.’

There’s so much to like here, such as a superbly handled trial with a detestable defense lawyer, a near-wordless bogeyman in the form of the possibly senile old man, Freddie Francis’s gleaming black and white cinematography, and a gripping final descent into horror.

You won’t forget the rowing boat scene in a hurry.