Woody Allen is a prolific artist who’s been making roughly a film a year since the late sixties. His timid yet talkative onscreen persona (simultaneously intellectual and stupid, riddled with self-doubt and wrapped up in his weedy, balding, bespectacled frame) surely places him among the most distinctive film stars of all time. It’s a double-edged sword in that some people love his neurotic, instantly recognizable schtick while others loathe Allen on sight. I find later stuff like Mighty Aphrodite, Small Time Crooks, Jade Scorpion and Vicky Cristina Barcelona underwhelming, but I’ll always stick up for his career’s splendid first phase, especially whenever one of his scrawny alter egos starts boasting about having ‘the coiled sexual power of a jungle cat.’

Take the Money and Run (1969)

Allen’s directorial debut takes the form of a mockumentary detailing the life of inept career criminal, Virgil Starkwell, who tries his hand at everything from pool hustling to bank robbery. Apart from setting it in San Francisco rather than his beloved New York, the staples of Allen’s future movies are all here: the fondness for mixing up absurdity and farce with more sophisticated, intellectual humor; his Jewishness; the jibes at God, religion and psychiatry; the mocking of machismo and criminal tendencies; the jazz score; the running gags; the portrayal of a dysfunctional childhood complete with disapproving, bickering parents; and his preposterous ability to snag beautiful women, despite being a combination of runt, loser and klutz (“I don’t know how to act with girls… I have a tendency to dribble.”) Perhaps the only obsession missing is the reverence for art.

Money is a plotless, rapid-fire gag fest complete with voiceover, talking heads and ham-fisted cello playing. Not all of it works, but it does have a high chuckle factor as Virgil teams up with criminals who have been convicted of such appalling crimes as dancing with a mailman and marrying a horse. There’s an excellent chain gang sequence in which he only gets one hot meal a day (a bowl of steam) and ends up locked in a sweatbox with an insurance salesman. This is an easygoing, undemanding watch that remains endearingly silly.

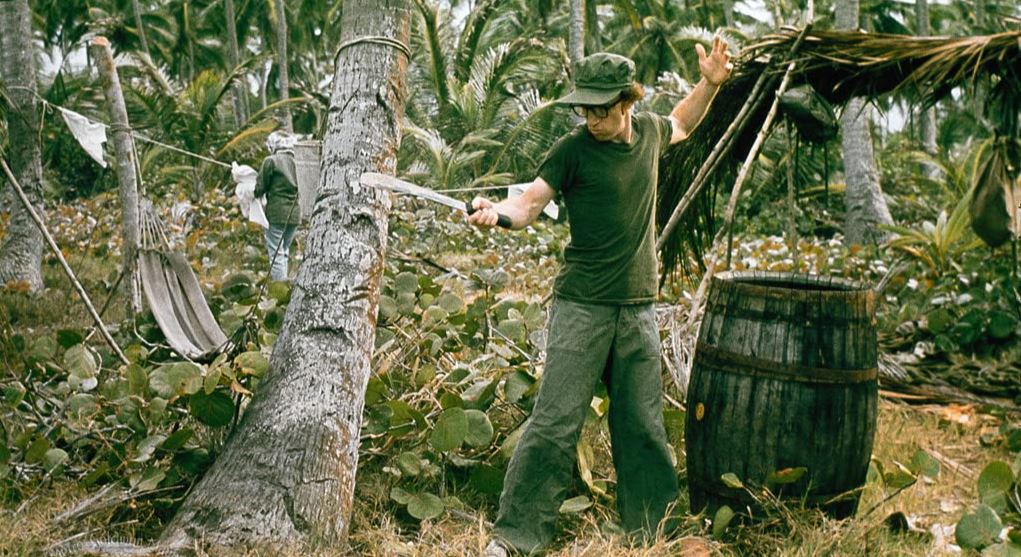

Bananas (1971)

An all right opening half-hour in New York with a couple of excellent bits of physical comedy gives way to a pretty flat forty minutes in a fictional South American country. Sure, there are some nice jabs about the cyclical nature of political violence, American foreign policy and politics in general (“Let me be vice-president, that’s a real idiot’s job”), but it still feels more like extended sketch comedy than a well-rounded plot. However, I did enjoy an early Sly Stallone appearance as a leather-clad mugger on a train, as well as a TV newsreader solemnly telling us: “The NRA declares death a good thing.” Plus, it’s hard not to wince when Woody tries to justify buying porn in a corner store to another customer: “I’m doing a sociological study on perversion. I’m up to Advanced Child Molesting.”

Play It Again, Sam (1972)

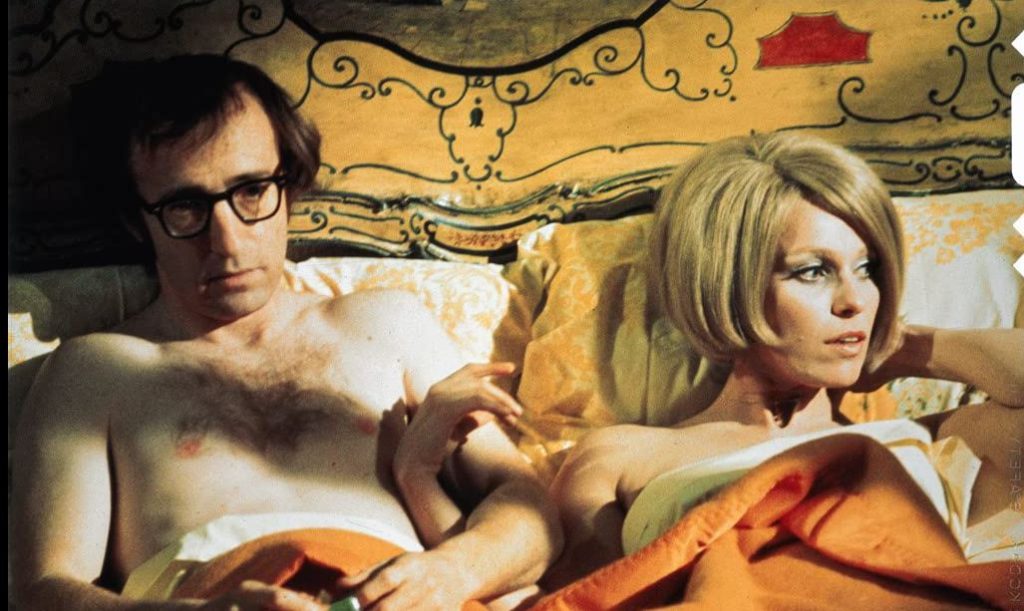

Sam is my pick of Allen’s early ‘funny’ stuff, an inspired and consistently amusing odyssey through the nightmare of post-marriage dating. Allen is Allan Felix, a ridiculously immature hypochondriac film critic who’s depressed at the collapse of his two-year-old marriage. Somehow his wife’s desire for greener pastures comes as a shock, even though she kept flicking through the TV channels during sex and wants out on the grounds of ‘insufficient laughter.’

“Why can’t I be cool?” Felix wonders aloud. “What’s the secret?” Perhaps not endlessly watching movies while sucking on frozen TV dinners, mate. His married friends, Dick and Linda Christie (Tony Roberts and Diane Keaton), decide to help but fixing the chronically repressed and self-conscious Felix up with an attractive and well-adjusted female is not easy. Luckily, an apparition of Humphrey Bogart (Jerry Lacy) is along for the ride to give him those crucial, confidence-boosting tips. “Dames are simple,” he tells Felix in his typically no-nonsense way. “I never met one that didn’t understand a slap in the mouth or a slug from a 45.” But Felix is the polar opposite of Bogey, immediately passing out from his first sip of bourbon and soda in a bar.

What follows is a series of disastrous dates with blowhard nymphos and suicidal nihilists. They involve our clumsy, breast-obsessed hero doing everything from drinking aftershave and knocking things over to pretentiousness and dance floor cock-ups, all while trying to practice ‘tremendous poise’. Sam is brilliant at satirizing the absurd lengths (read: exaggerations and outright lies) that many of us employ while trying impress the opposite sex, especially when it comes to grooming, lifestyle and accomplishments. Despite its thin subject matter and liberal sprinkling of monologues, flashbacks and fantasy sequences, this Casablanca homage has a lovely, organic feel. There are so many fantastic one-liners (“They said they were hairdressers”) that you even occasionally stop getting distracted by Keaton’s hideous dress sense.

Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex (1972)

Not sure I’ve ever seen a good anthology. The approach might work for books, but film…? Believe me, I’ve tried with all those cheesy horror anthologies that kept popping up through the seventies and eighties like Asylum, The House That Dripped Blood, Tales from the Crypt, Creepshow, and of course, that feline fiasco The Uncanny. Allen’s big hit Everything, the tenth highest grossing movie of 72, is a good example of how tantalizing but ultimately unsatisfying the format can be. Many fans put this one down as a dated, uneven collection, unable to agree on which sketches work.

At least it starts well with its opening Cole Porter song Let’s Misbehave piped over shots of frolicking rabbits. Allen kicks things off playing a Hamlet-spouting medieval jester, who’s desperate to get his hands on the queen’s jealously guarded fleshy jewels. Regrettably, his humble status and unappreciated court act mean he hasn’t got a chance in hell. What’s a horny fool to do?

Cheat, of course, by slipping a prescription-free aphrodisiac into the queen’s drink. What follows is a master class in ridiculousness as Allen is thwarted by her chastity belt. “I must think of something quickly,” he says, “because before you know it the Renaissance will be here and we’ll all be painting.” Full marks, too, for Anthony Quale’s irked turn as the stern king.

However, Allen fires off his best shot during the second segment about bestiality. It’s an adroit exercise in economical storytelling that’s both hilarious and poignant. Gene Wilder plays a respectable, but slightly bored doctor, caught off guard during a routine consultation when a patient confesses an overwhelming love for a sheep named Daisy. “It was the greatest lay I ever had,” the man insists as Wilder treats us to a lengthy array of facial reactions. Unfortunately, the road to true love never runs smooth and the lovelorn patient wants Wilder to examine his ‘girlfriend’ as she’s grown ‘cold’ and ‘indifferent’ during their lovemaking. “I’m an MD, not a veterinarian,” Wilder replies. “It’s not normal to experience mature love for anything with four legs.” It’s all played so wonderfully straight-faced, resulting in one of the greatest skits I’ve ever seen. Wilder’s performance is comic perfection.

Everything then tails off with four duds in a row until it finds a fitting, ahem, climax. It has to be said that even trying to illustrate what the hell goes on during ejaculation is inspired in itself, but the fact Allen comes up with such an unforgettable sketch is testament to his potent imagination. He depicts each part of the body as being controlled by a group of scientists in the brain who pass on orders to the manual workers elsewhere. In a memorably absurd role, Allen plays an anxious paratrooper sperm. “I’m scared, I don’t wanna go,” he tells his much more confident fellow sperm as they prepare to launch. “Who knows what it’s gonna be like out there? You hear these strange stories, like sometimes the guys will slam their heads up against a wall of hard rubber. Or what if it’s a homosexual encounter?”

Sleeper (1973)

Allen’s second collaboration with Keaton sees him play a cryogenically frozen patient brought back to life in 2173. Now a 237-year-old former health store owner, he’s none too pleased upon being told what’s happened: “I can’t believe this! My doctor said I’d be up on my feet again after five days. He was off by 199 years!”

New York has become a police state and he’s quickly declared a rebel, but at least the natives are just as screwed up as ever. “Sex is different today,” the highly strung Keaton tells him. “We don’t have any problems. Everyone’s frigid.”

Sleeper is an eighty-five-minute exercise in goofiness, managing to fit in everything from gags about Richard Nixon and Miss Universe to a lot of Buster Keaton-inspired slapstick and a Blanche DuBois impersonation. It has deliberately cheap effects, such as the plastic-covered cars, the robots that are merely people acting robotically, and the fact Allen’s cryogenic freezing involves little more than encasing him in silver foil (while still wearing his trademark glasses).

I’ve always enjoyed the nose-stealing loopiness of Sleeper, especially Allen’s clothes-shredding introductory use of the orgasmatron, its many nods to other sci-fi flicks, and its solitary NRA dig, this time describing it as ‘a group that helped criminals get guns so they could shoot citizens’.

Depressingly, Allen depicts McDonald’s still going strong in 2173.

Love and Death (1975)

This eighty-minute existentialist comedy is perhaps Allen’s best demonstration of his cowardly, anti-machismo persona (“You’re scared? I’m growing a beak and feathers”). He plays Boris, a 19th century Russian scholar who gets dragged into the Napoleonic Wars. Of course, he’d rather stay at home and write poetry on the basis that he ‘can’t shower with other men’. When forced to go by his family, he sets off clutching his framed butterfly collection. It’s not long before he messes up at boot camp, experiences battlefield slaughter and fights a duel, somehow managing to not only survive but become a hero.

Boris struggles to believe in God (“You think I was made in God’s image? Take a look at me. You think he wears glasses?”), sees nature as an ‘enormous restaurant’, occasionally talks to Death, and is in love with a promiscuous cousin. There’s a lot of silly stuff here, although its comedy is underpinned by a more intellectual flavor and occasional sophisticated word play that riffs on Russian literature.

Many see Love and Death as the bridge between Allen’s knockabout stuff and his more mature comedy. It’s a decent, gently amusing watch boasting some excellent one-liners and a pastry-obsessed Napoleon. Plus, if you’re being tormented by an existential crisis and/or suicidal thoughts it magically offers the solution. “I have lived many years,” an elderly holy man declares. “After many trials and tribulations, I have come to the conclusion that the best thing is blonde twelve-year-old girls. Two of them wherever possible.”

The Front (1976)

If you’re not too keen on Allen, I suggest taking a look at this one as it might help you change your mind. There’s no knockabout, neurotic, madcap stuff here, probably because he neither wrote nor directed The Front. This quirk in his career resulted in a dialed down persona that immediately feels different.

The Front is a funny yet melancholy drama that captures the pain and sheer nonsense of McCarthy-era New York. It opens with a lovely, black and white Sinatra-accompanied montage of 50s America before we meet Allen. He plays the ‘practically illiterate’ Howard Prince and from the offset it’s clear he’s not a morally upright, leading citizen. In fact, he’s a self-centered, ass-grabbing, vaguely dishonest small-time bookie forever telling people stories.

When a blacklisted writer friend asks him to ‘front’ by submitting scripts under his name to a TV studio, this bullshitting weasel jumps at the chance of earning a ten per cent commission. Suddenly Howard’s got a regular income for pretty much doing nothing, his social standing is boosted, and he even starts seeing a pretty producer. She thinks he’s ‘genuinely modest’ because he doesn’t want to talk about his work whereas the truth is he hasn’t read a word of the acclaimed scripts that bear his name. Soon he wants to front for extra writers on the basis it doesn’t involve any more work and will triple his unearned income. At least the first writer he’s feeding off has his number. “I know you, Howard,” he says. “You’re gonna take off and fly right up your own ass.”

Meanwhile, Hecky Brown (Zero Mostel) is a talented entertainer whose unfortunate flirtation with Communism is rapidly eroding a successful career. “We’re in a war against a ruthless and tricky enemy who will stop at nothing to destroy our way of life,” he’s told by an anti-Communist official, a quietly frightening zealot who wants Hecky to inform and spy on other suspected sympathizers. Hecky holds out, but it results in this proud family man barely being able to snag a day’s work and his fee dropping from five grand to $250. With his hangdog face, Mostel paints a heartbreaking portrait of a shunned artist being pushed into quicksand. “Talent has no protection,” he says. “You do as they say or else.”

The Front is not a particularly well-known comedy-drama, but it features a pitch perfect supporting cast while offering a terrific insight into writing, delusion, witch hunts, show trials, ostracism, power and professional relationships.

Annie Hall (1977)

This is the one in which Allen the successful artist made a gigantic leap into the mainstream, robbing Star Wars of Oscar glory in the process.

Not that he did anything different. I guess it was a case of paying his dues, building his audience and letting momentum do the rest. Annie Hall is certainly calmer and more mature with no clowning or slapstick, but it still contains Allen’s familiar collaborators, the same settings and his fondness for direct to camera stuff, inner monologues and surrealism. All right, the cartoon interlude, the Bob Dylan jibes and the withering rejection of LA are new.

Its plot is tiny, centering on the dissection of a relationship between Alvy Singer (Allen) and the titular character (Diane Keaton, up to her old sartorial missteps). We see the initial meeting, the tentative attempts to move things onto a romantic level, the satisfying sex, the camaraderie, the insecurities, the minor arguments, the big decisions like moving in together, the jealousies, the sexual problems, the semi-breakups and the good-natured dissolution. For the most part they share a simple, relaxed love built upon an intellectual, emotional and physical connection.

But it doesn’t last, bemusing the already insecure Alvy: “A relationship is like a shark. It has to constantly move forward or it dies. And I think what we got on our hands is a dead shark.”

Now in his over-analytical way he has to try to work out why he’s failed again. This involves examining everything from his rollercoaster-afflicted childhood and past marriages to his obsession with death and listening to a whacky Christopher Walken.

Ultimately, there’s a lot to enjoy about Annie Hall, but it does start to stagnate during its final half an hour. I don’t find it as funny as something like Play It Again, Sam. Perhaps that’s because its long-winded attempt to illustrate the ins and outs of relationship failure is occasionally punctured by a pithy piece of wisdom, such as when a passerby tells Alvy: “Love fades.”

Yep. It really can be that simple.

Manhattan (1979)

Many of Allen’s movies focus on a protagonist being terrified of women and screwing up to an absurd degree whenever near them. Or as Allan Felix says in Play It Again, Sam: “I have a tendency to reject before I get rejected. That way I save a lot of time and money.” Yet it’s noticeable that Allen’s immature heroes not only get plenty of girls but bloody good-looking ones, too. There must be something in this neurotic funnyman schtick that females can’t resist, leaving me to wonder who gets laid the most: Allen’s characters or James Bond.

In the beautifully shot, black and white Manhattan, Isaac Davis (Allen) is involved with a 17-year-old cracker (an excellent Mariel Hemingway), despite the fact he’s forty-two. “I’m dating a girl who does homework,” he tells his friends. Isaac is the usual angst-ridden disaster with two failed marriages behind him. He’s also quit his TV writing job in a fit of pique.

The best thing in his life is Tracy (Hemingway), the epitome of simple, grounded sweetness. They have a great, relaxed time together. She’s in love, but he won’t take anything she says seriously, let alone accept such genuine emotion. “You’re a kid and I never want you to forget that,” he says. “You’re gonna meet a lot of terrific men in your life. I want you to enjoy me, you know, my wry sense of humor and astonishing sexual technique, but never forget that you’ve got your whole life ahead of you… Think of me as a detour on the highway of life.”

Isaac instead gets involved with the uptight Mary Wilkie (Diane Keaton in thankfully less atrocious clothing). She’s representative of the pretentious, unbearably opinionated, artsy-fartsy crowd that Isaac hangs around with (“I finally had an orgasm,” one such member tells him, “but my doctor told me it was the wrong kind.”) Of course, it’s a doomed relationship, making Isaac realize that the honest, uncomplicated, life-affirming Tracy was the one after all.

Perhaps her extreme youth is the only new ground Manhattan breaks because otherwise it’s Allen’s typical assortment of intellectualism, relationship stuff, pseudo-intellectualism, affairs and over-analytical fretting. Watching one Allen movie after another does make it clear how he likes to cover the same ground because he sure as hell shuns action and big plots. This may make it sound like I’m not a fan of the Gershwin-accompanied Manhattan, but it’s probably just a case of mild Allen fatigue.

Like Annie Hall, Manhattan is free of knockabout comedy and just as talky. Still, it’s a good standalone film and proved to be another box office winner. Towards its end, it starts hitting its straps as Isaac lies on a sofa listing all the stuff that makes life worth living, such as Groucho Marx, the second movement of the Jupiter Symphony, Marlon Brando and Tracy’s face. From here it’s a lovely, eight-minute stroll to one of the most beautifully straightforward closing lines in cinema.

Zelig (1983)

Both a well-rounded oddity in Allen’s early catalog and a technically accomplished groundbreaker, this one gives us an intriguing documentary-style account of a man who can assume the physical characteristics of others. It’s a long way from being laugh out loud funny, but at least it’s not another wallow in relationship angst.

Allen is Leonard Zelig, a man in the 1920s whose terrible childhood has resulted in him becoming a mental cripple without self-esteem. Now he has a chameleon-like ability to copy whomever he’s standing alongside, whether they’re black, Chinese, overweight or a National Socialist.

Doctors are unable to agree on a diagnosis with some thinking it’s glandular or a brain tumor. Others put it down to eating too much Mexican food. It’s only when a kindly, dedicated female doctor takes him under her wing that the reason is revealed. “It’s safe to be like the others,” he confesses under hypnosis. “I wanna be liked.”

Christ, have you ever heard anything so sad?

Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989)

Crimes has a dark, unsettling center. It quietly lays bare chilling truths and can only help undermine the idiotic belief in karma, if not God himself. Don’t go thinking it’s a depressing immersion in futility, though. Despite a clear-sighted view of reality and human behavior, it’s so superbly written that it still manages to offer a life-affirming thread of hope.

Judah Rosenthal (the Oscar-winning Martin Landau) is an upper-class, married father of two and successful ophthalmologist. He’s also ensnared in a Fatal Attraction-style affair with a woman who’s not only a hair’s breadth away from telling his oblivious wife, but threatening to expose an earlier bout of embezzlement. She can’t be bought off and won’t listen to reason, insisting: “I won’t be tossed out.”

But what’s a pillar of the community like Judah to do? He hates getting his hands dirty, even though it’s clear at the very least he’s a rank hypocrite. As a child it was drilled into him that the ‘eyes of God are on us always’ yet now he’s faced with the ultimate choice: self-preservation (“God is a luxury I can’t afford”) or the risk of losing everything (“My life’s about to go up in smoke!”)

Judah is also treating a Rabbi patient, whose sight is rapidly ebbing away. He’s a humble, decent guy that believes in a ‘moral structure’ to the universe despite his steady descent into literal darkness. He urges Judah to confess his longtime infidelity, suggesting there might be unforeseen benefits.

Elsewhere, Clifford Stern (Allen, now looking like a bespectacled cross between Stan Laurel and C-3PO) is a small-time, unemployed documentary-maker trapped in an unhappy marriage. His brother-in-law Lester (a funny Alan Alda) happens to be a successful, award-winning TV producer, but he’s also an insufferable, pompous ass. Lester (at his wife’s behest) gives Clifford a job to make a short film celebrating his achievements. Allen falls for an associate producer on the project, but his eyes are open about his chances of success both in his love life and career. “As you go through life, great depth and smoldering sensuality do not always win,” he says.

Allen has long joked about the coldness of the universe, the absence of God and the meaninglessness of life. Take Annie Hall’s Alvy Singer outlining his somewhat bleak take on things: “I feel that life is divided up into the horrible and the miserable. Those are the two categories. The horrible would be like terminal cases. Blind people. Cripples. I don’t know how they get through life. It’s amazing to me. And the miserable is everyone else. So when you go through life you should be thankful to be miserable.”

In Crimes, Allen discards the flippancy and instead examines existentialist questions at length. He depicts a world in which worthwhile men commit suicide or are otherwise blighted; facile wankers prosper; genuine emotions go unrequited; the talented never find a platform; the corrupt and wicked are not brought to justice; and your own sister can go out on a date only to end up tied to a bed with a freshly laid turd on her chest.

How to navigate through such murk? Crimes shows us that some people believe in nothing and do whatever is necessary, giving a dark deed no more thought than pushing a button. Some think there is a moral framework to existence, regardless of religion. A persistent handful insists that the world is a cesspit without God. Others stick their head in the sand, ignoring the appalling lows of human history while admitting the idea of God is preferable to taking on board a more believable truth. Perhaps the stoic Rabbi with the failing eyesight has the answer: “Sometimes to have a little luck is the best plan.”

Crimes was Allen’s fourth drama and perhaps an excellent place to start if you struggle to grasp the man’s appeal. His character Clifford essentially provides humor, but by now Allen has learned the power of restraint and there’s no clowning. Crimes is a minor triumph, especially the way its Shakespearean quality puts such an emphasis on eyes, God, conscience, justice and, of course, the heart.

By this point Allen had been making movies for two decades, netting a boatload of Oscar nods for his relentless output. There had certainly been wobbles (the forgettable Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, the unconvincing Purple Rose of Cairo), but Crimes illustrated there was still plenty of creative and insightful life left in the old dog.

Sorry, vicious jungle beast.