126 Minutes, PG-13 for multiple airplane crashes

Fair Value of Kaze Tachinu: $45.00. It’s Miyazaki’s most mature and introspective film. It’s not a film for every child, but it’s the film to show if you want your kids to dream of being engineers instead of princesses. Kaze Tachinu is to Miyazaki’s career as Ran is to Kurosawa’s- an autumnal, meditative reprise of the director’s major philosophical themes, one that is fluid, bright, and gorgeous.

Would You Prefer a World with Pyramids, or with no Pyramids?

Dear Friend: I recall that, around last winter, you asked what non-Disney films were worth showing to children. Arguably, Studio Ghibli is therefore excluded, on ground of being an acquired subsidiary of Big Mouse. But if you exclude Ghibli and Pixar, I would argue that you are engaging in the worst kind of philistine hipsterism – the exclusion of quality on the prejudice of source. Not watching ‘corporate cinema’ is as ignorant and close minded as dismissing rock and roll as ‘juvenile music’. The work of art is the work of art, and the aesthete should engage the art within the separation from context as well as within the context of the art’s production. If we ration our appreciation only to saintly patrons or to saintly artists, we cheat ourselves into the wastelands of the spirit.

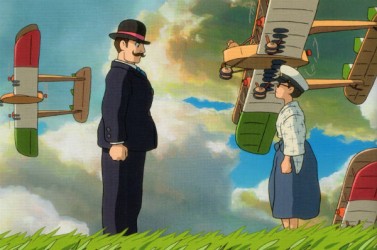

Miyazaki’s film is the biopic of Jiro Horikoshi, one of the lead designers for the Mitsubishi corporation. His most famous airplane design was the A6M “Zero”, the most heavily produced fighter plane used by Japan during WW2.

The A6M Zero was a rapture of engineering, a machine of grace and delicacy. For about a year, the Zero gave the Japanese complete air superiority despite Japan’s shortcomings in metallurgy and engine design. The Zero was all maneuverability and speed without armor; impossible to hit, but shot down with one salvo.

If you’re an aviation enthusiast this film is a must-see. In fact, I’d call it the complete opposite of Planes. Planes made you hate aircraft for merely being the same hackneyed cavalcade of the stereotypes that crass mass culture subjects us to everywhere; Kaze Tachinu shows us how and why generations are entranced by the pursuit of flight. I’d understand if Planes was the inception of your boycott- it made me want to shun all Pixar and Disney films as well. Kaze Tachinu is a medley of fantastic and obscure aircraft- the Junkers G.38, the world’s first flying wing; the Caproni Noviplano, the world’s first attempt at a transatlantic jumbo airliner; the Deperdussin Moncoque, forerunner of modern aviation techniques. Miyzaki’s eye for detail plumbs both the interior and exterior workings of these engineering triumphs. It’s a plane-lover’s dream movie.

The structure of the film roughly follows three acts: two acts tracing the lives of great aviators who paralleled Horikoshi. Count Gianni Caproni and Hugo Junkers, like Horikoshi, were central visionaries of the German and Italian aviation industries, men who had dreams of air-liners that were conscripted instead for the design of war machines. When Jiro dreams of flying as a boy, he communes with Caproni’s dreams. When he begins his career, it is by traveling to Germany to study at the Junkers factory. At last, he becomes ready for his own dreams, and is faced with his own challenge of reconciling ambition, empathy, and obediance.

The question that prefaces this review, as asked by Caproni, is the central theme of the film. How many prototypes must crash into the ground for mankind to fly? How much can these beautiful creations be worth, when measured against the death needed for their creation, and the deaths brought about by their usage?

The Prison of Genius

Ideas, especially good ideas, and more certainly original good ideas, can work a terrible binding on a person. I have known it, as a compulsion to write that affixes me to one spot until the piece is completed. What may be hard for people to understand about pervasive developmental disorder, and if I may, the ‘nerd/engineer’ state of mind is how intellects can become paralyzed by the beauty of ideas. I’ve never seen this condition more beautifully expressed than in this film. Mackerel bones become spines, which becomes the struts of an airframe, which transforms into a sliver plane, flying out of the restaurant and into the blue. Miyazaki animates the process of imagination itself in this film, and the sequences are the summit of animation’s expressive potential.

There is a surplus of films to encourage children to be a princess; or a swash-buckler, an explorer, or some child of inevitable destiny and supernatural potential. There are precious few films that can kindle enthusiasm for learning hard math, calculus, and materials science. Kaze Tachinu is one of the rarest and most precious films because it can speak to the beauty of invention, engineering and design. It’s not a film for every child, and it’s an unusual child that would have the patience to watch this film. But for the quiet child, the introvert, it is a film not to be missed. I am certain that this would have been my favorite childhood film, had it existed then.

War and Peace on the Magic Mountain:

The other major sub-plot of the film is Jiro’s romance with Naoko Satomi, an invented fiction used to give emotional heft to an otherwise aloof intellect. Jiro is first smitten with her during the great Kwanto earthquake of 1923, only to lose her in the ensuing chaos. He only finding her again at his professional nadir, when he takes a vacation after the failure of one of his prototypes. Their romance blossoms in the resort of Karuizawa, in the shadow of Mount Asama. But she is there for her health- she is afflicted with tuberculosis, and she is forbidden to marry Jiro lest he should also become infected.

The key to understanding Kaze Tachinu is to understand that it’s a combination of two major works of German literature: The Magic Mountain, by Thomas Mann, and Mephisto, by Klaus Mann. Jiro Horikoshi is a combination of Hans Castorp, the conflicted ingenue torn between pacifism and national duty, and the character of Hendrik Hoefgen, who pursues his acting career at the expense of becoming a Nazi puppet. These two novels deal with the transition of Weimar Germany into the Third Reich; translated, Miyazaki has made the film about how Showa Japan transitioned into the madness of the Tojo cabinet, and a suicidal war fought against all neighbors.

Like the Szabo’s film classic Mephisto, Kaze Tachinu is a meditation on how the pursuit of aesthetic integrity can be exploited in totalitarianism at the expense of ethics. Jiro attains the construction of his wondrous machine, only to be left to wander in a graveyard of wrecked warplanes. He is not allowed to join his love, who has returned to perish at the mountain sanitorium.

Film critics like J. Hoberman of the The Village Voice think that Miyazaki has softened his pacifism with this latest film, because Jiro apparently doesn’t suffer…enough? The human misery is elided? I disagree, and I’d call this Miyzaki’s subtlest and most powerful anti-war film. At the end of this movie, Jiro is left only with the dreams of the dead- his wife, who he neglected, and the ghosts of all the dead pilots of his creations. His future is only to survive with the memories of all those that have been lost in the fulfillment of his dreams. If you catch that, the film is absolutely emotionally devastating.

Not a Film for the Skylers and Megans of the World:

This is not a movie for the anime enthusiast seeking action sequences. Nor is it a film for those seeking a bedtime story. It’s a slowly building, subtle, winding tale of the travails and sacrifices that are made in the pursuit of genius. But I think this film is a godsend for a rare kind of youth, for those who are contemplative, mathematical, and obsessive.

In the end, my friend, I cannot guarantee that your children will enjoy this film; nor can I guarantee that they will understand this film; but if they are as intelligent as I’ve seen them to be, then Kaze Tachinu will be stimulating to them in a manner unlike any other animated film, and unlike almost any other film made. Tampopo, Amadeus, Pi, and The Black Swan are comparable, but unlike Kaze Tachinu, I wouldn’t recommend any of those others for children.

Persons with a meditative mind will find Kaze Tachinu to be a challenging inquiry into the conflict between morality and aesthetics. It is a singular coda for career of Japan’s greatest animator.