American heroes, past and present, are usually defined by their rugged, can-do spirit; a reluctance to play the champion, sure, but once engaged, feisty, never-say-die creatures of indomitable certainty. These men — always men — may often slink in the shadows waiting to strike, but like Cincinnatus, they are called from a quiet, simple life of tending the fields to serve with distinction, enviable strength, and an unparalleled masculine drive.

Objecting to any exalted status throughout their run up to (and through) the matter at hand, they seek always to remain a humble warrior; a brutal master of fist, foot, firearm, or phallus, if need be, but one never seeking fame and fortune for their own sake. They may get the girl, or stand before roaring crowds, or so vanquish a foe that the world is once again set on its axis of peace, justice, and Christian charity, but offer such a man no more than a firm handshake and a subtle nod. He’ll see that twinkle in your eye, and his muted, soft grin — exasperated and unbearably coy — will be the only evidence you’ll need to know he sees life just as you do. But leave him be; his is a solitary quest, and upon arrival at his destination, he’ll wander off once again, waiting in the wings for that clarion call.

Indiana Jones is just such a man, though rather than farming, he spends his days away from globetrotting in a classroom, enriching young minds in the ways of archaeology. Soft-spoken, clean-shaven, and a vision in mediocre tweed, he is the antithesis of the very spirit he channels while confronting danger in exotic locales. He is the good doctor; a man of chalk, books, lectures, and theories, and despite the expected romance filling the heads of his wide-eyed charges, he insists on dry, relentless fact. Data — what can be proven — is his academic mistress, and he is least tolerant of rumor, superstition, and hocus pocus.

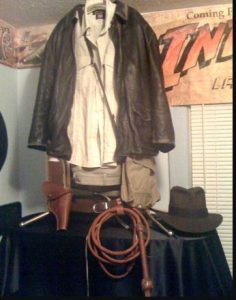

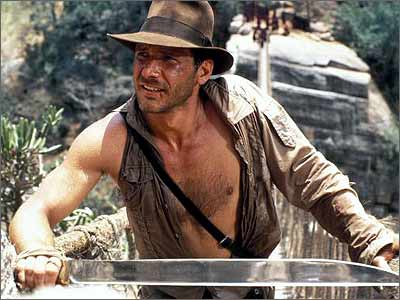

And yet, this is strictly posture; an image of scientific objectivity to uphold, despite the years of contrary experience that all but prove the wild side of spiritualism and fantasy. Dr. Jones is the Clark Kent of the equation; a dull, geeky sort whose eyes pop out in adolescent glee at the mere thought of adding a vital relic to a dusty museum. And yet, he retains his sense of somber duty, and would no more risk his position than traipse through a dig site with reckless abandon. But it’s simply not enough. Dr. Jones could no more invigorate the libido of a lustful strumpet than rouse the average lay about from his slumber with such dreary, doughy intellectualism. He must shed his professorial garb and become the stubble-rich, sweat-drenched Indiana; man of action, man of vigor, and man of flag-waving purity.

If there is a guiding theme to Indiana’s quest for American dominance, it is the fear and suspicion to be cast against the whole of the world found outside our righteous shores. Yes, it is by and large the iron hand of the white male at work, but not at the expense of good sense, for how else to summon archetypal visions of villainy than with our melanin-challenged brethren from Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia? As simplistically reasonable as a united front of white skins would have been for the cause of imperialism, such blatant racial overtones would not have survived the vetting process at the screenplay stage. Stereotypes and insensitivities remain to be sure, and Indiana’s revolution is largely Western in origin, but his whip crack is better thought of as the lash of Americana, rather than a wholesale support of so insidious an ideology as white supremacy.

It’s fair to wonder if Spielberg had not been aboard whether or not the enemy of the original trilogy’s bookends would have had the darker hue of the second, more obnoxiously insensitive installment, but it’s impossible to know for certain. After all, the entire idea of the series is so in line with Spielberg’s vision of a dichotomous universe (saints and sinners) that it took his stature to get it off the ground in the first place.

And let’s remember that above and beyond the fever-pitched defense of, in turn, Biblical relics, enslaved little brown ones, and again, Biblical relics, there is the oft-repeated Spielbergian credo of masculine virtue. Again, and again making up for an absent father, little Steven pines for the lost comfort of a bedtime story of mid-afternoon hair tousle by having his adventurers drive into the heart of danger, as if always chasing parental approval. Not so bad in itself, of course, unless one fancies more than the archaic reinforcement of gender roles last seen in turn of the century melodrama. Men get scarred, scratched, beaten, and, yes, smacked repeatedly until that dab of blood appears in the corner of the mouth. In contrast, women are dames, babes, or chicks; reduced in turn to their parts, though conveniently nothing northward of the heaving bosom.

Even the more jocular of the bunch, Miss Marion Ravenwood from Raiders of the Lost Ark, is not beyond a drinking contest with hardened Nepalese mountain men, but the swagger and hint of chest hair beneath the feminine attire quickly yield to helpless yelps and groan-worthy sarcasm, in women always the first refuge of the scoundrel. Indy clearly left this broad in a lurch, and within a few moments, our sympathies are decidedly with the only penis left standing. Even her so-called bravery is accidental, and though using a closed-fist to strike her former (and future) lover, she’s all petticoat when nature calls. Aiding no one, she seeks said aid at every opportunity.

The fairer sex continues its slide once The Temple of Doom swings around, and it’s telling that the set of gams in question belong to the main squeeze of the mighty director himself, one Kate Capshaw. It’s not simply that she’s a two-fisted argument against all forms of nepotism, or that her performance is more akin to a cocktail waitress finally getting that big break in her community theaters’ production of Our Town, but rather it’s the sheer passivity of the role that grates right down to the marrow. While Indiana dashes, dives, and wipes his brow, Capshaws’ Willie Scott (masculine in name only, I’m afraid) snorts, wheezes, and whines like the girl who gets popped by the second act for the simple crime of annoying the heavy. At one point, and on several occasions thereafter, Willie cries, “I cracked a nail!” as if for all time suggesting the only manner by which to judge the whole of the female race.

Further, her “I hate being outside!” declaration makes her a creature of indoor living; soft, simple, and sexy, but not at all akin to being taken seriously. As such, she’s the embodiment of Indy’s worldview, one that asks one-half of humanity to ride along in the sidecar, so long as they don’t get in the way. But get in the way they do — repeatedly, in fact — making the job of saving humanity that much more difficult. It’s likely that Spielberg thought he was doing his wife a favor by casting her in the Dizzy dame role, perhaps making her a Rosalind Russell for a new generation unfamiliar with the type. Russell cracked nuts between her knees and had the likes of Cary Grant stammering for breath; Capshaw’s ill-equipped to so much as send her male companions into a fit of eye-rolling pity.

The dames fare no better as the series wears on, becoming Nazis in disguise or recycled flames from screenplays past, but at least they can be dismissed with a chuckle or slight shove. Those not blessed with voices clear and strong and accented firmly on the North American continent are not only questionably human, but most certainly uninterested in girls at all. Indiana’s lust for the ladies is established early, often, and ad nauseum, not because he slips into assorted sheets on his travels, but rather because he is not what he opposes. In sum, he recoils at the swastika.

He is a study in contrast; not a coward, not a bully, and not a limp-wrested, mincing queer in jackboots. The homoerotic underpinnings of National Socialism have been written about at great length, but never before have such theories been grabbed by the lapels and ushered before a cinematic audience with such conviction. Nazi Germany failed to rule the planet not because British, American, and Soviet forces drove the desperate armies to the brink; instead, lisping queens with propensities for spontaneous giggling brought down the empire by not fighting for family. Sado-masochistic, fetishistic, welts-across-the-back obsession, perhaps, but not the need to have a man and a woman firmly in their place. The only female Nazi worth a damn humorlessly uses her wiles to seduce, then, feeling unclean, quickly re-appropriates the accoutrements of a self-loathing man.

And let it be said: Indy’s sneer in the face of Hitlers’ hordes has little to do with their policy of incinerating European Jewry, or invading sovereign nations by the Panzerful. During The Last Crusade, a full year before Poland gave up the ghost after struggling mightily over a brave weekend, Indiana states, “Nazis!. I hate these guys. Even Indy’s father (played for no apparent reason by Sean Connery), calls them the “shame of humanity.” Really? Before the liberation of the camps? Few overtly romanticized the Nazi menace throughout the 1930’s, but a hands-off isolationism was much more likely than a bold stance against a nation that put on one hell of an Olympics. What are the odds that the two Jones men, bickering with each other, yet united in loathing histories most appalling boogey men, would see into a nation’s intentions where the world entire saw only reasonable annexation?

Perhaps Indy found a crystal ball in his assorted travels, but it’s more likely that he is merely expressing the character’s inherent wisdom as an American hero. Would that shallow politicians and yellow-bellied bureaucrats have heeded the advice of the Father and the Son. And when our man of the hour meets the vile Hitler face to face? No Joe Kennedy handshake for this guy, no sir. Instead, a stare of piercing disgust; and a stand-in for all of us who woulda, shoulda, coulda had he not been surrounded by vicious, leather-clad Gestapo goons.

Okay, so Indiana’s white skin wasn’t exactly the unifying element it could have been, but surely we can agree that his perspective on Asia wouldn’t pass muster in the history department down the hall. For Temple of Doom alone, the crimes of Nanking fear a finisher from several furlongs back, and Indy as hero can at last cast his lot with the overtly bigoted. It’s curious that alone among the four films, this one avoids totalitarianism with almost gleeful vigor, as if, finally unhinged from obligatory symbols of evil, the series could place the Third World in the proper perspective. The sequel to the immensely popular (and still fan favorite) Raiders, it couldn’t possibly measure up, but who knew that Stevie baby would check his sensitivity at the door and go completely unhinged. It’s as if, drunk with power, Oscar nominations, and the rationalization that eventually, he’d make his career-capping apologia in the form of Schindler’s List, Spielberg bared his teeth, flashed a bit of all-American arrogance, and served the whole of the Asian madhouse on a steaming hot platter of hatred.

Shanghai hits first and most appallingly, coming off as little more than a den of iniquity unparalleled even in a decade that witnessed mass slaughter on an unimaginable scale. It is peopled by whores, thieves, scumbags, and diseased gangsters, even though George Lucas tried to remove a bit of the sting by naming the place the “Club Obi Wan.” Not funny then, nor these decades later, and not even enough to make us believe they had their tongues firmly in bearded cheek.

The breathless pace continues almost unabated, pausing only to give us the sort of airplane that, having run out of fuel, crashes and explodes as if loaded to bear for a global journey, as well as a curtain-raising on one of Steven’s most shameful hours: the lonely figure of Short Round. Shorty, if you will. Making Mickey Rooney’s buck-toothed landlord from Breakfast at Tiffany’s seem like a cautious, politically-correct study in restraint, Jonathan Ke Quan’s minstrel show is just about the only thing that can challenge Capshaw’s crowning achievement in embarrassment, but it succeeds so wildly as to nearly mute the cawing vagina with a single stroke.

From his broken Engrish to his wide-eyed look of astonishment at everything save nuance, Shorty is the sidekick no film dared approach since the dawn of the civil rights movement. Comic relief can rescue a film to be sure, and often provide the necessary contrast to an ever-serious leading man, but has central casting ever sent out one of their indentured servants on so hopeless a cause as this? Are we not supposed to laugh as we grip our seat with anxiety, not pray to holy Vishnu that the youngest member of the cast is separated from his entrails and paraded in maximum writhing before roaring crowds? Should we count the seconds until the ultimate weapon — removing a heart from a vanquished enemy’s chest — is performed on the one cretin shoehorned into the screenplay to elicit gurgles of joy from the mom set?

Hate rears its head among the faceless as well, with teeming Indian masses reduced to primal wails and exotic tongue-spinning. Nazis might appear to have little on their minds but sending their hardened troops into subdued anal passageways, but at least they stand out as individuals from time to time. They are granted a bit of agency. Not so for our Hindu brothers. Reduced to sitar music, bizarre rituals, and an economic structure based on cruelty and child labor (okay, so maybe that’s not entirely unfair), the East, at least in Indy’s world, is among the nastiest ever put on film. And did I mention that their child king is a little light in the loafers? Then, as if we didn’t get the message, the film features a much-discussed centerpiece where our innocent, steak-and-potatoes eating Americans are made to endure the dining habits of the savage: snakes, bugs, eyeball soup, and for dessert, monkey brains, served in the still smirking heads of the deceased.

Indy may feign objective interest while clutching his dusty tomes within the safety of his academic tomb, but deep down, he knows damn well that he’s risking life and limb every time he leaves his glorious homeland. After all, only there, with the Other, does he encounter the sick, the depraved, and the truly apocalyptic. As a worldview, it’s akin to assigning America to the angels, and the rest of humanity to the stench and grind of the sty. Sure, Our Man Jones deserved our eternal gratitude for snatching shiny objects from the clutches of beasts, but we’re also tempted to pull him back from additional risk. Must our saviors, the enforcers of our very way of life, insist on getting dirty? Or are their sacrifices the only way to shield us from sin?

At last, and for all time, Indiana Jones shoves his mighty oak of an arm, browned by the sun, cut and clipped by wars and rumors of wars, into the orifice of unbelief to rescue the very word of the Almighty. Jones is no missionary, and he’s unlikely to say grace before dinner, but he’s a warrior for God nonetheless — Spielberg’s son seeking the father who didn’t have time to throw the pigskin after the table’s been cleared. He’s the only one who can travel the globe and show the heathens the absolute power of the Holy Spirit, vengeful as it might be when disturbed from its slumber of not saving children and Jews his own damn self.

It’s a curious deity to be sure, one not meant for church, or Bible camp, or holy-rolling, but rather sheer, unvarnished reverence; taking ancient texts and truisms so seriously that stealing them away from their final resting places is enough to crack the universe in half. Indy, then, is at best a restorer, a simple soul who senses a spiritual disruption and, pausing only to run roughshod over brown brutes who dare traffic in soulless desecration, re-orders the universe as God (and the hundreds of little elves who helped construct elaborate puzzles and riddles to give explorers a chance, after all) whispers to the wind that after an eternity of work, he just wants to be left the hell alone. My Ark, my cup, my token of amusement. So, what if I left a few loopholes for the curious and the clever; I’ll strike thee down if you get close enough to the real mystery at hand.

So, Indiana worships an Old Testament Yahweh; you expected Spielberg to erect crosses along the way? But Indy’s protection of God’s toy chest is down the line an American proposition. For all our talk of love and justice, we still like a good knife fight, and the bigger the erection sported by our divine redeemer, the more soundly we’ll sleep in our suburban cocoons. Those melting faces stand for all time not as the best possible effects from the era, but rather as a warning to all who dare spit in the eye of Lady Liberty. God is on our side, and we know better than to dig up what he buried so long ago.

All at once and with great force, the films suggest that we need the big guy in our huddle, but we’d rather not know the answers to the really big questions. We need the unknowable, after all, lest we look too closely and see how indistinguishable from an especially bad comic book the whole damn thing really is. With Indy to save these physical manifestations of religion’s pull from those who would dust them off and strip away all allure, Americans can remain cloaked by a sky that still harbors a God of awesome power and unpredictability. We can never know the ways of the Lord, we humbly attest, and in the end, we want it that way, or else. For if we’re allowed to peek inside that box, absent flame and shockwave, we might indeed wonder why in the hell God didn’t take the whole week off. More ominously, we just may see him as a reflection of our worst instincts, rather than an object of worship.

By the time we reach the final installment, Spielberg’s worldly obsessions have become truly universal, and actual aliens add to the mystical soup, albeit with the same dire warning. Knowledge is perilous, and we must enlist the aid of the ruggedly handsome to ensure that answers never outpace the questions. The questions themselves are a pesky irritant, but inevitable as they are, ignoring them does little to keep the house in order. Indiana Jones, by day a boyish academic harmlessly lording over the classroom, is by night a fierce defender of the realm, where competing interests threaten to blow the whole damn thing apart.

Foolish idealists in schoolyards can spin their pencil under the pretense of solving the world’s great problems, but outside those doors, windows, and ivy-covered walls, lies a man’s paradise; where all is made safe for the privileged and the protected. Pasty Americans may not have invented the very issues and ideas discussed herein, but they’d like to believe they’ve crystallized them to their best, most lasting purpose. Man in his place, woman in hers, the barbarians ever after outside the gates, and the brain never so taxed that it can’t defer to the muscle and the machine. Around and around and back to the essential truth of our time: for all of our talk of individualism, decentralization, and flag-fisted freedom, it is the authoritarian heart that beats in our collective chest, and whether by tools of race, gender, nationality, or sexuality, we’ll see the battle through. Until the home fires burn once again. And Indiana Jones tips his cap, throws us a sly grin, and takes leave for yet another adventure.

Leave a Reply