The Hospital (1971) If there is one thing that separates the classic films of the 1970s from today’s offerings (outside of mere competence), it is great dialogue. Words that snap, sizzle, and exist far beyond the need to push the story forward. More than that, I am speaking of the sort of dialogue that challenges, pushes, and exposes, rather than obsessing over pop culture and pseudo-cleverness in the manner of Tarantino and his bastard children.

The Hospital, Paddy Chayefsky’s brilliant, powerful indictment of American life – under the guise of a hospital expose – is just the sort of film I live for because it believes that the words of cinema are sacred and deserve (demand) to be listened to in the same manner as a theatrical drama.

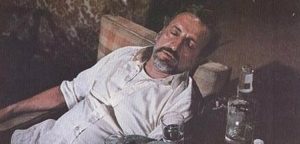

I have seen The Hospital at least a dozen times, and I will see it a dozen more, and yet the familiarity breeds only a stronger, deeper appreciation of the language and performances. At the center of it all, however, is George C. Scott. Perhaps he has never topped the mad brilliance of Patton (find me an actor, dead or alive, who has), but I would rank his world-weary doctor as one of his – and cinema’s – finest hours.

Over the course of nearly two hours, Scott spits, rages, roars, bellows, and towers over his co-stars with a magnetism and power that is nearly unmatched in the annals of Hollywood. There is never a time of day I could not watch, or even just listen to this film, and I credit Scott for making it one of the finest cinematic experiences I have ever had in front of a television screen. The announcement of the film’s long-awaited release on DVD is an event of such magnitude that it cannot be described to the uninitiated. If you’ve seen The Hospital, you’ll understand.

Some have called Chayefsky’s screenplays “talky” and not really screenplays at all, but rather a series of theatrical monologues with no real drama. Fuck ’em. Any human being who can write dialogue of such savage power deserves to be put on a high pedestal and never criticized again. That such a script won an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay is an absolute miracle, given that this film is as vicious and uncompromising as any ever penned.

And usually, Hollywood is reluctant to endorse any film that avoids – even mocks – the idea of redemption. Instead of coming to his senses and vowing to change his life, Dr. Herbert Bock (Scott) shuffles back into the cyclone of a hospital as his friend shrugs, “It’s like pissing in the wind.” One can imagine that Bock will attempt suicide once again, as he did during the film. His “redemption” is temporary, and his passion for life will last only as long as the walk back to the center of the storm.

The film wanders from room to room in a big city hospital, demonstrating the bureaucracy, incompetence, and greed that dominates American health care (as with Network, Chayefsky was prescient beyond belief). There is a “murder mystery” of sorts, whereby several doctors are found dead without explanation. When the murders are solved, it is not as we would have expected, but only adds to the insanity of our culture. There is also a “romance,” although it would be better to describe it as Bock does of his failed marriage: “Clearly sadomasochistic dependency.”

The woman, Barbara Drummond (Diana Rigg), is a loony flower child who falls instantly in love with Bock after interrupting his suicide attempt. Being a Chayefsky screenplay rather than typical Hollywood junk, the relationship proceeds cynically as Bock rapes Barbara in “a suicidal rage,” as he describes it. After the rape, she declares her love. She asks him to leave the hospital and run away with her to an Indian reservation where he can “matter again.” It’s a romantic idea, and he seems to want to follow through, but he is enslaved to the shattered remnants of his life.

“Somebody’s got to be responsible,” he states firmly, although we know he doesn’t really believe it. But then again, he might. Chayefsky, despite being a potent social critic, had deep reservations about the younger generation of his time and saw them as deluded, idealistic fools.

Bock may be on the brink of madness, suicidal, and hopeless in both work and marriage, but at least he lives in and understands the real world. While his kids are dropping acid and building bombs, he is doing the grunt work that allows these spoiled snots the comfort and prosperity to live as “rebels.” For Chayefsky (through Dr. Bock), the young are silly, self-serving, opportunistic, and utterly phony. Given the trust-fund radicals I currently see and believe to have composed a large segment of the hippie set, I can’t say he’s wrong. Chayefsky knows – as I believe now – that the campuses of the 1960s didn’t start erupting until student deferments no longer protected the privileged from the draft.

Chayefsky states similar messages in Network — black power movements are profiteering sellouts, America is awash in loveless sex and shallow relationships, and religious fundamentalism is as natural to our culture as murderous violence. When Bock snaps, “Everybody lives with lies,” he is not only refuting his son’s idiotic self-righteousness, he is belittling our continued belief that we are a truth-seeking populace. Even the grand hospitals, testaments to our richness and technological might, are illusions as we, in his words once again, “cure nothing and heal nothing.” Think of this rant:

“We can practically clone people like carrots, and half the kids in this ghetto haven’t even been inoculated for polio. We have established the most enormous medical entity ever conceived, and people are sicker than ever. We cure nothing! We heal nothing! The whole goddamned wretched world, strangulating in front of our eyes.”

Of course, it’s that much better with George C. Scott spewing forth, but the words are so bitter and so pessimistic that any Hollywood producer today would demand a rewrite. What we have the AMA and insurance companies to consider! Okay, I’m rambling, glowing perhaps, in my memories of this film. I love every word, every frame, and every performance with an intensity I usually reserve for hating religious conservatives. But yes, I too can feel joy. To quote another Scott creation, “I do love it so.”

Leave a Reply