The Exorcist III (1990)

The Exorcist was a profanity-soaked horror milestone. Its follow-up was smeared in locust shit and as amusingly bonkers as they come. However, Linda Blair wasn’t required for the second sequel, enabling its producers to try a new approach. Exorcist III is not a reboot (like the deliriously kooky Halloween III) but it does manage to chuck out half the bathwater and the baby’s head. Its chief connection with the first two entries is that our two main characters knew Regan’s doomed savior, Father Damien Karras (Jason Miller). Otherwise, this dose of satanic evil takes the form of a long dead serial killer apparently still at work.

Lieutenant Kinderman (George C. Scott) is a world-weary cop while his mate Father Dyer (Ed Flanders) is a good-natured priest. They like to go to the cinema together and afterwards gently butt heads over the world’s ever-present scourge of wickedness.

“We have cancer and mongoloid babies and monsters prowling the planet, even prowling this neighborhood,” Kinderman says, “while our children suffer and our loved ones die and your God goes waltzing blithely through the universe like some kind of cosmic Billy Burke.”

The Catholic response? “It all works out right. At the end of time. We’re gonna be there. We’re gonna live forever. We’re spirits.”

Excuse me while I groan. One point of view offers hard truths; the other the most hopeful fantasy. Nevertheless, it’s clear there’s a deep respect and camaraderie between these two men and perhaps even love.

Kinderman has got so jaded and cynical because he constantly has to clean up the worst results of human behavior. In the latest example, a twelve-year-old black boy he vaguely knew has been killed. Actually, ‘killed’ is a bit of an understatement. The kid was first injected with a paralyzing agent that kept him fully conscious throughout. Then he was crucified and an ingot driven into each eye. Next his head was cut off and replaced with one from a statue of Christ.

Pretty horrible, eh?

Except we’re not finished. Christ’s face was changed to blackface, complete with minstrel-like, painted white eyes and mouth.

Fair play, you have to applaud such prolonged, unabashed sadism, especially as the perpetrator then has the nous to turn his meticulous handiwork into a fantastically insulting joke. No wonder Jeffrey Dahmer was reportedly a fan of Exorcist III.

It’s moments like these that help us grasp this flick’s dark potential, especially as the good scenes keep coming. Watch how a doomed priest in a confession box grows perturbed by the voice of a little old lady alongside as she starts off sounding like a pedantic pain in the arse before admitting to seventeen murders, the first being a waitress in a nearby park. “I cut her throat and watched her bleed. She bled a great deal. It’s a problem I’m working on, Father. All this bleeding…”

Written and directed by the key man William Peter Blatty, Exorcist III is based on his 1983 novel, Legion (a work I need to read). Ultimately, it becomes a frustrating watch in that his film was hacked apart by the studio in a bid to make it more mainstream, partly by insisting the word exorcist appeared in the title. That’s the reason for those clunky, obviously inserted scenes with a white-haired priest and the unnecessary exorcism finale. This is a terrible shame because before the fifty-minute mark Exorcist III is on course to become a classic.

However, even in it mutilated form it gets a lot right by dragging in a Carrie-like emphasis on blood, near-constant religious imagery, some terrifying-looking stainless steel autopsy tools, John Donne’s most famous poem, the camera prowling the wet, night-time streets, senile geriatrics, black comedy, frequently pithy dialogue, those scary long flight of stone steps that Karras took his tumble down in 1973, a handful of superb scenes set in a psych ward, and the killer having a sick, mocking sense of humor and fondness for showmanship that, on my more deluded days, I like to think he stole from me.

Damn the studio and its hack job. We can only pray that a director’s cut will one day emerge.

Then I might start believing life is wonderful(l).

The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Here in Oz, there are a couple of national parks in the Top End. I’ve visited both. One’s called Kakadu (where Crocodile Dundee was partly filmed) and the other’s Litchfield. The world heritage-listed Kakadu is the size of my home country, Wales, and a goddamned wonderland teeming with tropical wildlife. On my travels, however, I’ve bumped into folk hailing the much less famous Litchfield as superior. I suspect they think that by going against the consensus they’re trying to present themselves as interesting, knowledgeable and discerning individuals.

Contrarians I call them on my more generous days. Yawn-inducing dicks on others.

It’s the same with 1986’s Manhunter and its very loose continuation, Lambs. Some people insist the former is better. They think Brian Cox’s understated performance as the cannibalistic serial killer is the more memorable.

For fuck’s sake, you gotta be kidding.

The box-office flop Manhunter is not bad at all, but Lambs is an indelible piece of pop culture anchored by Anthony Hopkins’ mesmerizing turn. The one’s fava beans and a nice Chianti, the other’s fish and chips with Coke.

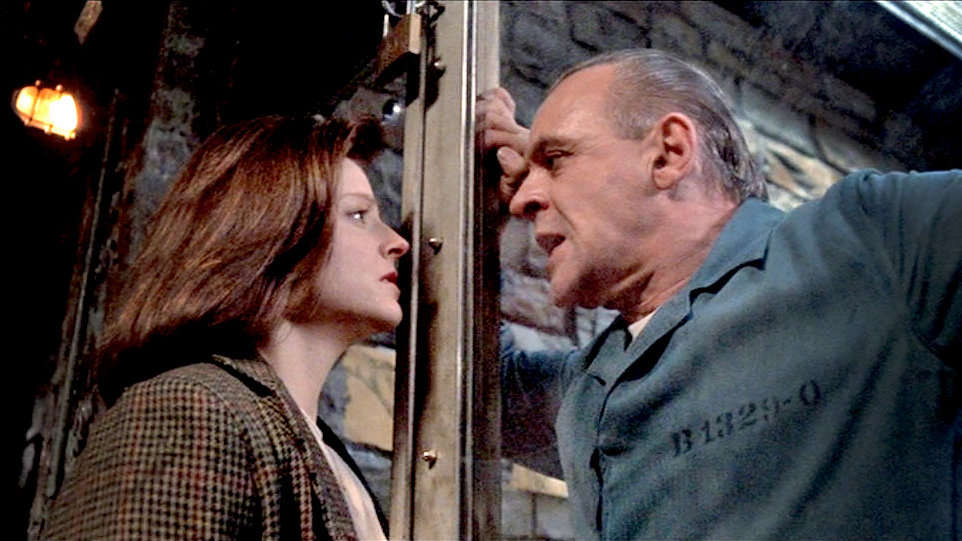

Lambs kicks into unsettling life when we accompany the ambitious FBI rookie Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) into the lions’ den at a hospital for the criminally insane. It has to be said that you don’t expect a line like “I can smell your cunt” in a major Hollywood production. Still, it’s a fitting bon mot for this human zoo, a place where the deranged, highly dangerous inmates are in various states of distress and undress.

Except Hannibal Lecter, of course.

His glass-fronted cage at the end of the row immediately gives off a different vibe. For a start it’s better lit and more orderly. Even the brickwork appears cleaner, less dank. Then there’s the man himself standing to attention with his slicked back hair and penetrating gaze. Within a couple of minutes, we learn he’s intelligent, softly spoken, polite, playful, super-observant and uncannily perceptive. This is a cat-like, borderline supernatural presence whose eerie stillness doesn’t match the horrific violence we know he’s capable of, violence that can erupt in the blink of a jaundiced eye. What’s also noticeable is how comfortable this guy is in his skin. He might be an absolute fucking freak who dines on torn-out tongues and tales of childhood trauma, but he doesn’t do flustered. Even more oddly (and despite his radically reduced circumstances), he appears in charge.

Starling, however, is having a far tougher time in her cheap shoes, an uncomfortable journey that doesn’t get any easier after fleeing the madhouse for some much-needed fresh air. For she has to make her way in a world of men. Macho cops tower over her, obviously thinking such a Silly Girly has no place among them. Others hit on her instead of doing their jobs (“Don’t you feel eyes moving over your body, Clarice?”) One even tries to kill her. Even a good guy like her boss Crawford (the gaunt Scott Glenn) occasionally treats her differently because of her gender.

In a way, this is good. It forces Starling to develop resourcefulness, courage and a steely inner core. Yes, she’s sensitive, self-conscious, vulnerable and occasionally sporting a face spattered by a sex offender’s hurled cum, but that doesn’t stop her backing down from the bunch of condescending, sexist and plain dangerous male fucks all around. Not once does she morph into a gung-ho ass-kicker, though. This, ladies and gentlemen, is how to do a Strong Female Role.

Lambs remains a tasty adult treat, its dark psychological power never less than compelling. Sure, every aspect of Lecter’s daring escape (from the moment he apparently wills a pen into his hand to paramedics being unable to work out a patient is wearing a false face) is ridiculous, but Lambs‘ surfeit of brownie points elsewhere ensures we never tut-tut too much. Indeed, you know a movie has succeeded when our charming, newly liberated madman jokes he’s about to ‘have a friend for dinner’ and we smirk along with him.

I wonder if he’ll visit Litchfield on his travels.

What Becomes of the Broken Hearted? (1999)

OK, time to check in on our favorite volcanic Kiwi nutter, Jake the Muss (Temuera Morrison). When we left him at the end of Once Were Warriors he was outside a pub ranting at his fleeing wife with the veins bulging on his forehead after having beaten the shit out of a former mate. In other words, trying to deal with a few anger management issues.

As Broken Hearted opens, not a lot’s changed. He remains brawny and shaven-headed but at least he’s not busting heads, instead happily partaking in a pub sing-along. Then his fatal flaw … machismo… kicks in and he’s giving a couple of dudes that awesome, paint-peeling stare. “All they’re doing is looking at us,” a mate tells him. “You’re too old for that shit.”

Nah, he isn’t.

Jake strides over and leaves them in a bloody heap before returning to his table to carry on singing, as if having done nothing more noteworthy than taking a leak. Leopard can’t change its spots and all that.

And yet Broken Hearted concentrates on Jake’s attempt to shake off his lifelong affliction. Not that he’s too successful to begin with. After all, getting wankered, hurling disobedient women around a room, and publicly breaking jaws is his specialty. He’s a crude, unenlightened motherfucker. Women are the ‘curse’ of his life and he’s forever looking to blame others for his awful mistakes. Eventually he’s barred from his favorite boozer and is forced to try a new one. He gets into a fight straightaway, causing the rest of the pub-goers to back off, as if a virulent disease has entered the premises.

Bit by bit Jake gets more and more isolated, forcing him to confront a new emotion: loneliness. This pushes him into seeking out his ex-wife Beth (a barely used Rena Owen) to hesitantly try to explain his nature. “I never used to think about it before,” he says. “I just thought it was normal. You know, when I was growing up, that’s all I saw. The old man hitting the old lady. Uncles hitting aunties. They hit us. Sometimes everyone was hitting everyone.”

Morrison’s performance, in which anger and confusion drip off his burly frame, is almost as eye-catching as the first time. He’s a stunted human being, all right, with an acute inferiority complex that he tries to drown in alcohol. Nevertheless, he isn’t beyond hope, although he’s never gonna win any father of the year awards.

Ultimately, however, Broken Hearted delivers a confused message about violence. It’s a messy, half-decent continuation that delves into the misogynistic, self-defeating world of Maori gang culture.

T2 Trainspotting (2017)

Like Psycho II and The Color of Money, T2 took more than twenty years to arrive.

It deserves mention as it’s hard to think of a flick so in awe of its predecessor. Indeed, it spends an overlong two hours cowering in that seminal classic’s shadow, offering frequent flashbacks, reminders, re-enactments and acknowledgments. It’s almost paralyzed with fear at doing anything that might veer away from the original’s blueprint, leaving T2 choking on nostalgia.

It’s overwhelming problem is the ‘tourist in his own youth’ Renton (Ewan McGregor). In the first movie he was a hedonistic, unapologetically amoral parasite. Now he’s a married accountant who goes jogging. Are we really s’posed to root for this depressed, conscience-stricken, self-pitying sell-out? His worst moment arrives when he dredges up and modernizes his epic choose life monologue. As he takes an awkward swipe at iPhones and Facebook, the flick grinds to a self-conscious halt.

Elsewhere, Spud is dabbling in boxing and trying to commit suicide, Begbie has grown grey and predictable, Sick Boy is blackmailing a deputy headmaster, and a redundant new character by the name of Veronica briefly goes topless.

Then there are the contrivances, such as Begbie escaping from clink at the same time Renton returns to his old stomping ground. Other episodes are plain forced, like a sing-along in a Protestant club and Kelly Macdonald popping up as a smartly dressed lawyer. The soundtrack is mostly inferior and vaguely annoying. There’s still some energy in the direction but the freeze frames, snippets of animation, visual tricks and other flights of fancy feel run of the mill.

T2 is passable, but it’s the celluloid equivalent of looking at a fax of the Mona Lisa. Spending time with an impotent Begbie proves about as enticing as the prospect of watching Jake the Muss help little old ladies across the road. Maybe I’m being too harsh, but I can’t help suspecting a staggeringly brilliant flick like Trainspotting is a dynamic one-off that should be left well alone. In that forerunner Sick Boy outlines his philosophy about vitality, especially when it comes to artistic output. “At one time,” he tells Renton, “You’ve got it, and then you lose it, and it’s gone forever.”

Prophetic words when it comes to T2 and the vast majority of sequels.