Grovel Before God, You Maggots!

In the beginning back in 1988 a six-foot-four deity who shunned goofing around arrived in moviedom. It wasn’t long before he began to generate wall to wall adoration by being outstanding at whatever job he did, never showing fear despite the ever-present threat of death, and snapping the limbs of any bunch of displeasing bozos that littered his way. This was no mealy-mouthed Jesus, spouting that contemptible turn the other cheek, blessed are the meek shit. Oh, no.

For this was Steven Seagal, a thirty-six-year-old colossus with a holy philosophy that we shall call… aikido. In our Lord’s nuanced debut, Above the Law, one unenlightened foe dismisses this wondrously fresh way of life as ‘chop suey crap’ not long before a disgruntled bar owner (while surveying the wreckage of his establishment) tells the cops: “He was doing outer space kind of stuff, putting my customers in orbit.”

Ah, well, scumbags and the excoriating purity of aikido never mix well. That’s why in Mr. Seagal’s universe cynics get punched in the balls, an abusive pimp is flung around the street by his tie, a fleeing drug dealer is kicked through a fence, a rampaging Mafioso is halted by a brain-piercing corkscrew, and the spine of a dreadlocked crime lord ends up dislocated over a knee. Just as Luke Skywalker’s power to overcome evil was built on the Force, Mr. Seagal’s immense wisdom, deep love of humanity and furious physicality are intricately connected to his mastery of this lethal martial art.

His fighting style is different to those wussy wannabes Norris and Van Damme in that he waits for opponents to attack and then uses their blundering momentum against them. Its joyful expression includes forearm throat smashes, wrist locks, and lots of bone breaking. Plus, Mr. Seagal will always stand up for the little guy, especially if this gives him the chance to demonstrate his moral superiority by inflicting the same public humiliation a bully has just doled out.

To underline his untouchable level of toughness, Mr. Seagal prefers to fight unarmed, never caring if a challenger is wielding a machete, baseball bat, machinegun, or nuclear-tipped Tomahawk. Sure, he’ll improvise and pick up whatever’s handy, such as a coil of rope or a pool cue, but usually he lets his menacing mitts do the talking. For example, in Hard to Kill he’s confronted by four armed robbers in a corner store. He disables three with the minimum of fuss before contemptuously dropping to his knees to deal with the last knife-brandishing thug. “Come and get some,” our shortened hero taunts the skuzzy crim before flipping him over and wrenching a leg until it pops at the knee. Yes, such adversaries do have a tendency to panic, bellow and charge, but I bet you’d behave similarly in such a bowel-loosening situation. Talk about trying to bat aside a hurricane with a tennis racquet. And yes, the ease with which Mr. Seagal relieves wrongdoers of their weapons does border on magic, but let us not forget: God is a supernatural being, a miracle worker par excellence.

In short, bullets won’t stop him. Neither will a craftily placed bomb, an excavator’s serrated jaws or even a seven-year long coma.

No wonder this action idol hit the ground running, scoring five consecutive hits between 1988 and 1992, four of which debuted at the top of the US box office. His biggest success, Under Siege, racked up more than one hundred and fifty mil and even garnished two Oscar nods. Mr. Seagal’s uplifting message was out and the newly converted believers were flocking to his ministry. Nothing could slow such a cinematic demigod until he chose to clamber onto an environmental soapbox during the torturous finale of 1994’s On Deadly Ground to finger wag we dumb schmucks about raping Mother Earth. Now I’m sure you’ll agree blowing a baddie’s lower leg off with a shotgun or pinning a gangster’s hand to a wall with a meat cleaver are things we can all readily get behind, but being lectured?

For three and a half minutes straight?

Things were never the same for ‘Officer Big Shot’. A mere two years later a supporting role awaited in Executive Decision in which, heaven forbid, he died.

God, it appears, was not only fallible but mortal as well.

Still, we shall always have fond memories of his first five flicks, the key ingredients of which made his bouts of ultraviolence such a mindlessly entertaining watch.

Hairdo: Seagal’s hairdo is fitting in his patchy, mullet-infested debut, Above the Law, in that it’s not quite right. It’s a little unformed, although you can see it’s trying to coalesce into something. But what? Those straggly follicles budding on his nape are as indistinct as an eleven-year-old girl’s ghostly chest bumps. However, it’s the sight of his receding hairline that makes me suspect, no, realize, there’s something wrong with the film stock. Or maybe an internet japester digitally altered it. Whatever the case, it’s an affront seeing a balding Seagal with wishy-washy, collar-length hair. Just picture a roaring lion with mange and you get the idea. No doubt if I took the trouble to download a different copy, he’d be restored to magnificence.

By 1990’s Hard to Kill such hirsute glitches have vanished. Seagal’s no longer thinning on top and that unkempt nub of neck hair has bloomed into a beautiful ponytail that his devoted wife loves to fondle. Ladies and gentlemen, we have liftoff. You thought God had a flowing white beard but in fact he’s the proud possessor of a sleek, five-inch ponytail. It’s fair to say it’s vastly superior to the oily, semi-permed, mullety monstrosity that the pretender Van Damme later sports in Hard Target.

In Seagal’s third outing, Marked for Death, we get Peak Ponytail. It’s now the best part of a foot long and a thing of extraordinary beauty, gaily bouncing and swishing around as he runs after men in need of chastisement. One year later in Out for Justice, the ponytail remains a crowning jewel. At times it appears sentient, even threatening to out-act its host. Unbelievably, we get a sneering comment from one bigmouth gangster who tells Seagal: “I see you still comb your hair like a girl.” Lordy, you’d have to revisit The Exorcist to find such appalling blasphemy. At least the aforementioned hoodlum ends up flat on his back with a broken nose.

Religion: In Seagal’s first three flicks we see a christening, a sermon, prayers said with his children, and a respectful tone in general toward Catholicism. This is a bit of a surprise as I expected Seagal to worship himself. What on Earth does he need such baloney as Catholicism for? But after shooting dead a topless hooker in Marked, he goes to confession to reveal he’s not quite as morally upright as we all thought. “I’ve lied,” he tells the priest. “I’ve slept with informants, I’ve taken drugs, I’ve falsified evidence. I did whatever I had to do to get the bad guys.”

Now I know Romanism should never be taken seriously, given that it’s done nothing but plunder, oppress, abuse and hold back genuine knowledge for two millennia, but the priest who listens to Seagal’s litany of woe arguably offers the most stupid bit of advice in its long, unfortunate history. “Try to find a gentle self inside you,” he says. “Allow this person to come back.” Good grief, doesn’t he know Seagal is pure Old Testament? Unsurprisingly, such daft religious counsel is ignored and an avalanche of slaughter is instead unleashed on the streets of Chicago.

Is he hero-worshipped? Do other men want to bum him? At the start of the explosion-heavy Deadly Ground expert fire-fighter Seagal steps from a helicopter to tackle an out of control oil rig blaze that’s already killed three men. The sight of his arrival prompts the mightily relieved foreman to exclaim: “Thank God!”

No, mate, thank Seagal.

It’s not universal acclaim, though. Gangsters, bullies and terrorists hate him (even if they tend to respect his counterattacking capabilities). Just listen to bad boy Gary Busey in Siege after Seagal has punched him: “Now I know why you’re a cook. You hit like a faggot.” Environmental rapist Michael Caine goes further in Deadly Ground by telling a henchman: “Delve down into the deepest bowels of your soul. Try to imagine the ultimate fucking nightmare. And that won’t come close to this sonuvabitch when he gets pissed.”

Elsewhere a handful of DEA/CIA/police bosses are suspicious of Seagal’s anti-authoritarian/loose cannon ways, but it has to be said that most people he comes into contact with can do little but stare in awe. It’s no surprise to see a crusading anti-drugs senator drop by Seagal’s house at the end of Law to thank him in person for his burst of carnage as a media throng waits outside for a penetrating insight into the menace of narcotics. In Siege an aging battleship captain takes the disgraced ex-SEAL under his wing, all but pleading to be a father figure. “If I had your ribbons,” he tells him, “I’d wear them to bed.” Later another navy boss labels him a ‘warrior’ and ‘the best there is.’

And so on.

Still, it’s Hard to Kill’s wannabe boyfriend Lieutenant Kevin O’Malley (Frederick Coffin) who takes the biscuit when it comes to Seagal veneration, especially after it’s believed the great man has been killed in the line of duty. “He had more honour and guts than this whole department put together!” O’Malley furiously informs one naysayer. When it’s realized the stupid doctors have erroneously declared Seagal dead, O’Malley is the first to tearfully hold his pal’s hand on the operating table and half-sob: “Don’t worry, buddy, I’m in your corner.” Over the next seven years the lovelorn O’Malley raises Seagal’s son, just waiting for that sweet, sweet moment when Seagal rises Lazarus-like from his slumber so he can finally be his pillow-biting wife in an ad hoc nuclear family. Sadly he never feels the warmth of Seagal’s lips, instead sacrificing himself to protect the man’s genetically superior offspring.

How often does Seagal beat up four heavily armed guys? Four appears to be Seagal’s favourite number when it comes to showcasing his fighting skills. In every one of his first six movies he simultaneously twats at least four guys, managing it three times in both Law and Marked. Justice might be the macho highpoint, though. After showily emptying his gun of bullets, he works his way through about eight guys in a bar. However, some opponents remain amazingly stupid e.g. one idiot in a trashed department store in Marked attacks him with a furled umbrella when anyone with even half a brain knows you need at least an Uzi to take on an unarmed Seagal. Perhaps further down the line (I haven’t seen his post-Deadly Ground fifty-odd movie appearances) he tired of using both arms and kept things fresh by gouging an eye with one hand while doing the ironing or washing up with the other.

Ludicrousness: You might find Seagal’s abundance of death-defying feats tricky to swallow, but I suggest his knack for evading automatic gunfire by dropping to the floor is yet further evidence of divinity. Ditto the way he turns the tables on those various mobs of tooled-up, would-be assassins sneakily arriving at his home. Plus, he instinctively knows driving a jeep will protect him, his passenger and its tires from a hail of bullets whereas if he’d chosen any other brand of vehicle he would’ve been fucked. For Christ’s sake, how else do you explain a beaten, heavily drugged prisoner fastened to a chair with cable ties not only breaking free but proceeding to whack all five armed assailants? No wonder Deadly Ground’s Michael Caine calls him the ‘patron saint of the impossible’, a comment that is merely a fancy way of saying miracle worker.

Nothing illustrates this better than Above the Law when he jumps onto the hood of a speeding car and ends up clinging to the roof. Despite the two goons inside both packing heat, Seagal makes the one run out of bullets (perhaps with the power of his mind) while the other repeatedly misses from six inches. Neither can they dislodge him, despite the speeding car weaving through midtown traffic. The best they can manage during a situation in which they appear to have complete control is a pithy insult in the form of ‘fucking animal!’

Unbothered, Seagal punches through the side window and reaches inside to employ an unbreakable throat grip on the passenger. The driver is so intimidated by this manoeuvre that he halts the car, enabling Seagal to hop off the roof and arrest them. I’m sure you’ll agree that if a mere human attempted this in real life, there might be a different result.

Another example of his uncanny abilities can be found in the accurately titled Hard to Kill. Here he takes a few bullets in the chest before spending the best part of a decade in a coma. His shaggy-haired, twitchy revival makes for great cinema, instilling the sort of reverie in the viewer that would surely be on a par with a true believer witnessing The Second Coming. However, perhaps it’s best to get a few things straight about his rapid recuperation. Yes, his ponytail survives unscathed. No, he doesn’t have a Dead Zone-like ability to see the future. Yes, it’s quite easy to tell the difference between his pre and post-coma acting. OK, I guess it’s a little more difficult to explain how he immediately escapes a trigger-happy assassin while supine on a gurney. Some non-disciples would point to this as a prime, groan-inducing example of Seagalian egomania. However, if Jesus can walk on water, then I have no problem with a groggy, horizontal, pyjama-clad ‘coma cop’ outwitting an experienced killer in possession of a silenced handgun and the full use of his body.

Bone-breaking quotient: You have to say that rearranging bones into balloon animal shapes is Seagal’s thing. Honestly, this dude treats a radius, ulna and tibia as if they are nothing more than twigs. Viewers don’t grasp this proclivity until the climax of Law during which he lovingly snaps the chief bad guy’s arm and neck. However, by the time Hard and Marked roll around, he’s very much into his stride. The former bloodily coughs up a broken knee, elbow, leg, two wrists and another neck. That’s quite a lot by anyone’s standards. Marked is perhaps the graphic, hyper-violent peak, complemented by the amputation of a gun-holding hand lyrically dropping to the floor. Seagal also crunches through an elbow, an arm, a neck, an elbow, a shin and a spine, spicing things up with a double eye gouge and a successful first attempt at decapitation. In both Justice and Siege he gives the musculoskeletal system a much easier time, delivering just a paltry broken wrist and a snapped arm. The big softy. Then again we do get an armpit stabbing and a torn-out larynx so perhaps not.

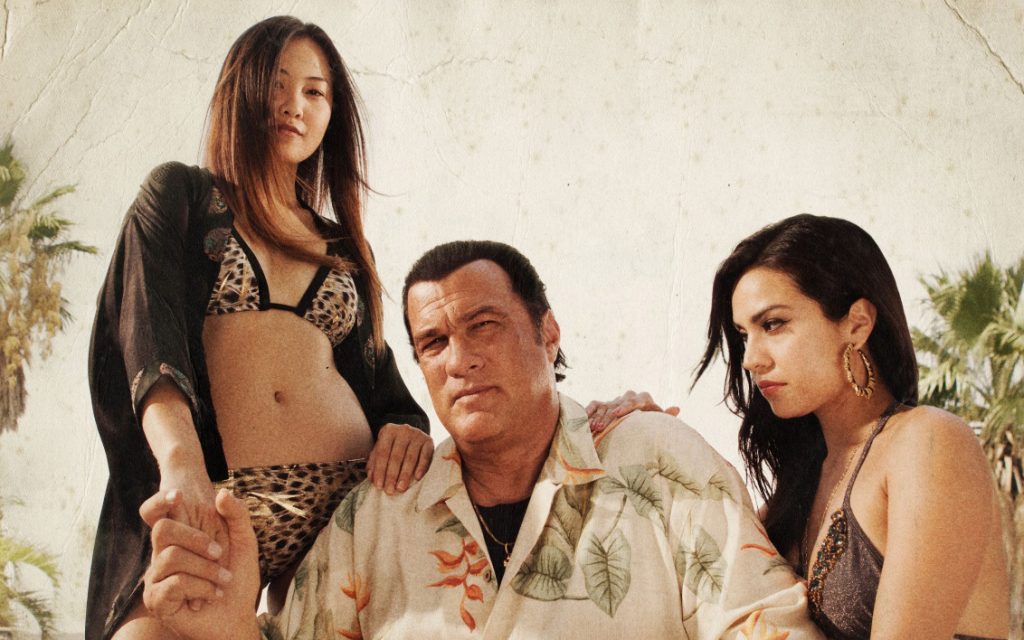

Women: As expected in Seagal’s red-blooded world, those lovely ladies don’t get the juiciest parts. Look at the way an upcoming Sharon Stone (with a hint of delicious puppy fat) is wasted in Law, saddled with a scared-wife-cradling-the-baby role. Ditto the still foxy blaxploitation star Pam Grier, who does little but change hairdos three times and get shot. The earnest, blank-faced Eskimo chick in Deadly Ground fares just as badly, reduced to interpreting, asking for explanations and following in Seagal’s shadow like the dumbest of Bond girls. Females essentially orbit him to make admiring comments, gyrate in states of undress, be protected and, of course, provide a reason to go on a self-righteous rampage.

In three of his outings, Seagal is married. Now it goes without saying that any lass who finds herself in the same room as such a knife-throwing deity is bound to be ecstatic, let alone one that has regular access to his trouser department. In Law and Hard both wives accordingly worship the ground he floats across, but there’s an anomaly in Justice in that his missus wants a divorce. Huh? How can any female seriously consider leaving Seagal? She must be deranged, a suspicion amplified when she dismisses the imminent male-on-male violence: “Why can’t you all just piss on a tree and mark your territory the way dogs do?” Later, however, (after her husband has racked up about twenty-five corpses) she’s won over by this expression of his tender heart and wants to reunite, telling him: “Everybody loves you.”

Amen, baby.

In Marked for Death Joanna Pacula plays a more intellectual type. Apparently she’s an authority on voodoo and Jamaican gang culture after having graduated from the Kelly McGillis Top Gun School of Absurd Roles. Despite her fondness for books and other non-sexual stuff, this doesn’t stop Pacula from getting smitten at the first sight of our towering hunk. After being told he’s retired from the DEA, she gives him the onceover and mutters: “He still looks functional to me.” Oh, Stevie boy, do you have any idea of your power? In Siege former Playboy centrefold Erika Eleniak is definitely less of an egghead, her embryonic brains having long ago migrated to her stupendous chest. She may evolve aboard a battleship from a woozy stripper into a gung-ho combatant, but she’s still a willing participant in a climactic snog that underlines Seagal’s virility.

However, in Hard to Kill it’s then real-life wife Kelly LeBrock (she of the lips and voice) who gives the most fascinating demonstration of Seagal’s lady-killing prowess. In a performance of supreme ridiculousness, she falls in love with an inert Seagal at the LA Coma Center before he’s woken up. “Would you like a little pussy?” is pretty much the first thing she asks before placing a kitten on his pillow. Excuse me, but are animals allowed in hospitals? Well, I guess the rules don’t apply when it comes to nurturing a bedridden beefcake back to bruising bravery. Neither, it seems, does professional etiquette given that she then lifts the sheets for a quim-moistening glance at his cock. “You’ve got so much to live for,” she says with unabashed longing. “Please wake up.” When her wish comes true, the first exclamation from her shell-shocked mouth is the somewhat unsurprising: “Oh, my God!” Yes, sweetie, God is back, and he’s once again keen to snap the arms of his children.

LeBrock spends the rest of the flick staring at Seagal’s handsome face while nodding at his constant flow of wisdom. Of course, it’s not long before she’s dressed up like a strumpet outside his room. “I was just passing,” she says while proffering a rose “and I thought you might like a flower.” Seagal takes it during a sultry burst of saxophone on the score, but there’s clear hesitation on his face, as if he knows he needs better scripts.

Does he cry or show any other unmanly weakness? There’s a scene in First Blood when Rambo (having destroyed a town among other things) wigs out in front of his father figure, Colonel Trautman. The more I think about it, the more I realize it’s unusual for such a macho action pic to depict its hero like a helpless six-year-old boy in a state of weepy incoherence. Some people snigger at such melodrama, but Sly’s wobbly disintegration does make sense after the trauma he’s experienced.

You don’t get anything like this in Seagal’s first six movies. The man is capable of expressing doubt (as he does about past behaviour in Marked for Death’s confession box) but crying jags aren’t his thing at all. Then again, as Seagal is not exactly known for the richness and fluidity of his expressions, it can be hard to tell what he’s feeling. Frequent bouts of constipation appear to be a good bet.

Still, there are moments when the steely exterior softens a tad. I swear there’s the briefest of scenes in Law where he thinks colleague Pam Grier is dead and his face is wet. In Hard to Kill (after banging Kelly LeBrock) he sits on the floor shaking his head while glancing at his wedding ring. No wet face this time, though. Nevertheless, he does pop along to his murdered wife’s gravestone to sink before it with both hands on his face. I believe he’s trying to convey grief, although he looks like he’s about to sneeze.

In Justice a tear rolls down his cheek while crouched in the street over the body of a slain buddy, although I think this has more to do with the oniony fumes of a nearby hotdog stand. Similarly he places a jacket over Siege’s murdered battleship captain, but you can tell he’s already inwardly rubbing his hands at the prospect of launching an all-out war against the terrorists responsible.

These spells of solemnity add up to a good eleven or twelve seconds of the near-nine hours of Seagal flicks I sat through.

Far Eastern or mystical bullshit factor: Martial artists are often guilty of espousing more guff than a back-peddling, crack-addicted politician. Bruce Lee’s films are littered with such groan-inducing shite e.g. listen to this crock he tells his mentor in Enter the Dragon: “A good martial artist does not become tense, but ready. Not thinking, yet not dreaming. Ready for whatever may come. When the opponent expands, I contract. When he contracts, I expand. And when there is an opportunity, I do not hit. It hits all by itself.”

Any idea what that means or how it’d help when up against a red-faced aggressor in a pub car park?

Thankfully, Seagal concentrates on busting heads while mostly eschewing such pretentious, yin-yang nonsense. In his early films there are snippets, especially in Hard to Kill where he seeks wisdom from a Chinese book before employing meditation and acupuncture to help him regain his pre-coma mojo. Eventually we see him restored to full manliness perched upon a rocky outcrop as a soaring eagle cries above.

Marked and Justice have no such mystical indulgences while Siege is only guilty of one bit of Bruce Lee guff when Seagal tells his nervous sidekick Erika Eleniak: “You gotta be invisible. If you walk by a hatch and you see the enemy, you become the hatch.” Mate, much as I love you, no one’s gonna mistake that girl’s rack for a goddamned hatch.

However, it’s the sledgehammer treatment of environmental woes in the Alaska-set Deadly Ground where Seagal loses his shit. This was his big chance to cement his Hollywood star, especially as he was handed the directorial reins for the first time and a budget of fifty-million smackeroos. Moviedom waited with bated breath. After all, God was about to direct himself.

Yet this heavy-handed flick, in which Seagal goes from a ‘cupcake’ to a ‘bear-man’, starts badly and rarely lets up on the mystical mumbo-jumbo during its first half. For example, after saving the ass of a bullied Eskimo pisshead from a desperately unconvincing bar bully, the rescued man reveals: “You are about to go on a sacred journey. This journey will be good for all people.”

Oh, gawd. I’d rather he just snapped limbs while terrified gangsters yelled: “I wouldn’t sell you the sweat off my balls!”

Seagal’s obnoxious, two-faced boss, the ‘dirty snow’ enthusiast Michael Caine, then tries to murder him, resulting in his recuperation in an Eskimo village that’s nothing more than an over-earnest exercise in gibberish. In his previous flicks Seagal was always the arrogant master but here he becomes a student, happy to absorb whatever quasi-religious bullshit the Eskimos sling at him. It’s pretty damn hard not to laugh when the tribal chief knocks him out with a feather, an action that drops him into the spirit world. Cue a cringe-inducing sequence of chanting, semi-naked, oh-so-wise indigenous folk, an eagle flying above snow-capped mountains, and a spot of bear wrestling. Regrettably, the animal doesn’t end up stabbed in the head with a corkscrew.

Any surprises? Not many, that’s for sure, mainly because Seagal insists on scripts presenting him as a combination of fierce integrity and triple hard bastard. He’s the same bullet-proof character in each movie. Only the length of his ponytail changes, although its mysterious absence in Siege is still a bit of a shock. I guess I would’ve liked some sort of explanation for why such a shining example of heterosexual manliness runs like a big girl, though. Perhaps show ponies can’t help but prance.

Above the Law qualifies as his most political film with its decidedly anti-CIA slant. “These guys have started and financed every war we’ve ever fought…” he says during an overcomplicated ninety minutes that takes in a Vietnam-era death squad, a whistle-blowing priest and a campaigning senator. “We’ve wiped out entire cultures. And for what? Not one CIA agent has ever been tried, much less accused of any crimes.” I don’t know about you, but I find such sentiment pithy. Shame Seagal didn’t pursue such anti-government schtick in his following five flicks.

Elsewhere, I always thought Jamaicans were dreadlocked, homosexual-hating, weed enthusiasts who lay around all day listening to Bob Marley whereas Marked for Death shows most of ’em have given up such sweet and gentle ways to bugger off to America to kill people.

Catch the straight-faced TV news reporter (who’s surely just wandered out of a Death Wish flick with her alarming crime stats) to hilariously tell us that more than ten-thousand Jamaicans are involved in drug trafficking across twenty states, an infestation of naughtiness that’s resulted in 1,400 murders in the last three and a half years. Cue scenes of innocent high school kids in Seagal’s neighbourhood being lured into crack cocaine addiction. This is an unacceptable breakdown in law and order, yes? No wonder the authorities don’t mind too much when Seagal, a retired DEA agent, starts massacring gangsters on the streets of Chicago. They clearly need all the help they can get.

However, it’s Deadly Ground’s aforementioned plunge into po-faced environmentalism that’s far and away the biggest surprise in Seagal’s early canon. Beforehand the only (piss weak) indicator of his reverence for nature that I could pinpoint was a contrived episode in Justice when he rescues a cruelly abandoned German Shepherd, hails himself an ‘animal lover’ and promptly kicks the puppy’s former owner in the nuts.

Entertainment value: Seagal’s movies are what I call Airplane Movies. This means they’re essentially time killers, entertaining enough if you’re stuck in the air for a few hours but short of artistic depth, decent characters and memorable dialogue. This doesn’t mean I look down on such fare because there’s nothing wrong with being entertained. Indeed, that’s the one thing I demand from a flick. Seagal mostly delivers in this regard, especially during the well-choreographed fights in which it appears he really is belting some of those extras.

Saying that, you can see why Seagal remained on the second tier of action heroes below the likes of Arnie, Sly, Gibson and Willis. They got to play Rocky, Rambo, the Terminator, Mad Max and John McClane, but Seagal’s script-picking failed to result in any iconic scenes or lines, let alone characters. Now you sure as hell don’t have to be a great actor to be a screen legend, but you do occasionally need to team up with an imaginative, risk-taking or disciplined writing team.

Still, things didn’t turn out too bad and for a while there he was riding the scarlet crest of a wave. I enjoy the coma-flavoured shenanigans of Hard to Kill, as well as the voodoo-tinged nasty violence of his third feature. I can’t really argue with the slickness of his Die Hard knock-off, Under Siege, either. It has lots of fun moments like an F16 getting knocked out by the dreadnought’s awesome defences before the villains toast each other with champagne to the mighty chords of Hendrix’s Voodoo Chile. Sure, Seagal might still be ruing his apparently heartfelt decision to stand behind that lectern in Deadly Ground, a career-maiming move that led to direct-to-video hell, but God has long had a reputation for doing things that beggar belief.

Or as Seagal says to a buddy in Marked for Death: “Since when did anyone ever accuse me of being sane?”