Some talented actors appear to have a bitch of a time choosing a worthwhile script. It’s almost as if a load is dumped in front of them, they close their eyes and pick one. Travolta’s a prime example, having appeared in nine thousand flicks but only a handful of classics since he first got going in the mid-seventies. Now I suspect there’s an awful lot of luck involved in ending up in a half-decent movie, let alone a topnotch one, but I assume doing your utmost to select a promising screenplay is the first step.

Actors are always walking a tightrope when it comes to signing on the dotted line, desperate to be in the next Pulp Fiction and nowhere near an Ishtar. Of course, there are a few mercenaries like the legendary madman Klaus Klinski, who’s on record as wanting the most amount of money for the least amount of work, but I’m sure the vast majority of thesps do their damndest to choose something good.

At his peak few could match Michael Douglas’ knack for getting his hands on quality, button-pushing fare. This was a man obviously attracted to thorny issues, the sort of stuff that prompted prime water cooler discussions. Sexual harassment, vigilantism, insider trading… Oh boy, he knew how to turn it into box office gold, not to mention get tongues wagging.

Now Kirk Douglas was a bloody tough act to follow, given the quality of Paths of Glory, Spartacus and Ace in the Hole, but I reckon Michael’s ability to fish out meaty, provocative scripts enabled him to surpass the old man’s achievements.

Coma (1978) & The China Syndrome (1979)

Douglas’ twenty-odd year run of plum cinematic roles got underway with the medical thriller Coma, playing the boyfriend of Genevieve Bujold. In truth, he’s second fiddle not only to our plucky heroine but the incredibly creepy central concept of turning the various internal bits of healthy patients into a lucrative black-market business. Douglas doesn’t do anything special, but he’s still part of a memorable flick with a couple of standout scenes.

Coma was a deserved hit, quickly followed by a project about a nuclear accident released less than two weeks before a real-life fuckup at a Pennsylvanian power plant. Now while I prefer flicks that depict full-on disasters to near disasters (coz, you know, lots of mangled corpses), this is still a worthwhile and admirably tense affair.

Douglas is a hotheaded TV cameraman, whose unappealing beard is matched by a wardrobe that includes everything from a flat cap to a tweed jacket with elbow patches. Dreadful. Anyhow, he happens to be doing a puff piece at a nuclear plant with lightweight reporter Jane Fonda when its core is almost exposed, a sphincter-loosening event that could have resulted in southern California being wiped off the map. He naughtily keeps filming the panic-stricken staff as they struggle to regain control, even though he’s been told any form of photography of the control room is a security breach.

Back at the TV studio the big boss won’t run his incriminating footage, prompting the memorable insult ‘chicken shit asshole’ before he starts lobbing around words like conspiracy. This still isn’t prime Douglas but he does get to label Fonda (who’s more concerned with hanging onto her good job than rocking the boat) ‘a piece of talking furniture’.

Fair play to the writers of Syndrome, they enable the viewer to follow the incredible complexities of a nuclear accident without boring us silly. It’s well-acted and has ongoing merit, especially as we’ve since had further radiation boo-boos at Chernobyl and Fukushima. Syndrome’s main function is to remind us we do occasionally need to think about Important Stuff, such as clean, green energy sources, before gleefully plunging back into cinematic worlds that are awash with bare boobies and bullet-ridden bodies.

The Star Chamber (1983)

“I got bodies piling up all around me and I’m passing out the ammunition.”

It’s fair to say Judge Steven Hardin (Douglas) is getting frustrated with the legal system. When he’s not being forced to let go baddies that shoot little old ladies in the head for their welfare checks, he has to release murderous child pornographers whose lovely handiwork makes seasoned cops throw up. Both cases fail because of ridiculous technicalities, leaving one of the alleged kiddy rapists to mutter: “God bless fucking America.”

All Hardin can do is bitch to his wife (“I feel like I’m on the wrong side”) and take his frustrations out on the prosecutors who aren’t properly preparing their cases (“You’ve hinged everything on a shaky search and dropped it in my lap. Terrific!”) Things continue to spiral downwards when he’s confronted by the outraged father of an adorable murdered munchkin and only able to proffer platitudes about the bind he’s in when it comes to the law’s rigid nature.

“What about justice?” the father counters. “You ever deal with that? Is that ever fed into this little crossword puzzle you call the law?”

The Star Chamber ensures it presents Hardin as a Bastion of Decency. He’s honest, good at his job, and supported by a loving family in his up-market home. We’re clearly supposed to view him as a right-thinking man, especially when he starts saying the system has been turned into a ‘giant Rubik’s cube that can be twisted into any pattern that fits’.

So what’s he gonna do?

Luckily, his older mentor Judge Benjamin Caulfield (Hal Holbrook) has a neat solution to this Dickensian the-law-is-an-ass problem. Hardin just needs to join the nine-strong ‘Court of Last Resort’, thereby helping arrange to have holes blown in any slimy criminal bastard who slips between the cracks.

As you can tell, The Star Chamber is a rightwing wet dream, the natural successor to pro-vigilante flicks like Death Wish in which glib, smirking scumbags finally get what’s coming to them. This is one bunch of fascist judges that even Dirty Harry would be happy to sit down with and shoot the breeze (or any passing perps). For the most part it’s simplistic, button-pushing stuff where the viewer is led by the nose into understanding, if not sympathizing with Hardin’s decision.

Or as the doubt-free Caulfield tells him: “Time to get your fingernails dirty, kiddo.”

Saying all that, The Star Chamber’s not a bad watch. It’s never dull and provides food for thought amid the killings. Douglas puts in a restrained performance, much more so than Pacino’s pissed-off, super-charged judge four years earlier in the similarly themed …And Justice For All. He does a lot of smoking and staring into space while wrestling with his tortured conscience, although he still gets to do some signature Douglas moves, such as pacing and banging things as his initially calm voice rises to a short, frustrated shout.

The Star Chamber runs with a fascinating idea and is given a professional sheen by director Peter Hyams. Shame it badly loses its nerve. Douglas would go on to make better stuff but any pic in which our refined and supposed betters hand out extrajudicial verdicts via an emotionless, silencer-equipped assassin is probably worth a look.

Romancing the Stone (1984)

This magnificent adventure-comedy was the start of Douglas’ golden age and the one in which his previous onscreen personas coalesced into a recognizable whole.

He plays the gruff Jack T. Colton, a rugged, self-reliant bird poacher in the Colombian jungle who only thinks about number one. He’s bumbling along quite nicely until the successful romantic novelist Joan Wilder (Kathleen Turner) inadvertently causes her bus driver to crash into Colton’s stationary jeep, resulting in fifteen grand of exotic birds flying away.

“Lady, you are bad news,” he tells her. “What’d you do? Wake up this morning and say: Today, I’m gonna ruin a man’s life.”

It’s telling, though, that the only object he rescues from his ruined jeep is a photo of a sailboat, a yacht he plans to buy and travel around the world in. Just like his newfound acquaintance, he’s a romantic, although he doesn’t know it yet.

In the meantime he needs to get rid of Joan, a hapless ninny who keeps doing stupid things like trying to recover a lost button in the dense undergrowth. Indeed, she’s the embodiment of a Ridiculous Girly, a cat-owning, dowdily-dressed dreamer in dire need of a damn good root to straighten her out.

Colton, however, is indifferent to this damsel in distress and does his best to abandon her, only changing his mind when a price is agreed for his help. I like the way she looks at her suitcase, obviously expecting him to act the gentleman and carry it, only for him to pick it up and drop it at her feet while passing her.

With its hair-raising escapades, such as a muddy water slide down a hill and a drive over a waterfall, this is an imaginative, fast-paced and well-executed movie. It’s got a good Lee Van Cleef-lookalike villain, excellent comedic support from Danny DeVito as an incompetent criminal, and a great romantic ending on a par with An Officer and a Gentleman’s Richard Gere sweeping Debra Winger off her feet. The unseen way Colton retrieves the titular stone from its reptilian guardian is beyond fucking pie in the sky, though.

Surprisingly, Stone also has a fair bit of edge. We get the odd rape joke, Colombia described as a ‘Third World toilet’, a stabbing, and blood spurting from the stump of a bitten-off hand.

Good-o.

Douglas makes a brash action hero, convincingly wielding a pump-action shotgun while also demonstrating a previously untapped flair for comedy. Best of all is the way he brilliantly meshes with Kathleen Turner, their joyous chemistry resulting in a further two outings together.

The Jewel of the Nile was the first, a mechanical flick I wish had started with a paunchy, balding Colton slumped in an armchair nursing a beer and watching baseball while his shrew-like missus bangs around the kitchen trying to calm their bawling baby. You know, a telling snapshot of how romance and sexual love inevitably disintegrate into drudgery and the possibility of murder.

Instead we get a charmless, contrived adventure built on the flimsiest of foundations. Poor Colton is pussy-whipped throughout, continually doing things he doesn’t want to do and obviously dreading the day he gets to meet the prospective mother-in-law.

I think there’s some sort of lesson to be learned here, guys.

Even though Jewel of the Nile sucked, it did decent business. With four hits under his belt Douglas was sitting pretty, but 1985 landed him with the equivalent of Cats. Now I haven’t seen A Chorus Line coz a Real Man has nothing to do with mincing musicals. Indeed, the last one I endured was the Oscar-winning Chicago, an unfortunate occurrence that can be explained by being in a state of extreme disorientation following several savage blows to the head in a street fight with at least four pensioners.

Anyway, Douglas’ Midas touch swiftly returned in 1987 when he starred in two blockbusters. Fatal Attraction was the first, a slick, plausible and intensely memorable thriller that’ll make any married guy think twice when offered frizzy-haired sex on a plate. Unfortunately, its melodramatic bathroom finale is so rotten I think I would have preferred Glenn Close getting stuffed down the bog or boiled on the stove. At least that would’ve been funny.

Then there was Wall Street.

Now I don’t believe anyone understands the stock market’s myriad financial complexities. I know I don’t. Shares, commodities, publicly owned companies, blue chips, the Dow Jones…

And, of course, given my near-total level of ignorance, I guess it was inevitable I invested a couple of grand in an Aussie telco back in the early 2000s. After six weeks I was a thousand bucks up, convinced I was the new Gordon Gekko. I even started wearing braces, a tie clip, avoiding lunch and contemptuously telling bemused passersby that if they wanted a friend to get a dog.

Then the share price of my beloved telco, my ticket out of the rat race, began falling. Not rapidly but steadily, an unspectacular decline that resulted in many pep talks with my reflection that usually went along the lines of Just hold your nerve, Davey boy, things’ll recover.

And did they?

Did they fuck.

Two years later my display of monetary verve had resulted in depression, a minor alcohol problem, the meek sale of the cursed stock for less than half my outlay, and the ongoing vandalization of any public telephone I happen to spot. To this day Wall Street remains a faintly traumatic watch as it’s a reminder of my own lack of stock market nous. I’ll never be a financial whizz-kid, just like I’ll never make a woman meow in bed. Saying that, Gekko is still one of the all-time great villains.

“Please allow me to introduce myself, I’m a man of wealth and taste…” So sang a deceptively languid Jagger in Sympathy for the Devil and that sinister tune always pops into my head whenever Gekko’s on screen. He’s a potent mix of God, Mephistopheles, Dracula and Scarface so it’s no wonder Bud Fox (an excellent Charlie Sheen) looks shit scared before his long-anticipated meeting with the ruthless kingpin.

Wall Street does a great job of building Gekko up. We first learn he’s a money-making machine who had an ‘ethical bypass’ at birth. Next there’s a glimpse of his beaming face on the front cover of Fortune magazine before a snatch of his authoritative voice is heard as subordinates troop into his office.

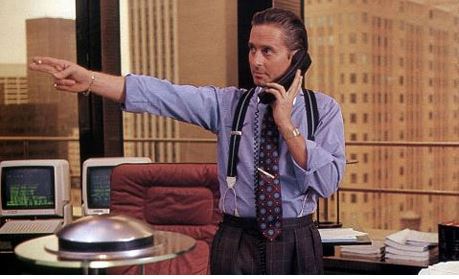

Our first meeting doesn’t disappoint. Sporting topnotch threads and slicked back hair, Gekko paces his humongous office barking orders down the phone at his minions. This is a man who radiates power, a perpetually hungry wolf in an impeccable suit whose steely gaze is always weighing everything up and seeing what’s in it for him. His single-minded commitment to the greenback is nothing short of fanatical.

The ambitious but wet-behind-the-ears Bud can do little but sweat and blunder in front of him, offering one dud financial tip after another. He knows his chance of gaining a foothold in Gekko’s seemingly unattainable world is growing slimmer by the moment until Gekko delivers the key line, the one that sets everything in motion.

“Tell me something I don’t know,” he says, which not only underlines the man’s insatiable lust for information but happens to be code for sell your soul, pipsqueak.

Poor Bud can’t resist, offering up inside info on his father’s airline company. Soon Gekko has taken Bud under his leathery wing and is schooling him in the dark arts of fiscal maneuvering. He doesn’t value hard work or persistence; it’s all about pertinent info. “If you’re not inside, you are outside,” he tells his new protégé. “I bet on sure things. Read Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. Every battle is won before it’s ever fought.” Gekko’s language is full of violence, littered with references to war, fighting and slaughter.

He’s also a two-faced liar, a relentless man who will pose as your friend in public and private while all the time sharpening his fangs to sink into your jugular. With his devilish grin, he loves stripping a company’s assets in the same way he enjoys pulling the clothes off a piece of top quality ass on his private jet. It’s all about conquest, you see, planting his flag on top of whatever’s wreckable.

Not that he can’t defend his corner.

“I am not a destroyer of companies,” he publicly tells the shareholders of a company he’s about to destroy. “I am a liberator of them. Greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms, greed for life, for money, for love, for knowledge has marked the upward surge of mankind.”

Bud is bewitched, hopelessly corrupted by his shiny new baubles and unable to see that a driven, obsessive man like Gekko is actually ill. Maybe he might understand if he were privy to some of Gekko’s more nefarious remarks. How about this doozy to Bud’s high-class new girlfriend, a woman he’s long had under his duplicitous control: “You and I are the same. We’re smart enough not to buy into the longest myth running: Love. A fiction created by people to stop them jumping out of windows.”

Oh God, isn’t Gekko great? He’s got all the answers, except to the one question at the root of it all: How much is enough?

On the face of it, the superb Wall Street is the story of Bud’s rise and fall in a frantic, dog-eat-dog world. Sheen is very good, especially the way he blubs at work after unleashing the Kraken on his principled blue-collar father, literally breaking the man’s heart. However, this is Douglas’ best-known role and for good reason. He’s an absolute powerhouse, dominating the avarice-fuelled proceedings like Anthony Hopkins in Silence of the Lambs and Orson Welles in The Third Man.

And remember, kids: “It’s all about the bucks. The rest is conversation.”

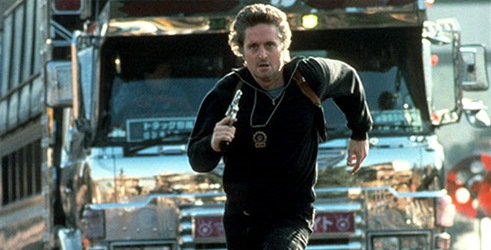

Some flicks fall into the category of what I call Airplane Movies. They’re watchable at 35,000 feet, but have pretty much left your head by the time you’re standing at the baggage carousel vaguely disappointed that you once again never got a sniff of joining the Mile High Club. Black Rain, much like Ridley Scott’s later American Gangster, is a classic Airplane Movie.

After the dizzying highs of Fatal Attraction and Wall Street this one has to go down as a disappointment, especially as Douglas was at the zenith of his powers. Surprisingly, it’s the first time he played a cop since his Streets of San Francisco days on TV back in the 70s. However, although I don’t care for Black Rain, perhaps its main merit was providing Douglas with the blueprint for Basic Instinct’s turbo-charged Nick Curran three years later. Practice makes perfect and all that because the similarities between the two characters are remarkable. Both are gruff, macho loose cannons, in trouble with Internal Affairs, hate rules and procedures, have an ex-wife, smoke like shit, and get involved with a blonde hottie who knows how to fill a dress. They even share the same first name. The chief difference is Basic Instinct’s Nick Curran sports a less embarrassing haircut as he hunts his AC/DC quarry with a permanent hard-on.

So why is Paul Verhoeven’s controversial, balls to the floor thriller ten times better? Well, Black Rain has an irrelevant beginning, weak foundations, by the numbers plotting, some groan-inducing implausibilities, and a so-so cast. It’s not dull, but there’s no verve, no razzle-dazzle, no oomph. Douglas plays the dick-swinging Nick Conklin, who happens to be in a restaurant with his eminently reasonable partner Charlie Vincent (Andy Garcia) when a Jap gangster Sato (Yusaku Matsuda) kills two other baddies in front of fifty horrified witnesses. Despite catching him after a chase and a bit of fisticuffs, the US authorities bafflingly decide to return Sato to Osaka. On the trip over there those butterfingers Nick and Charlie allow Sato to be whisked off the plane by his own gang members posing as cops.

I have to say it’s a rushed, if not plain daft setup.

Nick gets the odd decent line (“Sometimes you gotta forget your head and grab your balls”) but the lightweight Charlie provides bland support, especially when compared to the excellent George Dzundza in Basic Instinct. “Ladies of the eighties are going for shoes,” Charlie chirps at one point, a fair indication of his lack of decent lines. Please cut this man’s head off. Similarly, the spiky-haired, shades-wearing Sato is no match for Sharon Stone, particularly in the tit department.

Not much is made of the culture clash, either. In one brilliantly original scene, we discover Nick’s not very good with chopsticks. Given how impulsive (‘Fuck patience!’) and unreconstructed he is, there’s a disappointing lack of racial aggravation and non-pc slurs thrown around. Nick says ‘nip’ once and even then he thinks the guy he’s disparaging won’t understand. Likewise, the straight arrow Jap cop (Ken Takakura) he chafes against is similarly unimaginative in his insults. “Perhaps you should think less of yourself and more of the group,” he tells Nick while trying to remove the rod from up his ass. “Try to work like a Japanese.”

Yes, very level-headed, clap clap, but hardly memorable stuff.

Tellingly, Black Rain’s best bit has nothing to do with the routine action and uninspired dialogue. It arrives at an outdoor eatery when the straight arrow cop asks Nick if he’s guilty of taking dirty money back in New York. Nick, having earlier raged at Internal Affairs that he’s clean, simply stops eating his noodles and looks down. “I’m not proud of it,” he says with unexpected candor and contrition. “I had a divorce, kids, bills…”

It’s the only moment in this Airplane Movie that emotionally connects.

The War of the Roses (1989)

I’m a loner and have been all my life, although I did once live with a woman. Well, I say ‘live with’ but the truth was more to do with tolerating her company under the same roof as she paid the rent. It was an uncertain period in my life so the functional arrangement and occasional fuck suited me fine, but when she bafflingly started dropping hints about marriage and babies I was gone before the accusation ‘user’ could be spat out.

To this day I have no idea why people get hitched and/or reproduce. Seeing the same person pretty much every day of your life? Being tied to an ungrateful kid or two for a couple of decades? Christ, why would anyone go in for such irritating, restrictive and damaging nonsense? Please provide some proof that people are meant to be together for a long period of time.

That’s why I have a sly fondness for War of the Roses, a bitter, savage depiction of a collapsing marriage. Look what I avoided, I always think when the credits roll. Doesn’t Davey know best?

Then I have a smug wank to celebrate my profound loneliness.

Oliver Rose (Douglas) has been married for eighteen years to Barbara (Kathleen Turner) and they live in a mansion. To the outside world they’re a hugely successful couple but it’s not hard to see their relationship is filled with mind games, sarcasm, passive-aggressive bullshit, deeply irritating mannerisms and habits, the exhausting need for diplomacy in the face of the ever-present threat of conflict and the continual headbutting involved in trying to establish once and for all WHO’S IN FUCKING CHARGE.

You know, just like any other couple.

Everything comes to a head when Oliver painfully experiences what he thinks is a life-threatening wobble only to find his wife doubling down on not coming to the hospital by asking for a divorce.

Why? he asks.

“Because when I watch you eat, when I see you asleep, when I look at you lately, I just wanna smash your face in,” she replies before punching him.

Fair enough.

They say all wars are fought about territory and Roses brilliantly encapsulates this in a microcosm as the pair rapidly descend into an unholy battle over who gets the house. Before long they’re trading insults on the stairs, throwing crockery and destroying property. Cats and genitals don’t fare too well, either.

“You have sunk below the deepest layer of prehistoric frog shit at the bottom of a New Jersey skunk swamp,” Oliver tells Barbara in a divorce lawyer’s office. He’s actually the sympathetic character here, although he’s happy to land the odd low blow. Take his standout scene when he drunkenly arrives home as Barbara hosts a black tie dinner party for her business clients.

“I would never humiliate you like this,” she says while he stands on a chair in the kitchen pissing on the fish.

“You’re not equipped to, honey,” is his priceless retort.

Douglas and Turner rekindle their chemistry in Roses, a deranged, take-no-prisoners black comedy which memorably illustrates the dangers of digging your heels in.

Or at least sawing them off your wife’s shoes.

Basic Instinct (1992)

In a Hollywood first, Nick Curran is a cop on the edge.

Not that you can immediately tell. On his way to a murder scene, he’s well-groomed, asks questions in a measured tone, and looks like he’s got it together. Yes, he has a penchant for inappropriate remarks, but we’ll forgive him as he no longer drinks, smokes, snorts coke or shoots dead hapless tourists.

Then he gets dazzled by a flash of Catherine Tramell’s (Stone) vulva and goes off the deep end.

Now I know she’s got a degree in psychology, but it’s still amusing how fast she messes with the inside of his head (“Have you ever fucked on cocaine, Nick?”) In two meetings flat he turns into the equivalent of a horny werewolf with a badge. Suddenly he’s swigging Jack Daniels again, chain-smoking, publicly threatening to ‘kick the fucking teeth in’ of a goading member of Internal Affairs, and virtually foaming at the mouth.

Not to mention slamming the psychologist assessing his wellbeing (in the wake of the aforementioned tourist shootings) up against a wall, tearing her blouse open and bending her over a couch during an ass-baring display of rape.

“You’ve never been like that before,” she says while numbly gathering up her ripped clothes. “Why?”

“You tell me,” he replies with a shrug. “You’re the shrink.”

Jesus Christ, what’s he gonna do if he gets to spend any more brain-scrambling time with Catherine? Have a go at bestiality? Walk into McDonald’s with an AK47? Try to get New Kids on the Block to reform?

Whatever the case, Basic Instinct’s first forty minutes provide the perfect evidence for Douglas’ willingness to take on less than saintly roles. I mean, could you see a fellow A-lister like Tom Hanks doing something as fantastically in your face as this?

But hang on, Nick’s not finished yet. My god, his pussy-pickled brain is now telling him it’s OK to wear a V-neck green sweater sans shirt in a nightclub. Somehow Catherine thinks this is acceptable foreplay and they finally get it on. During sex, Nick looks like he’s losing his mind, trying to be the boss with some manly thrusts but ending up tied to the bed. Is she going to whip out her favorite murder weapon and treat him like a giant human ice cube?

Nope.

Instead she rides him to ecstasy before releasing him from his silky bonds, his evident relief resulting in him embracing her like she’s his mum. Honestly, this is fucked-up stuff.

However, it gets even better.

After padding nude to the luxurious bathroom, he delivers a fantastic line to Catherine’s lesbo lover, Roxy, who’s been secretly watching their nuclear-powered humping. Without attempting to cover himself up, he just looks at her. “Let me ask you something, Rocky, man to man,” he says, deliberately getting her name wrong as his voice drips with smugness and contempt. “I think she’s the fuck of the century. What do you think?”

He then gets back into bed with the game-playing Catherine. When she wraps his arm around her and meekly kisses his hand, he obviously thinks he’s tamed the tigress.

Douglas would never be this brave again. Sure, he’s overshadowed by Stone’s feral, star-making turn, but he’s still fucking great in Basic Instinct, one of the most astonishing, full-on movies Tinsel Town ever pumped out.

Falling Down (1993)

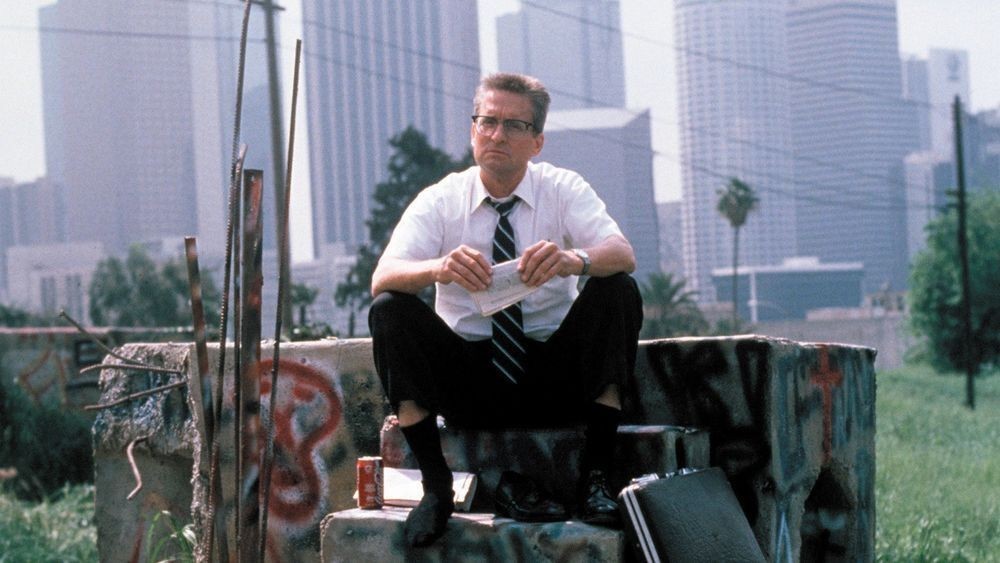

Fuck knows how you follow something as jaw-droppingly provocative as Basic Instinct but Douglas managed it with this bloody fantastic urban dystopia. This is the one where he’s got the military-style haircut, the glasses, a perfectly understandable penchant for pointing a pump-action shotgun at garishly dressed golfers, and a simple, but overwhelming desire to get home.

Except, of course, in this case home means death.

I must say I do love this flick’s beginning, a near-wordless five minutes which demonstrates how simplicity can sometimes be gold. We meet a sweaty, fly-bothered Bill Foster (Douglas) marooned in a ghastly traffic jam during the rising heat of the morning rush hour. His tie is rammed up to his throat. There’s not enough air and what he can get into his constricted lungs is tainted by exhaust fumes. There’s nothing to do except listen to shrieking school kids, look at dumb bumper stickers and hate people. You can almost hear the needle-like thoughts jabbing his feverish brain: Is this what it’s all about? And I fucking do this five days a week?

Questions, no doubt, that many of us have asked at one time or another. We’re fully on his side at this point. He’s mad as hell and he’s not gonna take it anymore. Having reached boiling point, Foster pushes open his car door and steps out. He might be carrying a briefcase but that accessory soon proves little more than the most superficial of attempts to present a civilized front. In essence, from this moment on he’s walking in ever decreasing circles toward a landmine.

But what an incident-packed journey across a God-awful inner-city landscape crammed full of hustlers, beggars, placard-waving protestors, yet more road works, overcrowded buses, giant advertising billboards, the homeless, uncooperative fast food managers, knife-wielding would-be muggers, abusive drivers, and homophobic, nigger-hating white supremacists. Basic civility is at a premium. Graffiti and gaudy street art are everywhere. Sure, there’s some clumsy exaggeration of LA’s inhabitants to the point of cartoonish excess, but I still love director Joel Schumacher’s dysfunctional vision of stifling heat, stressed individuals at breaking point and a prevailing lack of courtesy.

What’s also clear is the significance of territory. Time and time again Foster encounters people trying to eject him from their turf. Gang members, shopkeepers, construction workers and golfers all instruct him to leave. Hell, even the mother of his little girl doesn’t want him anywhere near his former home. This is a guy who might be in motion but in reality has nowhere to go. He’s a middle-aged man wearing worn-out shoes and sleeping in a single bed, silently sharing strained meals with his scared mother. He has no job, no family, no function. A man out of time. No wonder he compares himself to a stranded astronaut on the dark side of the moon.

“I’m past the point of no return, Beth,” he tells his ex-wife on the phone. “Do you know when that is? That’s the point in your journey when it’s longer to go back to the beginning than it is to continue to the end.”

You’ll never hear the rationale for murder-suicide put better.

Still, there are some brilliantly funny scenes along the way that capture modern life’s intensely annoying facets, especially the fake chumminess of retail staff and their rigid adherence to pointless policies and schedules. Who doesn’t want to pull out a semi-automatic weapon when faced with such pinheads? And aren’t we naughtily on Foster’s side when an outraged, privileged golfer shouts ‘Fore!’ and drives a ball at his head only for him to yell ‘Five!’ and start blowing holes in the man’s stupid electric golf cart?

Foster, whether massaging an ice-cold, overpriced can of Coke against his face or complaining that the burger he bought looks nothing like the one in the photo, is the most memorable consumer rights advocate you’ll ever meet.

Don’t go thinking he’s a victim, though, or that the brilliant pacing of the over the top Falling Down condones his attitudes and actions. He’s simply an abusive, dangerous man floundering on a scrapheap. However, Douglas in meltdown mode is riveting from start to finish. It might just be his best movie.

Disclosure (1994)

Back in the 90s I used to be a newspaper reporter. I covered a lot of court cases, a fair chunk of which was sex stuff. My paper got wind of a guy employed by the cops who was up for sexually assaulting a colleague. He was a paper shuffler, rather than an actual police officer, but reporters love the whole idea of anyone remotely connected to law and order doing naughty stuff.

Anyhow, I covered the first day of his trial and couldn’t believe the prosecution’s piss-weak opening statement. Basically, the guy had brushed up against a colleague at work but insisted it was inadvertent. No dick out or tit grabbing or lewd remarks or sustained campaign of harassment or anything. I can remember thinking poor bastard and that the case should never have got to court as no jury in their right mind would convict on such feeble evidence.

I happened to be on holiday for the trial’s second day, but when I returned to work the guy in question phoned me all upset. Turned out he’d been cleared midway through the second day but the paper hadn’t sent anyone in my place to cover it. He wanted to know where the story was proclaiming his innocence.

Well, I didn’t have an answer for the news desk fuckup, but I do remember his acute distress at firstly being accused of sexual harassment and then being the subject of front-page prominence. He made it clear it was a ghastly, life-altering process with some people muttering all the way that there’s no smoke without fire. Innocent until proven guilty means jack shit in the real world. Or to use another metaphor: Mud’s easy to sling and it sticks good.

These days things have probably got worse, especially with the internet’s arrival and the prevailing narrative that men are bad. Victims are routinely believed, no matter how old or flimsy their claims, and very few observers seem to consider they might be attention-seekers, avaricious, back-stabbers or malicious liars. Indeed, the media can’t get enough of such reputation-destroying stories. Sure, it’s still easier to be a man than a woman and a certain percentage of men are predatory shits, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t some dark sisters out there willing to use changing times to their advantage. After all, women are human and we know what those fuckers are like.

Disclosure plunges headlong into such incendiary material. It’s definitely one of Michael Douglas’ hot button masterpieces, a flick that remains scarily relevant when it comes to the fractious nature of male-female workplace relationships. This is a nuanced, thought-provoking and deeply uncomfortable watch.

Douglas plays Tom Sanders, a former playboy turned Fatal Attraction everyman. He might’ve ‘seen more ass than a rental car’ but those days are long gone. Now he’s settled with a loving wife, two cute kids and a nice home. He’s also in line for a prestigious promotion at the tech company where he’s worked damned hard for the last decade.

However, there are a couple of troubling signs. For a start his wife says: “Grandma used to have this expression: Don’t climb up too close to God. He might shake the tree.” Then a laid-off IBM worker tells him on the ferry he catches to work that he was earning one hundred and fifty grand a year before being ‘surplussed.’ Both comments suggest how quickly things can change, how you can go from riding the crest of a wave to being dumped in a cesspit.

When Tom arrives at the office he catches a glimpse of a pair of bare legs going up the stairs and pauses to admire the swaying ass on top of them. It’s not intimidatory or creepy, it’s just an involuntary, healthy appreciation of the female form. He’s a regular, red-blooded guy, all right.

Then he swats his attractive secretary’s bum with a handful of manila folders. There’s nothing even remotely sexual or power-based about it and she doesn’t complain, but it’s the first suggestion he might not be the most enlightened employee.

Tom, however, has more pressing things to mull over as news filters down that he’s missed out on his long dreamed-about vice-president promotion. The job’s not only been ‘stolen’ by an outsider, but given to an ex-flame by the name of Meredith Johnson (Demi Moore), a highly sexed woman he used to watch porn with, sodomize, bang in public places and use a dildo on. At a team meeting his male subordinates suggest she only got the plum job because she’s attractive and sleeping with the big boss while the solitary female in the room rolls her eyes. “All I know is any woman has to be twice as good as a man and work twice as hard to get the same job,” she says.

The first shot we get of Meredith is a closeup of her shapely calves ending in black high heels as Tom passes by in the background, an unquestionably sexual piece of framing. Is he going to end up skewered on one of those alluring spikes? She invites him up to her office for an after-work drink, saying: “I remember how you liked a good bottle of wine. I’ll get one.”

During the subsequent meeting, which I’d argue is a classic scene of 90s cinema, the role reversal already hinted at is played out in full. I love how Meredith sits and pats the space alongside, indicating for him to park his cute little butt next to hers. “I like all the boys under me to be happy,” she says before hungrily running her eyes over him and belittling his nourishing domesticity. “You’ve kept in good shape, Tom. Nice and hard.”

Christ, it’s fascinating upside-down stuff. Not long after asking him to massage her shoulders she launches an aggressive, cock-rubbing raid as he does his best to protest. “Why don’t you just lie back and let me take you?” she pants. “I could’ve had anybody and I picked you.”

Tom manages to abort the subsequent blowjob but when she starts pushing her finger into his mouth, he kicks against his submissiveness and finally becomes the ‘man’. Tom’s no saint here as he rips her blouse open and knickers off, but when he catches sight of his demented face in the window he comes to his senses and stumbles out of the office with telltale scratch marks down his chest.

“You get back here and you finish what you started,” she yells after him. “You hear me? Or you’re fucking dead!”

Wow. What a bloody great scene. Bold, graphic and a long way from black and white, but it’s still clear the entitled Meredith has abused her power as his new chief. On top of that I’ve got so used to seeing Michael Douglas bossing others that it’s a real eye opener to catch him in a passive role, eventually fleeing from a woman with his tail between his legs. Indeed, he spends most of the movie in a state of extreme discomfort as the poison of her ensuing sexual harassment claim spreads.

And fair play to Demi Moore, she nails her role as a ruthless, power-hungry corporate cow. Now I don’t usually care for her (bloody hell, have you seen Striptease and G.I. Jane?), but she has her uses (A Few Good Men) and she’s superb here. Every scene with Douglas is a corker. Meredith’s a shell of a person, some sort of frightening prototype, a cold, humorless bitch, and ambitious for ambition’s sake. I suspect if you scraped off her perfectly applied makeup you’d find cancerous sores. In the classic 70s movie Network Max Schumacher (William Holden) rips Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway) apart by ramming home the ‘shrieking nothingness’ of her existence. Well, Meredith’s the personification of shrieking nothingness, a status-obsessed woman who must win at all costs. There’s no love in her, no warmth, no joy. Her only claim for sympathy is that these days women know they’re supposed to be assertive both in the workplace and in bed, a seismic shift that rejects motherhood and perhaps forces some of them to ape the aggression of men.

Meredith’s teary, pale-faced recollection of her sexual encounter with Tom during the subsequent in-house mediation is nothing short of compelling. It’s amazing how we know she’s a bare-faced liar yet she still seems more credible than the flustered Tom, who has to recount the sordid events in front of his angry, humiliated wife. And who can forget Meredith smugly standing in an elevator as the doors ping open in front of Tom only for her to say: “Going down…?”

This is a prophetic movie, chock full of snippets of dialogue that illustrate how the male-female pendulum has swung (as it needed to do) but is now more like a wrecking ball. I suspect men have grown intensely wary of working women (both above and below them) because it’s clear anything can be twisted. A remark, a laugh, a non-verbal gesture, a shared history or even a gift can all play their part if there’s a spiteful agenda to be served. An argument becomes verbal abuse, raising your voice is bullying, an overheard private remark is harassment, and a passing comment or a shoulder touch becomes inappropriate.

And sexual contact? Oh, boy. That sort of thing can be flipped as easily as a particularly rotten egg.

After Disclosure Douglas’ ability to pick edgy scripts noticeably tailed off, resulting in so-so efforts like The Ghost and the Darkness and Wonder Boys and an outright dud like Don’t Say a Word. Yes, 2000’s Traffic was a bloody great ensemble piece, but his conventional performance within it as a newly appointed drug czar whose straight A teenage daughter becomes a junkie smacked of contrivance.

Not that his decline into more standard stuff mattered too much. With a Best Actor Oscar under his belt, numerous iconic roles, and a clear hatred of blandness, what did he have left to prove or achieve anyway?