There are many people who like to grapple with the Big Questions, such as whether we’re alone in the universe, what happens after death and what celeb has the best tits. Luckily I’m in a position to answer the last one in that God has the best tits because (a he’s Perfection so it stands to reason he’s gonna blow the likes of Sharon Stone outta the water and b) I’ve got a lovely pic of his juicy rack courtesy of a paparazzi mate. I might even slap it up on EBay. Gotta be worth more than a porridge stain on a tablecloth that looks like Jesus’ lovely beardy face.

Anyway, to return to my original point, some of us do seriously contemplate life’s profundities, especially the pressing need to identify the best ever gangster flick. This is damn easy when it comes to the Yanks, the general consensus being Godfather sits at the top of the bullet-ridden tree followed by its sequel and Goodfellas.

Yes?

Now you might disagree, but I’d rather not storm round your house, stick your head in a vise and start yelling as I tighten the jaws: “You’re wrong! No way’s Casino the best! It’s a sub-par retread of Goodfellas!”

However, declaring a British winner is not so straightforward, even though there are only two contenders. In fact, it’s nigh on impossible for my little brain to separate the icy brilliance of Get Carter from the operatic majesty of The Long Good Friday. Indeed, if I had to explain the enduring magic of the movies to a non-acolyte, some weirdo who preferred computer chess or having sex, I’d simply fling these two treasured DVDs at their lamentably ignorant head.

Hand on heart, I’m not joking when I say I’ve lost decades trying to work out whether Friday is better than Carter or vice versa. Believe me, the routine failures of my intimate relationships, as well as my lowly position in life, are mostly down to the innumerable hours I’ve spent wrestling with this cinematic conundrum.

It’s especially galling given that my analytical methods have always been sharp and beyond reproach. Sometimes I keep a meticulous note of how many times my dog, Nigel, wags his tail during back to back viewings. Other times I consult Jesus on my porridge-stained tablecloth. And sometimes, when I’m really desperate, I seek out the opinions of knowledgeable fans or turn to books by respected writers.

The result? A goddamned dead heat every time.

Nonetheless, in one last Herculean effort to put this torturous but vital matter to bed, I’m proudly offering a near-scientific breakdown of each movie’s key areas that I’ve just stolen from Nigel.

Woof! Woof!

WARNING: 100% SPOILERS

The Preamble

At the start of The Long Good Friday there’s been no gang trouble in London for ten years. Top dog Harold Shand is not simply content to rule his turf with an iron fist, though. Oh, no. He’s in the final stages of legitimizing The Corporation by sealing a mega-money deal with the New York Mafia to develop the London Docklands, a prime real estate site which will eventually become home to an Olympic stadium. Harold is articulate and intelligent, a patriotic man and proud Londoner with genuine vision and ambition who sees Britain as a leading European state. He wants hands across the ocean, but just when it looks like everything’s sweet, his crime empire comes under attack from an unknown assailant.

Jack Carter is also a violent London gangster, but he shares few other similarities with Harold Shand, apart from a penchant for a dapper suit. He’s not a crime boss, obviously lacking the requisite skills for any kind of management. This man’s a lone wolf, someone who simply must find out what happened to his dead brother, Frank, in Newcastle, a city he long ago fled for the bright lights of the capitol.

Like Friday, the action takes place over a very short period of time. It’s a revenge thriller, but it’s terrific characters and labyrinth plotting mean first-time director Mike Hodges’ very confident handling steers it away from simplistic, predictable nonsense.

Carter was faithfully based on Ted Lewis’ Jack’s Return Home, a brilliant 1970 novel that presents a vivid world of unreconstructed males while also fleshing out Jack’s tremendously fucked-up relationship with his brother.

The Opening

Friday begins with a series of largely dialogue-free vignettes. We get a country farmhouse, a suitcase full of cash, someone on the take, and a semi-automatic rifle being poked through a window. There’s a gay guy hooking up in a pub, some sort of abduction, and a couple of bodies being dumped by the roadside before we switch to a widow in black at Paddington Train Station overseeing a coffin’s arrival.

All in all, it’s a classic case of show don’t tell, although we sense we’re in a world of men. It’s a little murky, but Friday’s jittery start credits the viewer with both intelligence and the patience to find out how the events are connected. In short, it sucks you in just fine.

The start of Carter is much simpler. We first see Jack Carter at night framed in a bay window with his hand in a suit pocket and the other holding a glass. Clearly something’s on his mind. As he turns, we hear a snatch of howling wind. Then there’s the flare of a projector and male laughter, the sort of sniggering that suggests something naughty’s being watched. Carter’s now sitting on a couch, obviously not in the moment, as the others giggle over a black and white porno slide show joking about pythons and contortionists.

“Bare arse naked with his socks still on?” one says. “Yeah,” comes the reply, “they do it like that up North.” With the first bit of dialogue we get a contemptuous reference to the North. Carter remains silent, even when someone refers to it as his ‘old stamping ground’. There’s the first close-up of Carter’s surly face in the gloom. Then there’s a glimpse of a cigar-smoking boss stroking Britt Ekland’s stocking-clad thigh, her beautiful face suggesting she’s not enamored.

Carter stands to top up his whiskey. “We don’t want you to go up North, Jack,” the boss says. “No?” Carter tersely replies. It’s fitting that the first word Carter utters is negative; something the other party doesn’t want to hear. He’s told the Newcastle mob are ‘hard nuts’ and that the police seem satisfied. “They won’t take kindly to someone from London poking his nose in.”

And with this nugget of information we know we’re watching a man on a mission movie. We cut to a shot of a train speeding into a tunnel, a perfect metaphor for a plunge into darkness.

This is a great three-minute opener, concise and clear. Carter is terse, sullen and restless. Nearly sixty words are spoken to him, but his replies total just fourteen. Even so, he manages to communicate an amazing raft of information about his character and mindset. It’s clear he doesn’t recognize authority, keeps his cards close to his chest, and obviously doesn’t care about the feelings of others. It’s not revealed what Carter needs to do up North, but we’re already certain he’s gonna play hard ball to get it.

Winner: Carter

Music

Friday’s main theme, composed by Francis Monkman, roars into life over a black screen before any images appear. Rightly so. This is one of the most distinctive scores of all time, up there with Jaws and Good, The Bad. It’s a galloping, gargantuan piece of music that’s simply drop-dead amazing, although some nitwits have been known to complain it’s crass, intrusive and dated.

What the fuck?

Now I don’t have the chops to properly analyze music, but I do know Friday’s signature tune utilizes a fusion of electronica, synthesizers and rock. Every time it fires up it infuses me with energy, making me snarl, dementedly play an imaginary instrument and fucking well groove. To be honest, its effect is a bit embarrassing. However, the way it drives the movie’s big moments, along with some searing strings, is awesome.

This main theme routinely gives way to stripped down versions before powering up again. In fact, it continually swells and fades throughout, like my cock whenever I drunkenly loiter outside a convent. The quieter moments effectively generate suspense. They throb, thrum, murmur and shimmer, as if nudging the viewer and saying: Hang in there, son, something’s gonna go fuckin’ mental in a minute.

Friday remains the only soundtrack I’ve ever bought (although if I’d known little Bobby Hoskins was gonna sing on one or two tracks I might well have hesitated). Still, at least he didn’t do a cover of Friday on my mind.

In contrast, there’s barely any music in Carter. The sparse opening motif, which accompanies Carter’s train journey north, is a mixture of harpsichord and piano. It is really cool though, returning at the end.

Winner: As you can probably guess, Friday by a country mile.

Locations

Friday boasts a huge variety of settings from a well-attended cathedral service and heaving backstreet boozers to a marina and up market restaurants. Locations constantly change, seamlessly mixing the classy and rundown. Oh, and let’s not overlook its fantastic use of an abattoir as Harold wrongly strings up his fellow gang leaders in a bid to finger his tormentor.

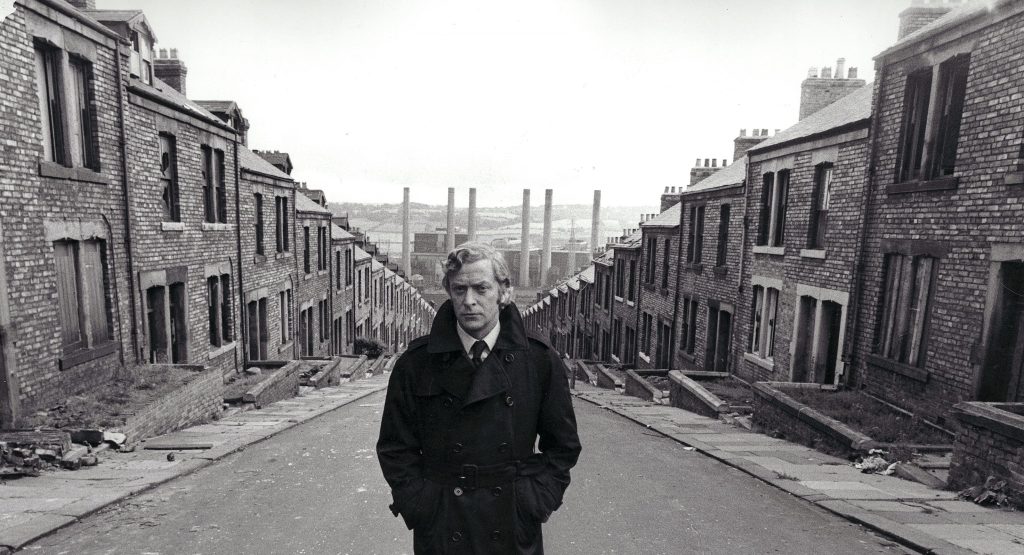

Carter, however, stays entirely within one place: Newcastle. This large English city used to be a boom town, but by the early 70s its mining and world-renowned shipbuilding industries were falling apart. Hodges takes full advantage of its decaying nature and makes brilliant use of location, rivaling Rocky in the way the slums of Philadelphia are presented.

He relentlessly mines this rich seam of rot, giving us a grim landscape of grotty boozers, wrecking yards, bookies, iron bridges spanning the River Tyne, alleyways full of clothes-laden washing lines, horse racing tracks, bingo parlors and rundown boarding houses. Wherever you look there are piles of rubble and great swathes of wasteland, the skyline dominated by half-finished, multi-storey buildings, electricity pylons and factory chimneys. The entire city seems devoid of the slightest trace of glamour or sophistication. It’s horrible, its essential nature reflected in the pallid faces, wrinkled brows and booze-loving natures of its unfortunate inhabitants.

Tellingly, Carter does not indulge in any nostalgia upon his return. He only refers to Newcastle once and the word he uses is craphouse.

Winner: Carter.

Lead Performance

First seen striding through Heathrow after getting off Concorde, Harold Shand is a bulldog of a man. Stocky and balding with steely eyes and a broad flat nose, this is a man who struts. And no, he doesn’t strut like Travolta during the opening of Saturday Night Fever. Harold isn’t about self-love. He simply walks that way because he doesn’t have anything to fear. This man owns the space around him and woe betide anyone who enters it uninvited. He’s always alert, always taking everything in and always calculating the odds. It’s a brief but awesome introduction to one of cinema’s most flesh and blood villains.

This was Hoskins’ breakthrough role and he takes full advantage of a dynamite, multi-faceted and very ambitious script (which was also controversial because of its IRA component). One of the great things about the ensuing carnage is that it isn’t Harold’s fault. Things have been harmonious for a decade, probably because he refuses to deal drugs and isn’t into violence for the sake of it. This all paints him in an oddly sympathetic light, even though we know he’s a fearsome scumbag who’s built a kingdom on blood, intimidation and misery. Furthermore, this guy’s funny and likable. He also loves his girlfriend and shows her tenderness.

But as his control is challenged, his ugly side erupts, reaching its bloodiest expression when a subordinate unwisely belittles his significance next to the IRA’s in the great scheme of things.

Hoskins was simply never better.

Throughout Carter, there’s an overwhelming reptilian stillness to Michael Caine’s face. Whatever humor he does display is always sardonic and vaguely threatening. About the only time he cracks a smile is when he sees two brawling women rolling around a pub floor. He might dream of happier times (“When we’re in South America, we’ll make love in the sun” he tells his illicit girlfriend, Anna) but in reality he’s a sour, unforgiving beast whom you just can’t picture relaxing in sunnier climes.

Caine simply excels in this ice-cool role, his Scotch-swilling, shotgun-toting performance in a black overcoat providing the template for many a subsequent gangster flick.

Winner: A tie

Supporting Cast

Friday

Victoria: Initially appearing stuck with something submissive and minor, Helen Mirren grabs this role with both hands and wrings every last drop out of it. Crucially, she never acts like a tough guy, thereby avoiding the mistake that so many of today’s movies make when it comes to portraying strong females.

She plays Harold’s loyal, intelligent and, let’s face it, posh as fuck other half. With her amazing looks and immaculate dress sense, Victoria can light up any room, but Harold is also well aware of her ability to read people, lubricate important meetings and paper over cracks. She’s the perfect hostess one minute, resourceful and influential the next. True, she’s a gangster’s moll, but that seems a dreadfully unfair summing up. For fuck’s sake, this girl can even converse in French.

Anyway, you’d be hard pressed to find a more memorable female presence in a gangster movie. Outstanding.

Colin: Harold’s gay best mate, whose naughty delivery runs in Northern Ireland set everything in motion. Years earlier he saved Harold’s life after an army training exercise went wrong.

Jeff: The only educated man in Harold’s firm, he’s initially cool and composed. However, his obvious lust for Victoria is a good indication he’s not to be trusted. He grows increasingly fidgety and sweaty, getting one of the best lines when he tells the boss’ wife: “I wanna lick every inch of you.”

Razors: First seen cleaning Harold’s Roller, this is a bear of a man with a ferocious scar running down through his left eye and an even more ferocious tash. Loyal and obedient, he won’t think twice about damaging your ever so delicate buttocks. An unforgettable henchman.

Harris: A corrupt councilor, we meet him drinking and handing over confidential info in broad daylight outside a public place. It’s the perfect thumbnail sketch of an overconfident, indiscreet man.

Parky: A bent cop on Harold’s payroll who helps identify the mysterious assailant.

Charlie & Tony: Harold’s American connection comprises the craggy-faced Charlie and the tall Tony. Both are wary and smart, but that doesn’t stop Harold from launching into his memorable dressing down in their hotel room, including his blunt dismissal of Tony as a ‘long paralyzed streak of piss.’

Friday also boasts a large supporting cast and it’s good fun spotting everyone from a Fawlty Towers chef, an Only Fools and Horses regular, at least two members of Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, a British sitcom star, a blink and you’ll miss it Dexter Fletcher as a kid extortionist guarding Harold’s car, a British soap star, and a bloke who turned up in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Carter

Anna: Britt Ekland may have got prominent billing in the promotional material, but she’s hardly in this. In truth, she’s only there to look pretty and whip her bra off, two requirements she meets with aplomb. Just like Friday’s Victoria, she’s a gangster’s moll, but they’re a world apart in terms of impact. Nevertheless, she does get a phone sex scene in her black undies with Carter, deemed racy enough to be cut out of some prints. It’s a case of coitus interruptus, though, as her boyfriend walks in to find her writhing on the bed. “What’s the matter?” he grunts. “You got gut trouble?”

Eric: Friday’s chauffeur didn’t fare too well and neither does Eric here. Perhaps it’s not a good idea to drive crime bosses around if you want a long and prosperous life. Often seen in dark shades, Eric is a slippery shit of a bloke who’d happily sell his mother to the Arabs. Carter loathes him and with good reason. Toward the end we realize he’s gay.

Albert: First seen at the gee-gees with a hotdog hanging from his mouth, his sheer terror of Carter is so great it drops to the ground. Guilty and evasive throughout, he’s a part-time pornographer who arguably gets the best death scene.

Brumby: A successful businessman who made his fortune from amusement arcades, he’s not above wanting to slimily meet Carter’s underage niece/daughter. Permanently angry and flustered, he spends the entire movie almost comically out of his depth. This is a guy who can’t even get his teenage daughter to fall in line so you can imagine how he’s gonna fare with a brute like Carter. Knowledgeable long-term Coronation Street fans will probably be a bit perturbed at his violent demise.

Cyril Kinnear: Crime boss and card shark, the noted playwright John Osborne gives us a portrait of an urbane, seemingly civilized man. He might be polite, but that’s probably because he wields vast power and doesn’t really need to raise his voice. However, he regularly gets disappointed by his subordinates. “See what it’s like these days, Jack?” he tells Carter after a security breach. “You can’t get the material.” But how does anyone become a crime overlord with a name like Cyril? Osborne barely acted in the movies again, which is a bit of a shame.

Doreen: A pivotal figure, she’s also a born victim. Carter fully understands this, knowing the money he hands over at their final meeting won’t make any difference. The moment he tilts her chin up and tells her to ‘be good and not trust boys’ is the only time he expresses any tenderness.

Edna: Carter’s battleaxe of landlady, quite happy to eavesdrop on phone sex. She grasps Carter’s character quickly by quipping: “If you’re a traveler, then I’m bloody Twiggy.” Later clarifies matters even further by repeatedly calling him a bastard. Never appears likely to call the cops, though and is obviously desperate to have her clothes ripped off by him.

Keith: Ah, poor Keith. He speaks well of Carter’s brother and provides good info, but that doesn’t stop our main man throwing him to the wolves.

Glenda: Our main source of T and A, she’s a drunken, double-dealing floozy, willing porno star, and corrupter of youth. I think I’d like to meet her.

Con and Peter the Dutchman: Two gangsters sent by Carter’s London boss to retrieve him before he causes any more trouble. They’re fairly incompetent and Peter isn’t happy when his car gets severely damaged. Both heavily feature in the movie’s classic nude shotgun scene.

Winner: Friday nudges it because of Victoria and Razors.

Quotability

Both movies are chockablock with fantastic lines. In Friday a lot of the good stuff centers on Harold’s increasingly rocky attempts to keep his mega-deal on track with the Americans.

“The Yanks love snobbery. They really feel they’ve arrived in England when the upper classes treat ’em like shit.”

“What I’m looking for is someone who can contribute to what England has given to the world. Culture, sophistication, genius. A little bit more than a hotdog, know what I mean?”

“The Mafia? I’ve shit ’em.”

Friday also excels when Harold vows vengeance.

“This is a diabolical liberty.”

“I’ll have his carcass dripping blood by midnight.”

“I’ll crush them like beetles!”

“Frostbite or verbals?”

Carter’s dialogue is consistently terse and economical. There’s precious little exposition.

“Good God!” Eric exclaims when he first sees Carter. “Is he?” comes the instant response.

(Also to Eric) “I’d almost forgotten what your eyes look like. Still the same. Piss holes in the snow.”

(To Brumby in his own living room) “You’re a big man, but you’re in bad shape. With me, it’s a fulltime job.” Pointing finger in his face. “Now behave yourself.”

(To the badly beaten Keith) “Get yourself a course in karate,” he says, chucking a wad of money onto the bed. Curiously enough, Keith doesn’t seem to appreciate the gesture.

“I’m the villain in the family!”

“Do you wanna be dead, Albert?”

“Goodbye, Eric!”

Winner: Utterly impossible to separate.

Kills & Violence

Poor Colin is stabbed to death at a strangely deserted swimming bath by a rosy-cheeked Pierce Brosnan.

The chauffeur is next, getting blown up by a car bomb.

Erroll the Ponce is slashed across his naked ass with a large knife.

In the most graphic scene, Jeff is repeatedly stabbed in the neck with a broken whiskey bottle.

Appropriately enough for the day which commemorates the Son of God’s death, a security guard is horizontally crucified to the floor and later dies.

Two IRA soldiers and the corrupt councilor Harris find themselves on the wrong end of a shotgun, their dramatic, glass-shattering tumble onto a racetrack probably causing at least one more fatality in a fiery finale.

Plus two abductees in Northern Ireland buy it right at the start.

All in all, I make it eight, maybe nine, deaths.

Carter whacks one of the lookouts at Kinnear’s fancy country house with a log before shoving him into a pond.

Carter smashes a car door window into a heavy’s face, resulting in another goon being dragged along the road.

Peter is shot dead on a ferry.

Glenda meets a watery fate.

Brumby is beaten senseless and thrown off the top of his own unfinished restaurant.

Although unseen, Anna would most definitely have suffered some serious retribution and possibly killed once her affair with Carter became known.

Albert gets repeatedly stabbed in a bookies’ backyard, even though he’s given up all he knows.

Frank’s lying girlfriend Margaret is given a fatal drug overdose and dumped in a pond.

Eric is dispatched with a shotgun butt before wisely keeping his clothes on to take a dip in a very chilly-looking sea.

All in all, six kills, including the very clean handiwork of Kinnear’s hit man.

Winner: Friday

Crap Bits

Friday’s screenplay is watertight. John Mackenzie’s excellent directorial choices are effortlessly smooth. The best I can do when it comes to offering any criticism is Jeff turning up at the abattoir in a flat cap and outrageously fluffy sheepskin coat. Coupled with his pansy-like punching of a helpless, upside down fellow gangster protesting his innocence, his garish fashion sense does actually undermine the scene’s menace.

Jesus, I’m really struggling here, aren’t I?

When it comes to Carter, I remain a little unsure about him getting all teary during his viewing of the crucial porno movie. It seems a tad out of character for such a hardcore nasty piece of work. However, I do love the way he simply lowers his ciggy, his face draining of what little emotion he possesses. For me those reactions would’ve been ample.

Then there’s his sex scene with Glenda, intercut with shots of her hand on the car’s gear knob and the tachometer redlining. Hmm, bit cheesy. Maybe it was fresh in 1971.

Finally, Brumby’s swan dive involves an obvious dummy. A shame as it could’ve been so easily cut. It’s the only moment of violence that fails to convince.

Winner: Carter.

Politically Incorrect Content

Obviously I like this sort of thing to be as high as pos. That’s why you won’t ever find me reviewing the likes of Four Wanky Weddings and a Fucking Funeral. I’ll do Friday first.

Nudity: We get to see one tit of Erroll the Ponce’s blonde squeeze. Not even a jiggling tit, let alone a lovely bouncing pair. One fucking tit in an entire gangster movie. Unbelievable. Even the ever-reliable Helen Mirren, who looks sensational in every scene, frustratingly fails to entertain the boys with a nudey frolic. Plus, for some inexplicable reason, Harold doesn’t own any titty bars or strip clubs. However, we do witness a very young Pierce Brosnan getting his hairy chest rubbed in the shower.

By a man.

In Carter, seventies sex bomb Britt Ekland treats us to a bit of booby action, although she’s easily outdone by Glenda’s romping. Margaret, Frank’s slippery mistress, also gets in on the action, albeit at gunpoint.

Homo bashing: Fair play, Friday is well ahead of the curve. It gives us a positive presentation of Colin, who inadvertently sets the whole train wreck in motion, even if he is only ever seen nicking money or cruising for cock. Harold clearly respects, if not loves his trusted mate, a man who once saved his life. He is genuinely upset by his death. None of Harold’s firm calls Colin a fag or mocks him. This is surprising in the overwhelmingly homophobic world of gangsters, although Harold is not above saying: “You know how bitchy queers get when their looks start fading.” He also mentions Colin’s yen for soldiers, but believes he’d be taking ‘his buggery a bit far’ by traveling all the way to Belfast just to find one.

Nothing to speak of in Carter, although I sense Brumby’s architects are gay in an attempt to create some very loose comic relief. For a start one has a hand on his hip while the other wears a cravat. Both speak in an effete way. No one beats either of them up, although Brumby probably hurts their feelings by being his usual loud, obnoxious and demanding self.

Elsewhere, Peter the Dutchman sports dyed blonde hair and dresses flamboyantly. Despite such blatant provocation, Carter doesn’t offer one gay-baiting taunt, let alone a savage punch in the gut. Mind you, he does shoot him dead.

Violence against women: Very restrained in Friday. Harold slaps a grieving, semi-hysterical widow in front of her kids, but then does the decent thing by ensuring his firm takes care of them all. He also throws Victoria onto a couch, but is mortified and quickly apologizes.

Carter is fifty times less PC here than Friday. Our antagonist is always grabbing and slapping women. They are routinely called bitches, slags and whores. The first sense of a prevailing misogyny is the way Carter rips open Edna’s top without asking, obviously believing that’s how the ladies like it.

There is no equivalent of Helen Mirren’s Victoria here. Women are used and discarded. Nothing illustrates this better than Glenda’s fate. First she’s held under water, dragged out of the bath and unceremoniously marched to the car with her mascara running all over the place. Sure, she’s little more than a quick hump, but she might have also earlier saved Carter’s life. The way he watches expressionless as she meets her ghastly fate in a submerged car boot is genuinely unsettling.

Later, Margaret is abducted at gunpoint, ordered to strip in bush land, and given a lethal dose of heroin.

Racism: Harold might not be a drug dealer, he might not be an out and out thug, he might even respect the ladies, but he’s definitely not an equal opportunities employer. In the most telling scene, he ventures into a Brixton neighborhood looking for Parky’s snitch, Erroll the Ponce. After aggressively finding out where he lives from a young black dude, three other blacks come to his aid. Harold just mutters: “This used to be a nice street, decent families, no scum.”

Erroll, also being black, is, of course, a drug dealer. Not only that, but he’s caught in flagrante with a white blonde woman. Harold is disgusted, his first words being: “Beauty and the beast?” He then tells Erroll to put some deodorant on, the implication being that he smells, not that this provides any protection whatsoever from a subsequent slashing in the kitchen with a large knife.

Later Harold takes a stroll with Parky in the London Docklands as they gab about it being transformed into a major sporting stadium. “Can you imagine nig-nogs doing the long jump along these quays?” Parky asks, although, of course, you do expect that sort of thing from a serving police officer.

Apart from a clear dislike of ‘spades’, Harold is also happy to denigrate the French, Americans, and, most memorably, the ‘pig-eyed Micks.’ Well, you can’t blame him too much for the last one as they are systematically dismantling all his decades of hard graft and trying to murder him.

Only one black dude appears in Carter, a useless guard called Ray. He amusingly announces to Kinnear that Carter is on the grounds only for Carter to immediately walk straight past him into the room. Kinnear shows his usual restraint. “Piss off, Ray,” he finally manages, completely failing to hand out any racial abuse. A clear opportunity missed.

Winner: Friday’s far more racist, but Carter’s got a lot more violence against women and nudity. Carter edges it.

Humor

Harold very much has the gift of the gab. His colorful cockney patter is filled with humor and he’s able to joke about anything from silent deadly farts to his recently car-bombed chauffeur’s hooter and arsehole being nowhere near one another. Harold is also charming and a charismatic public speaker, obviously at ease in different settings. In fact, you might not mind too much if he turned up at a party you threw. He’s an entertainer, all right, and it’s just possible to picture him playing the clown, perhaps making balloon animals or having a go at juggling. Jack Carter, on the hand, would never juggle. He’d most probably bang one of your girlfriends in a broom cupboard before stabbing someone in the garden and taking a leak over your prized koi carp.

Carter’s funniest scene is when Jack is caught by Peter and Con on top of his landlady. They’re a bit lackadaisical though, and instead of taking the extra caution that a rattlesnake like Carter surely merits, they allow their fully naked prey to roll out of bed onto the floor and grab a double-barreled shotgun. As he approaches them wielding the fearsome weapon, Con says: “Come on, Jack. Put it away. You know you won’t use it.” Peter immediately smirks and says: “The gun, he means.” Carter shepherds them down the stairs toward the street as the cracks keep coming. “Mind you don’t catch cold, Jack.” Then they’re all out of the house, the sight causing a gob-smacked neighbor to drop a full pint of milk.

Winner: Friday

The Ending

Friday simply has one of my favorite endings in all of cinema, featuring a bravura piece of acting from Hoskins. Harold, believing he’s sorted everything out, slips into the backseat of his chauffeured car in front of the Savoy Hotel. With a rude jerk, it pulls off, causing him to bark his displeasure. At the same time he realizes it’s been commandeered as the driver’s cruel Irish eyes fix on him in the rearview mirror and Friday’s raucous theme music kicks in. Then that little scamp Pierce Brosnan pops up in the passenger seat smirking and chewing gum while training a silenced pistol on him.

Harold, finally grasping he’s bitten off far more than he can chew, can do nothing but sit there as the Jag rolls through the streets of his beloved London to his doom. The camera never strays far from his face, his emotions obviously running the full gamut from fury to resignation.

Utterly bloody exquisite.

After sorting out the ‘hairy-faced git’ Kinnear, Carter goes after Eric in a lengthy pursuit along the most horrible beach in England. And possibly further afield. It appears to be mainly composed of car parts, oil pipes and mud. Carter pursues an increasingly exhausted Eric, catching him by the huge buckets of a mine’s conveying system. Honestly, it’s hard to believe things like this ever existed and I can imagine environmentalists being more horrified by those buckets ceaselessly dumping waste into the North Sea than by anything else in the movie.

No wonder the goddamn sea is brown.

Carter forces whiskey down Eric’s throat, providing a nice symmetry as that’s exactly what he did to Frank. He kills Eric with a vicious blow from the butt of his trusted shottie before dumping the body in a bucket and watching him get taken out and emptied into the sea.

For the first time Carter seems happy. There’s even some upbeat music to accompany his stroll along the ‘beach’.

However, as he’s about to throw his gun into the water, symbolizing the end of his mission, he’s shot dead by a Kinnear-paid assassin. The tide laps at his prostrate body as sparse music returns. It’s a bleak finale in line with stuff like Easy Rider and Electra Glide in Blue. It works, it’s perfectly satisfying, but very few endings are as good as Friday’s.

Winner: Friday

Conclusion

No, I’m not going to add up the ‘scores’ to announce an overall winner. That’d be childish. Jesus, did you actually think I wanted an answer? Whatever next? Some ham-fisted quest to understand the meaning of Whiter Shade of Pale, Stairway to Heaven and American Pie?

Anyhow, can’t you see if I ever did manage to identify the superior movie, I’d have one less excuse for putting off all that worthwhile stuff you’re supposed to make happen in life. You know, things like composing a symphony, consistently treating people well or at least finally putting my hand up for some voluntary work.

In fact, now that I think about it, The Long Good Friday and Get Carter don’t need the slightest bit of analysis from Nigel, me or anyone else. They are perfect as they are, somehow floating above us all, and will remain that way until the fucking bomb is dropped.

And no, I don’t know whether Hoskins was better than Caine in Mona Lisa.

Dave Franklin once wrote a sensitive portrayal of a latent homosexual in the nuanced, achingly sincere novel, The Muslim Zombies. And he really means that.