After the success of their rightly acclaimed, Oscar-winning 2007 hit No Country for Old Men, the Coen Brothers made two dry, dark comedies in a row, neither of which has garnered the same level of praise as their brooding Texas masterpiece. Though Burn After Reading (2008) has developed a substantial cult following since its release, A Serious Man (2009), though widely praised by critics at the time, is buried and forgotten by most in any appraisal of the Brothers’ work, and may be their most underrated movie. Its comedy is even drier than that of Burn, but they share a sense of absurdity, as well as the bleak nihilism of No Country. Derided by some as an expression of the Coens’ Jewish self-loathing, A Serious Man is really a broader exploration of the uncertainty and apparent meaninglessness of life, and the limitations of both faith and rational science in understanding it.

The idea of a curse from God is established in the very first scene, a stand-alone tale of a Jewish man (Allen Lewis Rickman) and his wife (Yelena Shmulenson) in a 19th-century Eastern European shtetl who may or may not have encountered a dybbuk (Fyvush Finkel), a malicious spirit or demon in Jewish mythology. The wife fears her husband has sealed their doom by inviting the possible dybbuk into their home, but the husband is unworried because he is a self-described “rational man.” His wife does the irrational and stabs the alleged dybbuk in the chest with a screwdriver. The dybbuk (or not) laughs at first, seeming to prove her right, but then he begins to bleed and staggers off into the night.

The wife’s faith in the irrational never wavers, even as her husband is convinced she has doomed them by murdering an innocent man. Whether this story is narratively unconnected from the rest of the movie, or if we are meant to infer that these were the ancestors of our protagonist, Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg), and that this was the beginning of his curse, is left as ambiguous as so much more to come. If a curse did begin in this scene, the question also remains whether it was the husband inviting the dybbuk into the house, or the wife stabbing him, that brought it about.

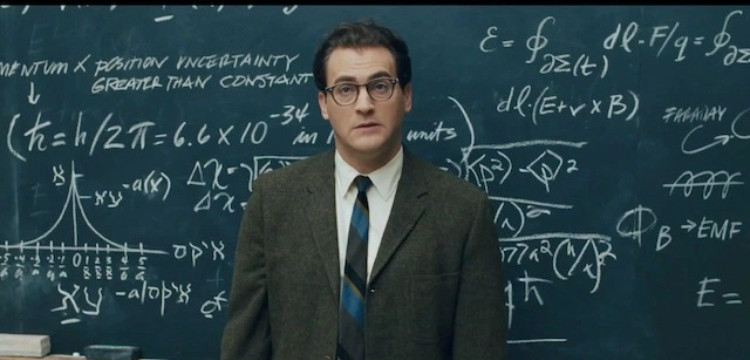

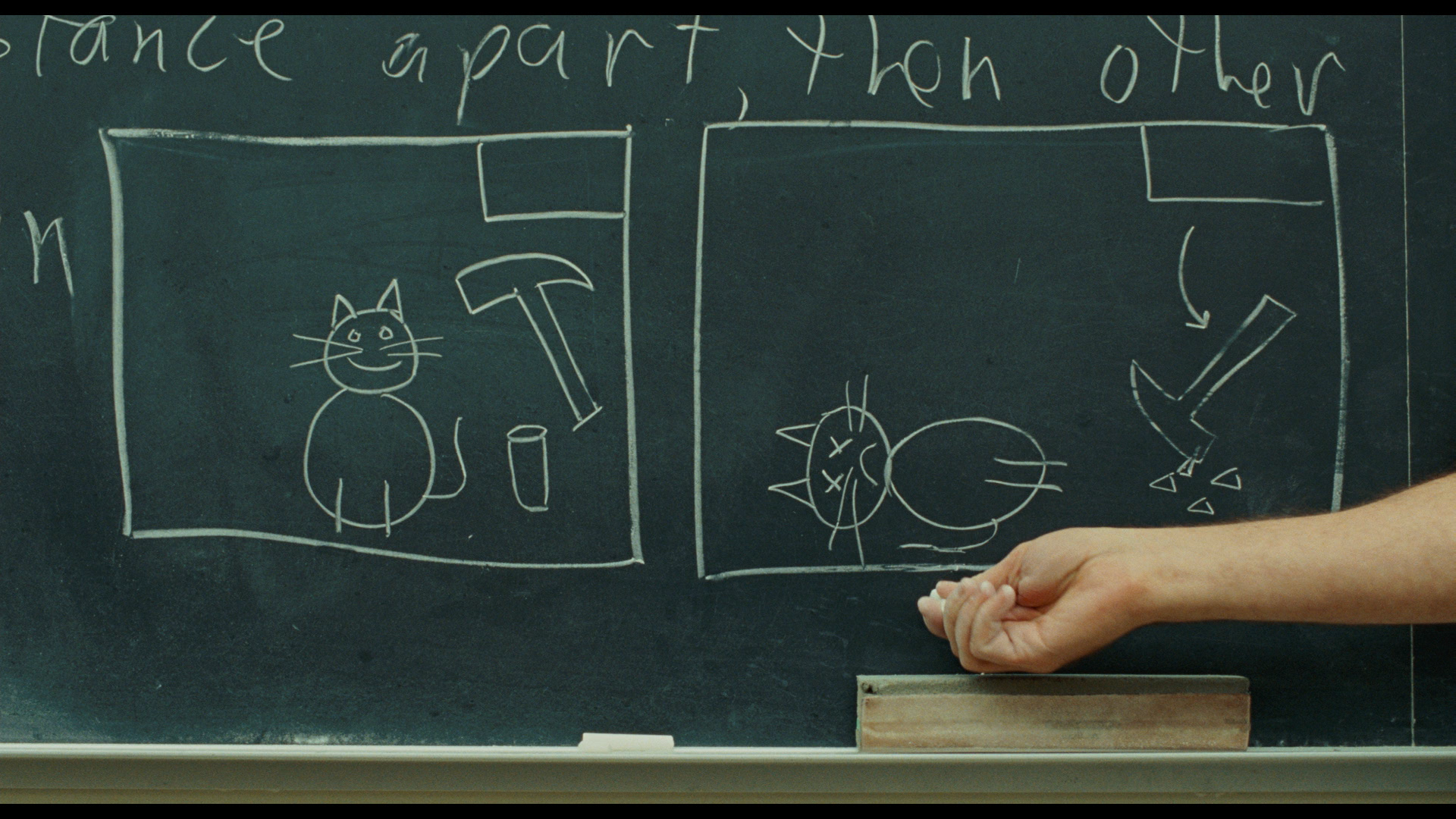

Larry is a professor of physics in 1967 St. Louis Park, Minnesota, and the subject of the first lecture we see him deliver, the Schrodinger’s cat paradox, informs the narrative as much as the biblical story of Job. After class, Larry has a meeting with a student named Clive Park (David Kang), who wants to retake a test and try for a better grade because he “understands the dead cat.” “Even I don’t understand the dead cat,” Larry admits. It is the math that makes sense to him, and this is how he in turn attempts to make sense of the world. Schrodinger and his zombie cat will come up again and again throughout the film, though never so explicitly; this is just the Coens planting the concept firmly alongside that of a divine curse or test (as in the story of Job) in the mind of the viewer. After Clive leaves, “very troubled” by the refusal of his request, Larry finds an envelope on his desk filled with money. The only rational explanation is that Clive left it there as a bribe, but neither we nor Larry ever actually saw this happen, and so his moral dilemmas begin.

The next of his trials begins almost immediately, when he returns home to be blindsided by an announcement from his wife, Judith (Sari Lennick), that she wants a divorce so she can marry Sy Ableman (Fred Melamed). “Sy Ableman???” Larry repeats, baffled that his wife would suddenly want to leave him for their mutual acquaintance, in spite of the fact that Larry hasn’t “done anything” wrong. In their argument we see the same fundamental dynamic between Larry and Judith as in the prologue scene between the husband and wife in the shtetl, and one of Judith’s complaints with Larry is his (rational) refusal to “see the rabbi,” as she says she has begged him to do. Still reeling from this utterly unexpected news, Larry confronts Clive about the bribe the next morning, but Clive denies all knowledge of it, showing he really does understand the dead cat. That evening, Sy Ableman himself comes to Larry’s home to back him into a corner and lecture him on wine before forcing him into a long hug. Job had it easy!

Larry suffers an apparent sunstroke while attempting to fix his TV antenna and spying on his nude neighbor, Mrs. Samsky (Amy Landecker), the sun glaring down at him like a judgmental god. Is he being punished for his sin of lust, or has he just been standing on his roof in the blazing sun for too long? Schrodinger, asked about the existence of an all-powerful deity, shrugs. The next day, Arlen Finkle (Ari Hoptman), the head of Larry’s department, tells him of several anonymous, “denigrating” letters that have been sent to the department, accusing Larry of “moral turpitude.” He repeatedly insists that there is “no cause for concern” and that the letters will have no bearing on Larry’s upcoming tenure hearing, but he does praise them as “eloquent.” It is a very ordinary, banal moment, but Finkle almost seems like a demon sent to needlessly torment Larry, especially when he exits by giving his “best to Judith.”

After a brief property-line dispute with his other neighbor, Mr. Brandt (Peter Breitmayer), a goy (“very much so,” as Larry later tells Mrs. Samsky) who just radiates hostility toward Larry and his Jewishness, our long-suffering protagonist meets with Sy and Judith to talk about the divorce. “I have begged you to see the lawyer,” Judith echoes her previous nag, as she and Sy (with his deceptively soothing, handsy manner) team up on Larry and “ask” him to move out of his home and into the Jolly Roger motel, for the sake of his children. When Larry brings up the very rational point that it would make more sense for Judith to move in with Sy, a widower who has his own house, the two of them look at him like he has proposed a threeway. Sy (a Serious Man, as he is later described with great solemnity) replies, “You are jesting? Really, I think the Jolly Roger is the appropriate course of action.”

As he is moving out, Larry is confronted by Clive’s father (Stephen Park), who insists the whole bribery thing is a misunderstanding due to “culture clash.” “It would be culture clash if it were the custom in your land to bribe people for grades,” Larry says, to which Mr. Park hilariously replies “Yes.” He then accuses Larry of “defamation” for accusing his son of a bribe, while also threatening to get Larry in trouble for taking the bribe, without admitting Clive left it in the first place. Mr. Brandt attempts to rescue Larry with his gallant bigotry, asking if Mr. Park is “bothering” him; apparently, Brandt favors even Jews to foreigners in his neighborhood. “It doesn’t make sense,” Larry says to Park, after politely refusing his neighbor’s implicit offer of a hate crime. “Either he left the money or he didn’t.” “Please,” Park replies, “accept the mystery,” indicating that he understands the dead cat as well as his son.

Larry, of course, is finding it impossible to accept the mysteries of his own faith, which leads him down his subsequent path of the Three Rabbis. The first one, Rabbi Scott (Simon Helberg), is a junior rabbi who offers Larry the wisdom of his advanced years (he looks like he may start shaving in a year or so) and reminds him to see HaShem (God) in everything, even the parking lot outside his office window, “answering” Larry’s existential questions with empty platitudes like “This is life,” and “God’s will.” Audiences may have missed just how funny this movie is amidst all its intentional banality, bleakness, and ambiguity. “Things aren’t so bad,” Rabbi Scott says with camp counselor-esque enthusiasm. “Look at the parking lot, Larry. Just look at that parking lot.”

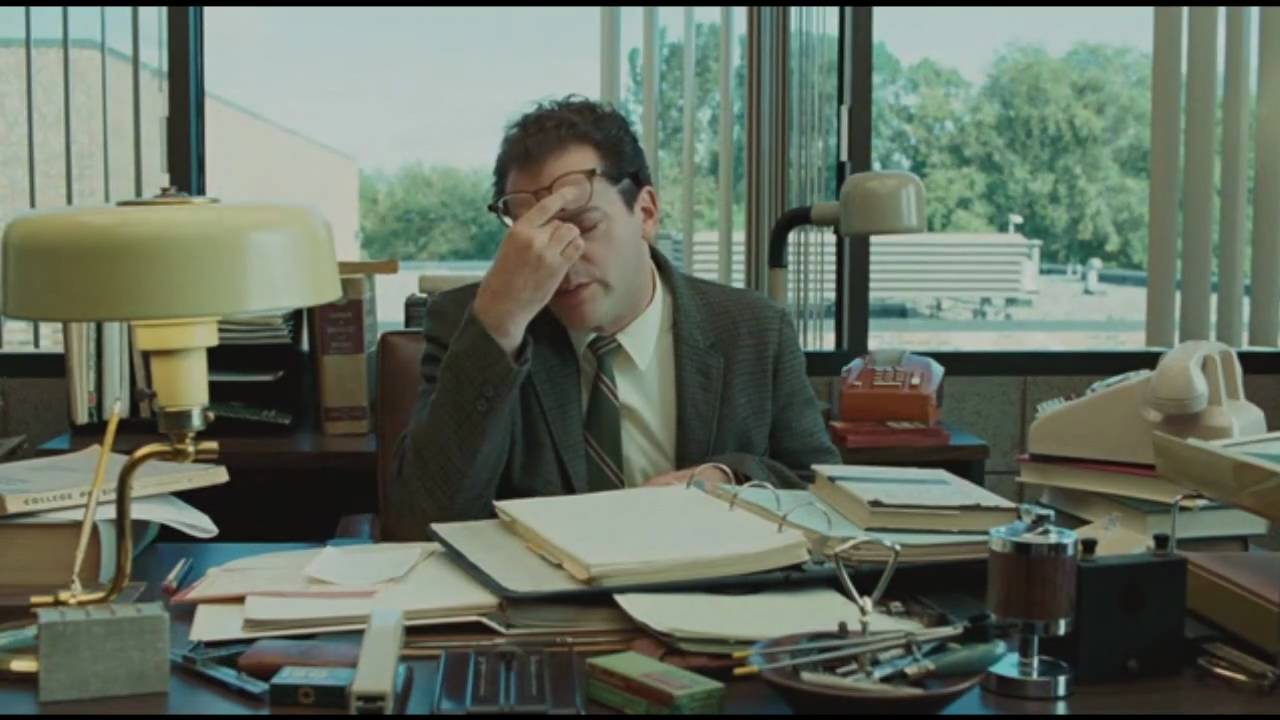

Larry ends up causing a minor pile-up when he may or may not see Clive (the kid is wearing a surgical mask over the lower half of his face) riding a bike alongside his car. He later learns that Sy was killed in another, unrelated car accident, possibly at the same precise moment as Larry’s collision. He wonders desperately what this might mean, existentially speaking, while simultaneously struggling with his mounting financial troubles as the bill for Sy’s funeral lands on him, at Judith’s insistence, of course. Danny has also carelessly incurred a bunch of debt from the Columbia Record Club (remember that?) in Larry’s name, leading to a mild breakdown that sees Larry screaming, “I don’t want Santana Abraxas, I’ve just been in a terrible auto accident!” into his office phone. “I didn’t do anything,” he tells the Columbia solicitor in defeat, repeating what is effectively his mantra.

The Second Rabbi, Nachtner (George Wyner), in response to his questions about what all this chaos and torment in his life means, tells Larry the story of the goy’s teeth: A dentist, Dr. Sussman (Michael Tezla), found Hebrew engravings on the insides of a goy’s teeth, translating to the words “Help me,” of which the patient had no knowledge. Sussman of course became obsessed with finding the meaning of this, and he came to Rabbi Nachtner, who told him, “Helping others¦ couldn’t hurt.” According to Nachtner, Sussman was satisfied with this, and in time he forgot all about the goy’s teeth and moved on with his life. Larry is confounded, demanding a better answer than that, but Nachtner shrugs and says, “We can’t know everything.” “It sounds like you don’t know anything!” Larry shouts. Ultimately, Nachtner gives him nothing more useful than “look at that parking lot,” the sum of his rabbinical wisdom amounting to, basically, don’t worry about it. When Larry asks, “What happened to the goy?” Nachtner looks perplexed and says, “The goy? Who cares?”

Larry briefly escapes the Jolly Roger room he shares with his brother, Arthur (Richard Kind), who had been staying at his house before they were both basically evicted by Judith and Sy, by paying a visit to his sexy neighbor, Mrs. Samsky. They smoke a joint together and Larry momentarily experiences peace as he begins to see the value of Rabbi Scott’s positive perception philosophy through his stoned haze. Soon enough, though, the tranquility has been ruptured by Arthur’s arrest for solicitation and the very biblical-sounding charge of sodomy, and the shame and financial woes this adds to Larry’s burden are once again either a punishment for his transgressions (partaking in the demon weed and presumably hoping to fuck his hot neighbor out of wedlock), or just more chaotic chance. At any rate, Solomon Schlutz (Michael Lerner), the very expensive specialist lawyer Larry retains to help, immediately drops dead from a heart attack after looking over the case, which does little to convince Larry he is not cursed, one would assume.

“I haven’t done anything,” Larry repeats when the department head pays him another visit, this time in reference to any work he might have published or done outside of their university. “Don’t worry,” Arlen reassures him, in the same ironically unsettling manner he displayed in their earlier conversation. “Doing nothing is not bad, ipso facto. Just relax. Try to relax.” The latter sounds almost like a dare. After a few disturbing dreams involving Sy coming back to haunt him with the repeated insistence that he “see the rabbi,” Larry finally attempts to speak with the Third Rabbi, Marshak (Alan Mandell). He stumbles over his assertion to the unimpressed secretary (Claudia Wilkens) that he is a serious man, finally settling on “I’ve tried to be a serious man.” He is ultimately denied all but a glimpse of the reputable and undoubtedly very Serious Man, as the secretary returns to say, “The rabbi is busy¦ thinking.”

Even at his lowest, Larry has the old stereotypical Jewish guilt piled on top of him when Arthur breaks down by the pool outside the Jolly Roger, shouting, “Look at all HaShem has given you! He hasn’t given me shit!” In a dream spawned from this moment, Larry tries to do some sort of right thing with the bribe money by giving it to Arthur to start a new life away from all his gambling debts and sodomy charges, but the plan is foiled by Mr. Brandt and his son, who are out Jew-hunting. This movie is seriously funny in that very special, very dark Coen Brothers way.

Among all his other financial obligations, the Bar Mitzvah of Larry’s son, Danny (Aaron Wolff), has been hanging over his head all this time, and Danny gets very stoned before the ceremony, inadvertently joining his dad in experiencing that parking lot. Mrs. Samsky is even present in the audience, though it is possible he is just fantasizing this; a thirteen-year-old boy with a neighbor who sunbathes nude is unlikely not to have noticed. This is another hint of the “sins of the father” theme running throughout the movie. It is also at the Bar Mitzvah that Judith, in a brief moment of reconciliation, reveals to Larry that Sy greatly respected him, so much so that he even sent letters to the tenure board on his behalf. Anonymous letters, one assumes, and undoubtedly not filled with respect, but Larry is either so numb or so distracted he seems not to react at all.

Danny, whose portable tape recorder (which houses in its case 20 dollars he owes a classmate for weed) has previously been confiscated, causing his own parallel but much more minor trials throughout, actually does get the audience with Rabbi Marshak his father was denied. The wise old venerable is apparently one hip dude, too, because he quotes Jefferson Airplane and gives the kid his proto-iPod back, telling him only to “be a good boy.” Danny now has the opportunity to do the right thing (inasmuch as paying back a drug dealer with money you stole from your sister, who in turn stole it from your shared father, constitutes doing the right thing), and his decision is paralleled with Larry struggling to decide whether to change Clive’s grade so he can keep the bribe money to pay for Arthur’s legal fees. Ultimately, he does, and at that moment he gets a phone call following a seemingly banal medical exam he had at the beginning of the movie. The doctor insists on discussing his X-ray results in person and not over the phone, which is never a good sign, and a tornado simultaneously heads toward Danny and his classmates as their teacher struggles to open the emergency shelter, Danny’s own debt still unpaid.

There is no doubt that the ending of this brilliantly structured, beautifully shot, and superbly acted film has an almost oppressive sense of doom and foreboding. The question remains whether there is truly any meaning to it all, if Larry and his family are cursed by some divine force, or if they (and all of us) are just helpless drifters in chaos and randomness. While Burn After Reading would seem to definitively answer that question in favor of chaos and randomness, A Serious Man steadfastly refuses to open the box and satisfy the hunger for certainty. Somewhere, a cat that is both dead and alive calmly bathes its paws.