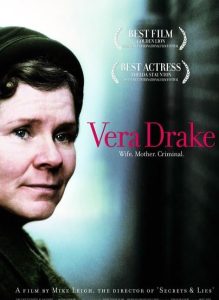

Mike Leigh is arguably the most talented filmmaker alive, and he is certainly the most natural. No one better understands his subjects, and simultaneously holds out more unyielding compassion for the cause of humanity. That said, he is far from a sentimental optimist, believing instead that an artist must present people as they are, which is cause enough to love them. Audiences, especially those who reside within our borders, are rarely moved to embrace anyone who dares express moral ambiguity or a flawed–yet unredeemed–nature, yet Leigh has no such reservations, proving that Europe, at least culturally, reigns supreme over the more philistine North American continent. Perhaps it’s all in the way Leigh prepares his films; extensive rehearsals whereby actors improvise, define their characters, and then contribute to a finished screenplay.

As such, these are lives lived, not the workings of some isolated screenwriter who may or may not understand complex human relations. Above all, this approach allows Leigh to find the essence of his characters, and the dialogue flows exactly as it would, which is even more important given Leigh’s exploration of social class. Compare this philosophy to filmmakers like the Coen Brothers. As talented as they are, they are often guilty of preferring cleverness to realism, which forces us to accept low-class dipshits as sophisticated wordsmiths. Fine, Nicolas Cage is quite funny in Raising Arizona, but there’s not a chance in hell a man of his station would actually talk like that. Leigh, then, is without an overt agenda, which might come as a surprise to many given that his latest release involves abortion.

But it really only involves that politically charged subject, as it is something that the title character performs, but abortion itself is not the reason the film was made. This is not a political statement at all, actually, at least not in the way that we would expect. Leigh avoids the obvious turns (as he always does) and does not resort to grand speeches, courtroom showdowns, or chest-thumping rhetoric of any stripe. He accomplishes this by creating a family (within a larger context, of course) that understands its world quite well, but cannot fathom a development that seems to have no particular place within their ordered existence.

When Vera (Imelda Staunton) is arrested in front of her family at Christmas, everything proceeds so quietly that we have to remind ourselves that we’re watching a family fall apart before our eyes. And how else would it proceed? Imagine the American version: a defiant feminist is hauled away by evil cops, spouting pro-choice slogans like a firebrand, while her family gnashes their teeth, weeps and groans, and vows to set her free. Instead, the Drake family is stunned into silence.

Throughout her ordeal, in fact, Vera is the personification of a woman grasping at the inconceivable. She knows, of course, that she’s been engaging in illegal behavior (this is 1950s England, where the practice was still banned), but she’s as un-conflicted as a woman in her situation could be. Even while being interrogated by a reasonably polite officer (no black moustache here, thankfully), she can only hint at her motivations (she most likely had an abortion of her own as a girl), but nothing is ever spelled out. She believes she is doing the right thing by helping young women in need, but that’s as far as it goes. Again, Vera is no political animal burning for a fight; she’s simply a sweet-natured woman who has the instincts of a caretaker. Performing abortions for poor women, then, would be like putting a young man up for the night, or fixing a hot drink for a cold passerby; it’s simply what one does for another. By taking this perspective, Leigh makes abortion seem more reasonable than ever before. A woman desires it, she can provide it, and it shall be done.

As stated, Leigh would much rather probe social class than anything else, which never quite makes sense to American audiences, who continue to live under the illusion that class barriers are as quaint a notion as, say, unions or the need for a minimum wage. But Leigh knows the divisions exist, both in the past and in our current, seemingly independent, unfettered lives. The abortion issue, then, is but one example of how rich and poor are set apart, as those with connections and cash are never burdened by the law. As statutes are in place not to restrict those who socialize with the lawmakers, but rather to keep the rabble in line, they prove beyond doubt that the entire legal system is merely the accepted manner by which we exercise social control.

While not specifically labeled as such, of course, these laws have never burdened the rich and powerful, and are remarkably flexible when actually tested, even to those who profess to live by the dictates of “strict constructionism.” And while Leigh firmly accepts the idea that the poor are a fucked over lot while the rich do whatever the hell they want, heedless of the consequences (of which there are none), he’s so subtle and serene (unlike Michael Moore or Ken Loach who, despite their talent, would rather shout from rooftops) that it would be easy to miss if you weren’t looking for it. And that’s why I love Mike Leigh without reservation. His films are deep with meaning and consequence, yet could just as easily be mere “portraits.” We’re so busy watching these people live their lives (without meaning ever coming up for them) that the substance becomes a beautiful, unexpected bonus.

Still, an admission is in order. As much as I loved this film, it is fair to say that once Vera is arrested, the film’s strengths ebb a bit. Nothing of this sort is ever fatal in a Mike Leigh production, but the arrest does move the story into more familiar territory, in that there’s only so much that can be done with Vera under lock and key. The most majestic, quietly moving passages are at the outset, where we get brilliantly staged snippets of life for the Drakes. We see them at work (and how many films show characters actually working?), drinking tea, sharing their day at the dinner table, and walking the streets. Even a budding romance between the simple, shy Drake daughter and a well-mannered loser is handled with dignity, which means that, despite the potential for great farce, the film never strays from who we believe the characters to be.

People are always capable of surprising us, but Leigh understands that in many ways, we cling to the familiar, which also means that our limited imaginations rarely carry us into uncharted waters. These young people might appear silly and mere comic relief, but they are completely themselves. Leigh is but a handful of directors in cinema history who has this unique ability to create and present characters in such a way. Compare this to Alexander Payne’s Sideways; a great film, mind you, but one that contains a single painful flaw not necessarily in terms of story, but character. Whenever people act in direct opposition to their natures (at least on film), they cease to be believable and we are left with the machinery of the screenplay, when the first object of a director is to make us forget that we’re in a fictional world.

The entire cast–Philip Davis, Ruth Sheen, Peter Wight, Eddie Marsan, Richard Graham, among others–shines from start to finish, as they prefer authenticity to shallow glamour. There’s not a showy scene to be found, by which I mean that no actor is so ego-driven that they appear to be hunting for praise. As Staunton’s Vera speaks no platitudes, no other character pounds the air with unnatural emotional release, as these are people who wouldn’t have any idea what to do with such melodrama. After all, they survived the Blitz; what can’t they handle?

And when Vera tells her “patients” that they’ll be “right as rain” after undergoing a dangerous procedure fraught with risk, she’s not tossing off some meaningless cliché; she believes it with her heart and soul, as much as the idea that there’s no fix that a spot of tea can’t cure. Vera Drake might not be exactly what Planned Parenthood has in mind (she is practicing medicine without a license after all, and refuses to screech about any cause), but she’ll do. Not as a heroine or even a crusader, but just a woman. A mother, a wife, and a strong, upright citizen of the British empire; a tragic figure of circumstance whose only crime is alleviating pain without judgment, a quality in such short supply as to be invisible. Which is why our final image of Vera is as she begins her prison sentence. And that’s where the Veras of the world will always end up, and they’ll bear it, chin up as usual, because that’s what they do.