Andre Stander was the youngest police captain in the South African Police Service, and in 1977 as the Apartheid government began facing mounting pressure from within, he began robbing banks. His crimes were audacious, and before his initial arrest he would often be the investigating officer returning to the scene mere hours after the heist. Daring beyond the point of recklessness, he captured the imagination of the South African media, and the people began seeing him as a symbol of dissatisfaction with the ruling order that became nothing short of brutal after the Sharpeville massacre. But why did he begin the crime spree in the first place, the son of a police general whose star was on the rise? His partner Allan Heyl noted in a 2002 interview on Carte Blanche “He had no respect for [the police]. He considered them to be corrupt, inefficient, and savage.” Though it is impossible to know the mind of a man, the 2003 film Stander attempts to answer the question of why.

Fortunately, not much is underlined in what becomes a character study. Just as South Africa is coming to grips with an identity crisis more than 400 years in the making, Andre Stander is struggling to understand just what his purpose is as a policeman. He is surrounded by cops who take bribes for a living, and despite being a gifted investigator, is tasked with riot control. At a pivotal scene meant to evoke the opening salvos of the Soweto uprising, the police face down a group of unarmed but very pissed off protesters. Stander attacks two riot police when they blithely voice concern about overtime pay. During the Apartheid era, political disputes were equated with criminal action; hence thieves were in the same cells as African National Congress organizers.

This set up the tidal wave initiated by the ANC of making the nation ‘ungovernable’ with anarchy, and theft and mayhem became political protest. Stander is unable to reconcile his role in this turning point in his nation’s history. Blind rebellion was a subject addressed by the classic My Traitor’s Heart by Rian Malan. Whereas Malan was able to articulate his confusion and dissatisfaction with identifying with a racial group (black or white), Stander is unable to express this in any form other than lashing out. He does this repeatedly, becoming a theme of sorts. He shuts out his wife whilst dancing naked wearing headphones. Time and again he is unable to explain anything to his father or to those closest to him.

And so he begins to rob banks. Initially he does it on a lark, giving away the money, or to take out anger on a teller who gleefully relates jokes about ‘kaffirs’. Stander cannot explain why this is necessary, other than the need to ‘blow off some steam’. Maybe that is all there is to it, except he doesn’t take his rage out on anyone in the bank, or shoot off rounds at bystanders. This is Andre Stander’s impotent counterattack against a society he sees as corrupt and contemptuous, and the media attention he garners with his daring raids reinforces this impulse.

Bank managers are almost excited to have met the man, and citizens voice a bit of joy at the former policeman’s desire to wreak havoc within a world gone wrong. This is no different from the much-misunderstood ‘Mad as hell’ speech from Network. Rather than an eloquent cheer of insurrection, it was a formless and pointless burst of anger at nobody in particular, making no difference whatsoever. This difference is not lost on those close to him, namely his wife, who holds out for the hope that she can find a way to work in a misguided country with an uncertain future.

In a way, people like Stander still served a general purpose as a symbol of dissatisfaction, useful for perspective, but not much use beyond that, even for he and his gang. They have fun with the daring bank heists, the fame and limited fortune, and the catharsis of letting loose with fury at nobody in particular. The film gets this across with panache, and the viewer is swept up in the fun of it all. We are with him when he thumbs his nose at authority while taking down nearly thirty banks while a policeman. That he is eventually arrested is no surprise, but you feel as though something has been lost. And we empathize with the survival instinct that allows him to escape from prison with two men and stay alive on the run as the most wanted men in South Africa.

That the SAPS is busy with nationwide protests and riots only adds to the fun, since the police are unable to focus on the Stander gang since they are busy rounding up and beating confessions out of cheeky bleks. After they rob one bank, they hear on the radio that a larger sum was hidden from them by the manager. And we cheer as they turn the fuck around and go back to get that cash. During one robbery in Braamfontein, his gang walks right past a policeman brandishing a shotgun; but the lack of gunfire and screeching tyres fails to arouse the man’s suspicion.

They rob the bank, walk out past the same officer, and drive away. And they live the high life for a short while, and we look on with envy as they live the way we wished. But the characters must return to earth after an impressive arc. In one revelatory scene, Stander goes to a shebeen (illegal pub) to find the father of a man he killed during a protest; no solid reason given for this beyond guilt, and nothing is accomplished from this apart from feeding the hero’s self-loathing. Or maybe I am wrong about that; it probably benefited Stander well since he knew of no way to deal with his confusion beyond getting the shit kicked out of him.

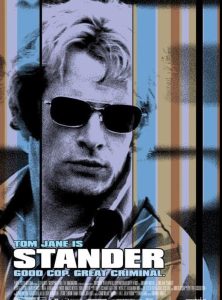

The film is skillfully made, and the director shows both a good eye for detail and fidelity to the facts of the case, choosing carefully to deviate on points that are irrelevant for the sake of drama. Thomas Jane is adequate, and the impossible Afrikaans accent is emulated choppily at best by American and British actors given the director’s aversion to using actual speakers of the language. What is well done is the schizophrenic feel of the country, sharply divided between black and white, with entire sections of the film devoid of any mixture between the two. Some parts seem shot on different continents altogether, and this was entirely intentional.

It is to the film’s credit that it prevents the action from being too much fun, as true freedom for this lot will always beyond grasp. When the gang members part ways, it is clear even to them that money was never the point, and that failure was inevitable. As Stander winds down, and the protagonist attempts one final, desperately clever escape right through Cape Town’s airport, we know that even if he succeeds, he failed long ago. This makes Stander one of the smartest action films in memory, as the catharsis that comes from action is kept at arm’s length where it should be. It retains perspective for those who are truly lost, in a nation that had lost its way.