Let’s unbury the lead before diving into the review itself: During the summer of 1976, in the Central Californian agricultural town of Chowchilla, twenty-six children and their adult bus driver were kidnapped by three armed men, driven around backroads for hours, and eventually buried alive in a subterranean room of dubious construction, supplied with bare mattresses, a small selection of basic foodstuffs, a couple of poorly-functioning fans blowing through cheap conduit, two battery-operated camping flashlights, a pair of boxes with holes in the top to serve as toilets, and a terrifying cocktail of anoxic lethargy and escalating panic.

Childhood trauma may seem like something taken very seriously for a considerable length of time at this point in history, along with “common sense,” which the stubborn mourn as a lamentably bygone skillset, when in fact it’s a fucking myth borne by nostalgia and the death grip of unprocessed generational shame.

However, the human race –at least the serious part– has only recently begun to study, gaze fixed between adult and child once a level place of sacred exchange has been achieved, the inchoate damage wrought upon the young, from horrors survived at infancy to atrocities endured past a child’s first unaided steps, into pre-teen awakenings prematurely eclipsed, and the pulverizing of a thwarted adolescence.

In the aforementioned summer of 1976, twenty-six children, ranging in age from five to fourteen, plus their middle-aged driver, were the senseless victims of an unprecedented, weird-as-shit kidnapping scheme. At the time, these kids were part of a mixed-grade potpourri immersed, sometimes literally, in hot weather academic catch-ups that included outdoor swimming lessons. The sequence to set this up, presented as a blend of archival 8-millimeter film footage and modern dramatic recreation, ably illustrates the emotional faultline for the tectonic traumas to come. These kids, varying from having recently mastered object permanence, to eyeballing each other with nascent butterflies in the stomach, are having a genuine blast behind chain link fences. It’s communal, inclusive, and assumed by parents and teachers to be safe, with the montage humming like the ominous first note of a threnody.

Once the activities of an otherwise uneventful July 15 wrapped, municipal chauffeur Ed Ray drove a bus route made strange and unpredictable by the scattershot demographic of his payload. This led to a path full of sloughs: sloping, muddy depressions often overgrown with thick masses of trees. Such confusing and uneven geography would make later rescue efforts all but impossible, and the kidnappers, we later learn, had come to plan it this way through months of obsessive research… as well as inspiration from a fictional goddamned movie (more on this later).

After a handful of young passengers had been safely delivered to their homes, Ed’s route was cut off by a van from which three men emerged, their faces rendered inhuman by pantyhose, brandishing firearms ranging from pistols to modified shotguns. Orders were shouted and deadly weapons were pointed directly at the kids, some of whom slid under the seats to avoid being shot or from succumbing to mindless animal terror. The train of trauma really gets rolling here, building up steam, momentum and, after several decades, a tragically terminal velocity for a handful of that day’s passengers.

What follows is the most (in)famous part of the story, which some of you may have learned like I did in American history class or, like my parents, via the national nightly news. Dan Rather and Walter Cronkite make contextual cameos, along with various non-English headlines from international newspapers of the time. This was a massive, petrifying event and as far as I’m concerned, it still is, for the searing spotlight it nearly blinded the halls of modern juvenile psychology with.

After roughly sixteen hours of testing load-bearing wooden poles, mesh-covered walls, and finally, a ceiling that split at one point and flooded the crowded space with a torrent of inrushing dirt, a plan of desperation was hatched. Mattresses were stacked into a platform just high enough to reach the peak of the space, and a duo consisting of Ed the driver and fourteen-year-old Michael Marshall embarked on an hours-long battle with a “manhole cover” hatch weighed down by untold pounds of dirt, as well as sensory hallucinations triggered by primal fear and disorientation.

This last, among other details, is explored in a throughline of modern-day interview portions within the film. A selection of law enforcement personnel, investigators, survivors’ family members, attorneys, journalists, and the formidably compassionate child & adolescent psychiatry specialist, Doctor Lenore C. Terr, talk about the points where they each entered the fray of this extended nightmare.

I suppose this is a spoiler, but either I’ve already spoiled it by trying to wrangle this story into a prose-paddock, or you know the outcome because, no exaggeration, the “Chowchilla Children” are one of the primary reasons that counselors and trauma-response teams now materialize in the wake of America’s seemingly endless succession of mass shootings and domestic terrorism attacks. The kids and their driver eventually escaped the room, which turned out to be a janky rolling storage trailer buried like the casket of a brontosaurus a few hundred yards from an active quarry.

“Ed Ray Day” was announced in the town after a West Coast-spanning investigation was launched, and this generally unassuming man was heralded, branded, and some might say damned as a hero. Never comfortable with the praise, and polite to a fault, Ed failed to publicly acknowledge the far superior efforts –which nearly cost him an arm during one particular escape attempt– of the young Mr. Marshall.

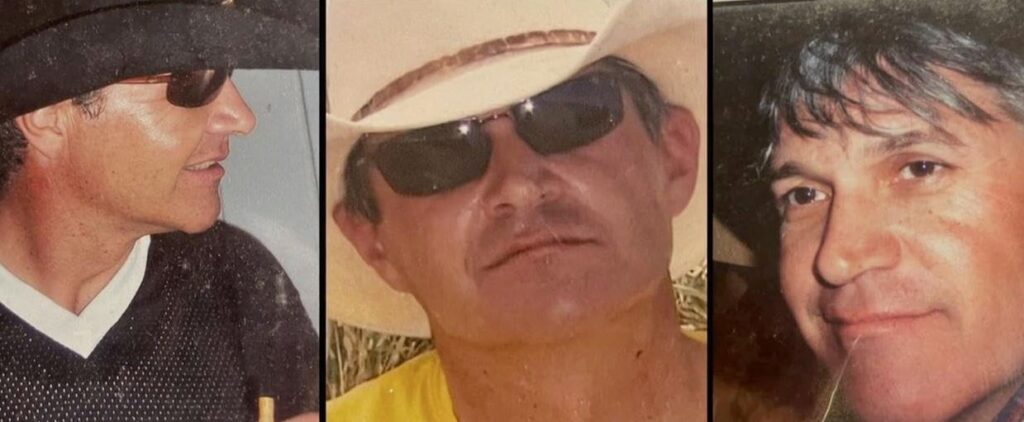

Michael’s ensuing trauma, shared with his fellow students, was ironically compounded by the dangerous exertions he made that would lead to sunlight and gusts of fresh air finally entering the buried trailer. And in a turn of fate I saw coming like the gaseous headlamp of a freight train at midnight, adult Michael succumbed to alcohol and substance use disorder as his dreams of being a bona fide cowboy and rodeo star, lasso and spurs at the ready, collapsed under the weight of nonrecognition and survivor’s guilt.

Other children, including Jennifer Brown Hyde and Larry Park, were so stamped by the experience that spirals of depression, legal entanglements, and battles of faith had left them emotionally scarred to a degree that their families found incomprehensible. Jennifer’s brother (also a passenger and captive) died five years after the kidnapping, in a farming accident, which led to compounded stigma by her community and an eventual exodus from the Chowchilla area altogether.

Another tragic figure forged in the furnace of the ordeal was Jodi Heffington, who had rallied many of the children to focus on escape during the bleakest moments of the ordeal and who went on to attend, decades later as an adult, nearly every parole hearing the three perpetrators were given, eventually passing away (far too soon) at age 55 due to complications from chronic alcohol abuse.

Oh yeah, let’s talk about the trio responsible for this unconscionable horror show. The ringleader, Fred Woods IV, heir to a mineral mining dynasty, wanted to be free of his father’s monetary control and became obsessed with –this is where reviewing this film for Ruthless Reviews comes into queasy, too-sharp focus– the first Dirty Harry film. Remember the third act, where Scorpio hijacks a school bus full of children and drives it into a quarry?

So, Fred Woods and his double-digit-IQ cronies, siblings Richard and James Schoenfeld, designed this elaborate, completely unoriginal, potentially mass-murdering, patricide-inspired trauma-cannon and fired it in the dead of summer, 1976. Because the victims were not as stupid as their victimizers, the trio awoke from a post-felony nap to see the children and their driver being interviewed on local news less than a day later, realized the plan had gone smash, and ran like hell. The film chronicles the dizzying drives, flights, and mad dashes to places as far as western Canada, as well as three eventual captures and prosecutions. I will leave further details out because I need to get back to why I decided to review this one.

Childhood trauma. Until roughly four decades ago, America did not take the idea of a juvenile brain being rocked hard enough to calcify into scar tissue seriously, leading to countless addiction-disordered individuals, corrosive marriages, imploded families, and attempted or successful suicides. Along with thousands of case studies, the tragic yet ultimately redemptive story of the Chowchilla Children gives hope to our paradoxically beautiful-hideous species, in the form of effective language, working models for healing, and legal precedents that protect future victims of conscience-bereft motherfuckers.

I recommend the film. I recommend long walks. I recommend plenty of fluids. And most of all, I recommend reading many of my talented comrades on this site. Yes we traffic in unpulled punches, but most of us think that stealing a school bus full of children is evil, and it’s a far better use of our time to rant about how well- or poorly-endowed our deceased presidents are, or listing the ABC’s of literally every subject we can think of .

Oh, and if there is a moral to the Chowchilla story, from the perspective of the kids, it’s to genuinely never give up. Their situation was petrifying, suffocating, and without any sign of hope… and all twenty-seven human beings eventually climbed out of a hole in the earth. That is its own special kind of Ruthless.

Leave a Reply