Abstract expressionism has always been about the abdication of responsibility. Disguised as a new way of seeing, or interpretive systems not bound by tradition or permanence, this revolution of the post-World War II art world has, by design, rendered the very idea of meaning null and void. If the worth — emotional or intellectual value — of a work is entirely up to the individual and cannot be evaluated using any firm set of criteria, or at least rules and boundaries that do not shift from one work to the next, then each and every reaction is acceptable, which is the admission of anarchy into what has, for centuries, been a strikingly controlled craft.

The trick (or “game,” if we’re being honest), of course, is that despite the belief that a painting is whatever the viewer brings to it, there remains the ability to fail the test and misinterpret what is supposed to be free of such archaic restrictions. If one doesn’t “get,” for example, a Jackson Pollock, that response is seen not as a valuable assessment in its own right (could a painting’s meaning be that it has no meaning?), but rather a failure of understanding altogether. And yet, the possibility that a Pollock could be bullshit, or the mad ravings of a drunk psychotic, does not enter into the equation because, for all of its liberating tendencies, abstract art is as rule-based and conservative as the schools of thought it allegedly rebelled against. As such, there are in fact keepers of the kingdom, and through sheer snobbery and alarming protectionism, they alone decree how a work is to be assessed in the public sphere. Hatred or even mere dislike is assigned the label of ignorance, and sheer confusion a laughable “condition” that has but a single cure: conformity and subservience to the prevailing winds.

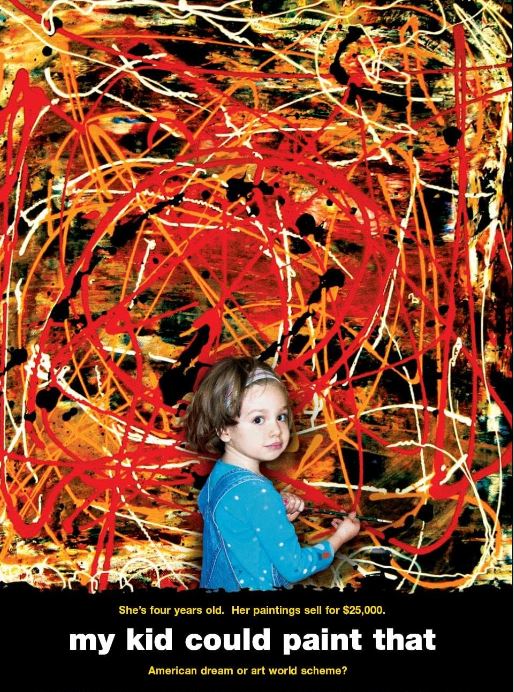

Amir Bar-Lev’s tough-minded My Kid Could Paint That attempts to document the inherent contradiction of abstract art — that it ends up becoming what it claims to hate — only to evolve into much more, or less, depending on your perspective. The stuffed shirts who see the world through their own dirty navel deserve a sound beating, of course, but had it been nothing more than a smarmy attack on pretension, its worth would have ended at the closing credits. Instead, this is a full-scale war on numerous fronts, a fierce, entertaining summary of fraud, living vicariously through our children, failed ambition, and the bold consideration that art, at least in the West, continues for no other reason than to allow people to feel connected to something deemed important by the free market.

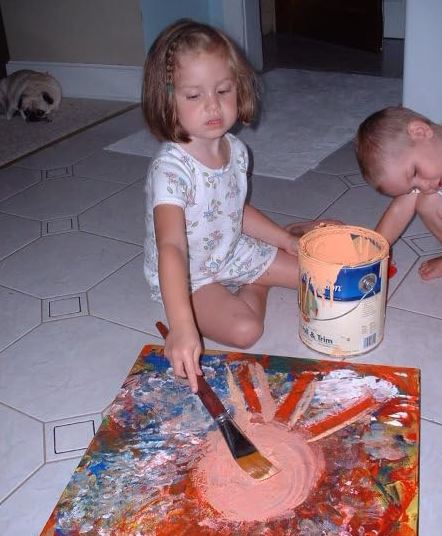

The key figure in all this is Marla Olmstead, a four-year-old girl who is, by all appearances, a child prodigy; a young Pollock whose work defies comprehension. Bar-Lev started this project with the full intent of exploring an all-too-interesting question: if this child is capable of producing what so-called experts claim is “abstract art,” then what does that term even mean? As four-year-olds lack the brain power to know what the hell they are doing, is it the belief, then, that unconscious, even primitive brains can produce masterpieces of the form? Or does art require intent? Clearly, intent and context prevent the whole of life being deemed “artistic,” but here we have a child acting upon a canvas, so is that enough? Are her formless visions actually quite deliberate and calculated? Or is the randomness itself the expression?

As Marla’s paintings make their way around Binghamton, New York, she generates a buzz that would not come if she were thirty-five, but that’s just being cynical, right? It’s obvious that the girl’s work is valuable precisely because it seems to be implausible, and that the interest stems from a desire to get in on the ground floor of what could be a cultural phenomenon. But that’s art in the modern age: the entire conversation revolves around deals and price tags, and whatever these pieces might “mean” is lost to the winds of time. Records continue to be broken at Sotheby’s and the like, and Marla — clearly unique, given her youth — is just what a static art world needs to secure relevance once again. Her greatest champion is her father, Mark, a curious fellow who is, by turns, shady and unexpectedly charming.

It should surprise no one that he once dreamed of artistic success, and that fact alone is the necessary motive for fraudulently attributing his own work to Marla. Some thirty something nitwit with a few tubes of paint? A dime a dozen, and if you’ll kindly get out of my office. But a child genius? A Mozart of the canvas? That, my friend, means headlines, big crowds, and phones ringing off the hook. As expected, art is about an angle, and young Marla becomes the meal ticket for more than just the parents who are able to sock away some much-needed college tuition money.

The turning point in the Marla adventure is a 60 Minutes program that seems to point out that whenever the child is filmed doing her work, it never quite resembles the paintings that have so enchanted the art world. To answer that charge, a hidden camera was placed in the ceiling to ensure that Marla wasn’t intimidated or pressured in any way. There again, the final product was shabby and, well, childish; exactly what one would expect from a girl at play. In a flash, Marla’s paintings stopped selling, and it looked as if she would be a footnote on the pages of history; a flash in the pan as fake as Hitler’s diaries. Mark never does admit fraud, of course, but in the course of filming, it does seem that at the very least, he “coaches” the child, which in itself compromises the integrity of the work. But is it more than that?

Based on side-by-side comparisons, it appears to me that Marla may have started the paintings, but another hand was responsible for shaping them into a final product. That said, even Mark’s work must be considered insipid, and it’s not really the point that he used his daughter to act as a front for his dreams. Yes, it’s rotten and abusive to manipulate your kid into performing like a trained seal, but the work, regardless of the author, is still defended with the utmost sincerity. One scene in particular, where a breathless buffoon describes what he sees in what amounts to Marla’s spilled diaper with the added menstrual blood of dear old mom, is enough to hang the abstract world all by itself, though defenders of the faith would likely dismiss the clown as an aberration. Still, to listen to the man’s wonder and excitement regarding doors, pathways, and spiritual depth with images of Marla’s mindless squeezing of paint tubes still dancing in my head, is about as close to high comedy as I’ll witness all year. His lunacy should sound the death knell of what amounts to a well-financed cult, but as long as there are millionaires throwing money at crap, we’ll have numerous Marlas to contend with, to say nothing of assorted lesbians and trans-gendered Africans shitting on stage for justice, liberation, or the latest fad passing as a movement. That they all spring from the same impulse is beyond debate.

Even the filmmaker comes to the conclusion that he’s been duped (reinforced by a candid scene where Marla lets slip the fact that her brother, all of two, actually painted something for which she received credit), though Marla regains her footing after the parents produce a full-length, start-to-finish DVD that “proves” their child is a true artist. That her finished work looks nothing like the paintings produced off camera doesn’t seem to faze the sycophants and buyers who crawl back to the gallery, and her legend is re-born with even more force. Even after the questions and mini-scandal, her paintings fetch as much as $25,000 each, which is obscene on at least a hundred different levels, but actually makes sense in this particular world. The final dollar value of art is simply rich people talking amongst themselves, and the sky is the limit whenever deep pockets are tied heavily to the quite rational need to possess what others want. Some even talk of Marla’s paintings one day being priceless, and this is more than a remote possibility. Aesthetic value? Adherence to form?

Such considerations long ago left the building. This is best typified by a Hummer-driving couple who stalk around an art gallery trying to decide which Marla masterpiece they simply must own. Not surprisingly, not a single word is said about the work itself; it’s all joining the parade of glitz, glamour, and utter fascination. These people have been told the girl is gifted, the painting is good, and that it should hang in their living room. The purchase has all the dignity of a desperate used car salesman peddling a rusty Pinto, and it depresses to no end that there’s an innocent child in the midst of all this. The lengths to which we will go to feel as if we’ve made our mark on this burning rock makes for some fine filmmaking, but it doesn’t help me sleep any better at night.

Marla may in fact survive her abuse, and dad may himself succumb to alcoholic despair for lying with impunity, but these two minor figures aside, we now have yet another arrow in the quiver with which to blast holes in the husk of one the 20th century’s most enduring frauds. Rather than looking at the world anew, or an evolution in thought, abstract art has been crafted from day one to employ and enrich assorted carnies, con-men, and grifters who would otherwise wander along, homeless and bereft. The impact on the collective experience has been devastating to be sure, as the rot has further infested universities and once respectable institutions of higher thought and civility. It’s about feeling superior, nothing more, and as such, it’s a closed society with all the secret handshakes, obscure jargon, and exclusionary tactics that would send envy coursing through the veins of Skull & Bones.

And to this day, I have never once received a satisfactory explanation as to why a work of abstract expressionism is brilliant (or even what it means), instead being subjected to assorted lashings that conveniently mask the emptiness of their case. Look upon Marla, then, not as a diversion, or even a temporary setback, but the culmination of decade after decade of flawed logic. Eventually, a perverted worldview will crack under its own weight, and it makes all the sense in the world that the last, dying gasp would spring from the mouths of babes. It’s been regressing for so long, it might as well be about the children again. Abstract art infantilized the world, reducing a once proud civilization to a disjointed cacophony of lies, half-truths, and vicious schemes. The body is rotting from the inside, and Marla’s here to remind us of the stench.

Leave a Reply