Back in the day critics complained Arthur Penn’s directorial masterpiece glamorized crime, desensitized folks to violence, made them more aggressive, was a terrible influence on the young, and played fast and loose with the truth.

Well, excuse me, but I’ve never understood such limp assertions.

For a start, only anal viewers make a big fuss about details, as if such deviances from reality are pivotal to a story’s success. Documentaries and factual books should strive for accuracy not movies. Instead, films ought to be plausible and entertaining, a creative process that involves bending facts, simplifying stuff, making shit up and employing all kinds of other tricks to bamboozle the layman. I mean, was the real-life Bonnie Parker as chic and goddamn sexy as Faye Dunaway? Doubt it very much, but I can’t fathom how anyone thinks that would damage a movie.

More importantly, how many people watched Bonnie and Clyde and then went out and robbed a bank or shot at some hairy-arsed cops? Films don’t have the power to seduce (let alone compel) you into doing anything seriously anti-social, no matter what the shit-stirring media, religious bigmouths and moral busybodies like to say. Fucked-up people will always do fucked-up things, but they don’t do them because they’ve just visited the cinema or rented a videotape. There’s a world of difference in enjoying actors pretending to do aggressive shit on the big screen and being up close to or involved with real-life violence. Christ, people don’t embark on shooting rampages because they think they look cool emulating the likes of Clint Eastwood. They do it because they’re resentful, inadequate, self-loathing wretches that wanna make others pay for their mistakes, bad luck and horrible experiences.

And apart from anything else, people were doing horrible things to each other long before the age of cinema. We are killer apes, my friend. Violence dwells within us. It always has and it always will. Do you really think Genghis Khan, Jack the Ripper and Klaus Barbie were getting amped up watching torture porn before committing their atrocities?

About the only discernible effect Bonnie had was a knock-on effect in making movies fonder of splashing the red stuff around. And why did movies immediately do that? Because Bonnie was a massive hit. It was what cinemagoers wanted to see. As for the luminous Dunaway, I suspect the influence of her gun-toting antics didn’t extend much past a handful of young ladies in the audience popping out to buy a natty beret.

She appeared in two flicks before Bonnie, but it was this 1930s-set bloodbath that made her a star. Its early scenes depict her all by herself, sultry and bored. She’s an astonishingly beautiful, 21-year-old Texan waitress with one of the best pairs of… cheekbones you’ll ever see. When she glances out the window to see the dapper Clyde Barrow (Warren Beatty) trying to steal her mama’s car she suddenly has a reason to get off her bed. Now she can put her honed femininity to use because there doesn’t appear to be anything else to do.

However, when he mentions he’s just got out of jail for armed robbery she freezes. This is the right response and we expect her to scuttle back inside. Instead she listens to him lobbing in some details about having chopped off a couple of toes to evade prison work and we begin to suspect that Bonnie is a cliché: a good girl in thrall of bad boys.

“What’s it like?” she says.

“Whaddya mean?” he replies. “Prison?”

“No. Armed robbery.”

Uh-oh.

A minute later he’s covertly showing her his gun on the street and she’s running her fingers along its barrel, no different from Henry Hill’s eventual wife in Goodfellas in that she’s turned on by the prospect of unpredictability and danger. Once Clyde holds up a store she’s hooked and is all over him in the getaway car. Herein lies a big problem, though: Clyde’s impotent, a condition that is an affront to a gal like Bonnie. His inability to do the bizzo simply doesn’t make sense, a direct undermining of her womanly charms. Or as she snipes: “Your advertising’s just dandy. Folks’d never guess you don’t have a thing to sell.”

Bonnie might always be playing with her hair and looking in the mirror (the opening image is an enormous close-up of her lips) but she’s no Silly Girly. Once taught to shoot she’s quite happy to get her hands dirty, even if that means poking a Tommy gun through a window and blazing away at a bunch of cops. By the end she’s a battle-hardened soldier.

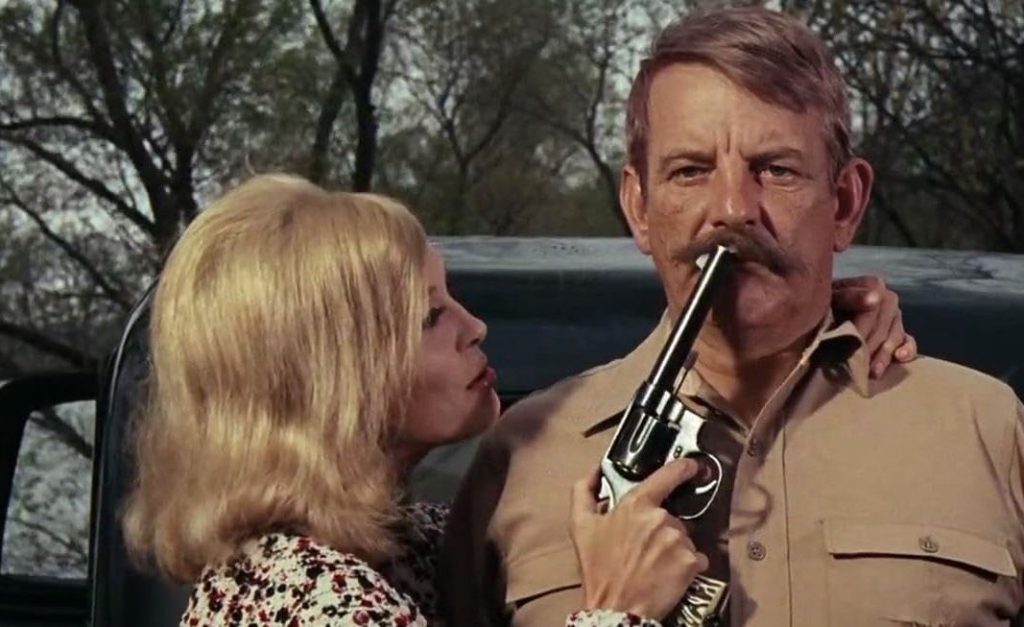

The Oscar-nominated Dunaway is excellent throughout, a vibrant, deliberately modern showpiece in her drab, Depression-era surroundings. Her expressive face ensures her emotions are always transparent, whether it’s the sadness generated by visiting her old mother (who seems to know the end isn’t far away for both of them) or the kick she derives from posing alongside a captured lawman for a gloating photo. Indeed, this might be her best scene as she smooths the humiliated man’s mustache with the tip of her gun.

Nevertheless, Bonnie is no romantic portrait of illicit lovers on the run. For all the spills and thrills she is mostly an unfulfilled woman that tires of her rootless existence (“When we started out, I thought we were really going somewhere. But this is it. We’re just… going.”) Our antiheroes are corruptors, criminal parasites and murderers that lust after notoriety, their twisted love built on a useless existence and the self-centered excitement of lawbreaking.Bonnie deservedly launched Dunaway on an absorbing career that went from strength to strength until the 1980s arrived and those divine cheekbones were rudely bruised by the debacle of Mommie Dearest, a smack in the face from which she never quite recovered.

Leave a Reply