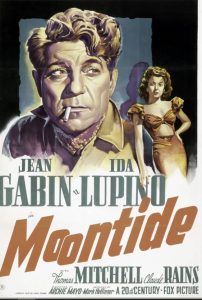

Jean Gabin made a career out of playing damaged characters with good intentions, making him a natural for noir. His roles in Le Quai de Brume and Le Bete Humaine were those of good men with a violent past, and despite their industry and good intentions, they were unable to escape that past. In Touchez pas au Grisbi, he was a gangster going for that one last score, which meets with a tragic ending. In one of his few English-speaking roles, Gabin steps into the familiar dirty shoes of the drifter with a tragic side in Moontide. Though there are better film noirs from the 1940s, and the direction is fairly dry and leaves a lot to be desired, Moontide is a fine character study that is not to be missed. And, lets’ face it, this is Jean Gabin we are talking about. One of the finest actors ever, possessing a combination of grace and fierceness with a dash of raw sexuality, Gabin could make a bowel movement compelling and heart-rending.

In Moontide, Gabin brings the sort of presence that can fill a screen quite easily, and he seems here physically unable to play an unlikeable character. He is Bobo, an affable drunk and wandering dockworker whose good-natured ways always seem to land him a job wherever he drifts. Apart from having a good time, his philosophy is to continue moving, preferably in unpredictable ways. As he explains to a girl who has become attached to him: ÂI am not a peasant I am a gypsy, and the gypsy is not dead just yet. His winning performance appears to be a rather shallow sketch at first, until a reason surfaces for this ethic. He falls in love with a girl shortly after she attempts suicide, and gives her a place to stay, insisting that she really doesn’t want to know what led to her desire to drown in the ocean. This is not as much chivalry as reciprocity  he would rather hope his past could remain similarly in the shadows.

There is no need to rehash the plot, which involves a murder and a double-cross, since it is incidental to the film; it is driven by characters rather than plot. The best films always are, since plot-driven films give one the idea that the destination was predetermined, whereas character-driven ones just drift along with the tide. Every moment of the journey has potential, which makes the end considerably more difficult to see. Midway through the film, one peripheral character obtains a damning bit of evidence related to the aforementioned murder. He regards it in front of a fire, smiles to himself, and adds it to the flames. I bring this up as such an important plot point is generally used to forward that plot, rather than provide commentary on the main character  the moment adds nothing, and everything, to the story.

Being a noir, decisions made in Moontide only lead further down increasingly dark corridors. Despite his survival instincts, Bobo decides to abandon the way of the gypsy, and take a chance at love and enter the wholly unfamiliar territory of home. There is even a femme fatale, though it manifests as his fat, manipulative partner, Tiny. Though he at first appears to be a helpful agent who wants to see Bobo achieve his full potential, he sweats homoerotic overtones with his increasing desperation to control his friend. Though Gabin looks like he could kill a man with a feather duster, Tiny becomes a threatening presence nonetheless (to Thomas Mitchells’ credit  he is the Philip Seymour Hoffman of Hollywood’s Golden Age).

Gabin would return to France after the war was over, and would remain a central presence in French cinema until his death in 1976. Hollywood probably did not know quite what to do with him, since he hardly fit the mold of a pretty-boy leading man. His career includes some of the greatest films ever made, including Grand Illusion, and his resume burst with complex characters. Gabin was one of those rare performers who could simultaneously exhibit power and vulnerability; solid as a mountain, yet all too easily broken by powers beyond his control. Moontide may be one of his lesser works, but still a rich one by any standard.