The underappreciated gem: The Mosquito Coast (1986)

“How did America get this way?” Allie Fox (Harrison Ford) asks while driving around his hometown. “This place is a toilet.” The thing is, the pictures that unfold at the start of The Mosquito Coast don’t match his words. Everything looks like run of the mill.

So why the discrepancy?

Simple. Allie Fox is one helluva deluded man.

Or as Charlie (River Phoenix) says of his half-mad inventor father: “He grew up with the belief that the world belonged to him and everything he said was true.” Have you ever heard such a concise recipe for bitter disappointment and imminent self-destruction?

It’s easy to see why Schrader was attracted to turning Paul Theroux’s excellent source novel into a screenplay. Allie is a restless, driven survivalist and almost impossible to deal with. He’s opinionated, rude, sarcastic, condescending, overbearing, paranoid and ultimately dangerous. A patriarchal bully. People grow visibly distressed whenever he strides into their lives.

In other words, perfect Schrader material.

Mosquito Coast was one of the few Ford movies that didn’t do well at the box office. I’m not sure why, but having the word ‘mosquito’ in the title probably didn’t help. Ford also got accused of being miscast. I don’t think so. He’s a terrific actor, but playing a cunt isn’t really his bag (as shown in the groan-worthy What Lies Beneath). However, the difference here is Allie Fox doesn’t know he’s a cunt. In fact, he sees himself as a towering hero, although he prefers to modestly call himself ‘the last man.’

One thing’s for sure, though. He wants to leave America, a consumer society where people have lost their way and do nothing but ‘buy junk, sell junk, eat junk’. His grand vision involves relocating his wife and four young children to the jungle where he can start again. When told the country he’s chosen is ‘back in the Stone Age’ he quips: “Sounds perfect!” Like the real-life Reverend Jim Jones, he has a God-like disposition. He angrily rejects non-believers and ends up trying to build a utopia. Whenever challenged about his beliefs or course of action he insists: “I’m our salvation.” There’s a wonderful contradiction bubbling away within Allie in that he’s a fierce atheist who wants to be declared a god.

Indeed, his clashes with the missionary Reverend Spellgood (a particularly good Andre Gregory) make for excellent cinema. Allie insists the bible ‘doesn’t work’ and hates Christianity’s passive nature of enduring burden when he’s all hands-on solutions for the poor natives he’s landed among. Spellgood wants to get people under his thumb through religion whereas Allie wants to do the same with reason, critical thinking and the wonders of science. They’re different sides of the same coin. Both are infused with that dangerous affliction known as certainty. When Spellgood tells Allie the Lord sent him to the jungle, Allie spits out a contemptuous retort: “The Lord hasn’t any idea this place exists! If he did, he would’ve done something for these people a long time ago, but he didn’t. I did.”

Allie is a pure example of the ‘Right Man’. This concept, first outlined by the science fiction writer A.E. Van Vogt, attempts to explain idealistic men who can never accept they’re wrong. They’re likely to fly into a rage if reality clashes with their world view. Historical examples include tyrants like Hitler and film stars such as Peter Sellers. This is why Allie likes to rant in front of children. They don’t have the intellectual ability or experience to argue against his hardcore opinions. In one perfect scene he starts ranting at a native kid over the roar of a chainsaw. The guy just can’t shut up. (Theroux’s novel memorably ends with his tongue being torn out by a vulture). Allie keeps imagining Armageddon is just around the corner for the States; indeed, he welcomes such devastation so he can be proved right in his faraway hut (“No shame to be the last to go. Just proves my point.”)

Still, there’s no doubt he’s a dynamic maverick and a genius with all things mechanical. This is a man able to construct an ice-making machine in the middle of a humid hellhole (‘ice is civilization’). However, there’s also the lingering suspicion he can be as dumb as a bag of hammers. For example, Allie thinks he can demonstrate his God-like powers by showing a faraway tribe a block of ice, even though this involves carrying it over inhospitable terrain for a day or so. He also builds a ‘new civilization’ but doesn’t consider it might need defending from outside forces. His behavior makes me recall Annie Hall’s Alvy Singer musing about intellectuals: “They prove you can be absolutely brilliant and have no idea what’s going on.”

The Mosquito Coast is tremendous cinema, although there are a couple of nitpicks. Allie’s grounded wife Margot (Helen Mirren) is presented as much more sympathetic, yet thinks nothing of dropping everything to cart her admirably un-annoying children off to a harsh new world. I’m also not sure how Allie manages to get his hands on barrels of ammonia and arc welding equipment in the middle of the jungle. Still, The Mosquito Coast remains a compelling portrait of a man ‘going upriver’ who loves America too much to watch her die.

Some duds: Obsession (1976), The Comfort of Strangers (1990) & Bringing Out the Dead (1999)

It’s easy to forgive Schrader for De Palma’s early hit Obsession in that the finished film was nothing like his script. Obsession is a well-directed piece of deeply implausible pap with a fine Bernard Hermann score. Only Schrader completists should bother. Having said that, maybe it’s worth a twenty-minute peek just to check out Cliff Robertson’s half-dead, staring performance and ever-changing skin tone. I kept expecting him to slump to the floor and stop moving altogether.

Obsession is slow, but Comfort is like wading through odorless glue. Hardly a surprise as it was written by Harold Pinter. Now this guy is a million times more successful than yours truly, but I’ve never cared for the psychological meanderings of his screenplays, such as The Servant, The Go-Between and French Lieutenant’s Woman. The maxim action is character is one he appeared to ignore all his career, resulting in yet another dud in the form of Comfort. It’s about a pair of pretty thickies who can’t read the room, even when violently assaulted. Here we learn there’s no other word for ‘thighs’ while the only thing that happens during its first hour is Natasha Richardson puking into a Venetian canal. Otherwise, we have to listen to Christopher Walken periodically attempt an Italian accent while inexplicably wittering on about his father’s tash. Hey, there’s slow burn and there’s ash. Venice is far and away the most intriguing aspect of the whole shebang, which only made me wish there were a murderous red dwarf running around.

Schrader’s first three collaborations with Scorsese resulted in fireworks but ended with the damp squib Bringing Out the Dead. This box-office turkey remains one of Scorcese’s least loved films and it’s easy to see why. Schrader might have managed to come up with an appealing title but he forgot to add a story. It’s a weird mix of OTT stuff, hallucinations and drama. The performances aren’t convincing. There’s no point to most of the characters. The attempts at humor fall flat. The music is weak. Scorsese’s visual tricks do nothing to disguise the script’s paucity. And paramedics sure as fuck don’t behave like that.

Nic Cage plays a strung-out ambulance driver who’s getting some strange ideas about death, spirits, guilt and all the rest. Fair enough, and there’s plenty of scope for interesting developments, but Dead fails to embrace its supernatural underpinnings. Why is Cage haunted by the patients he’s lost? It’s not like he knows them. And anyway, surely paramedics deal with death every working night, especially in a fucked-up place like New York City? What on Earth is this repetitive, episodic flick trying to say? Cage tries to explain in a weary voiceover, having come to believe his job is not about saving lives but bearing witness. “I was a grief-mop,” he says. “It was enough that I simply showed up.”

And that’s all Dead does. It shows up.

Religion: The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Dominion (2005) & First Reform (2017)

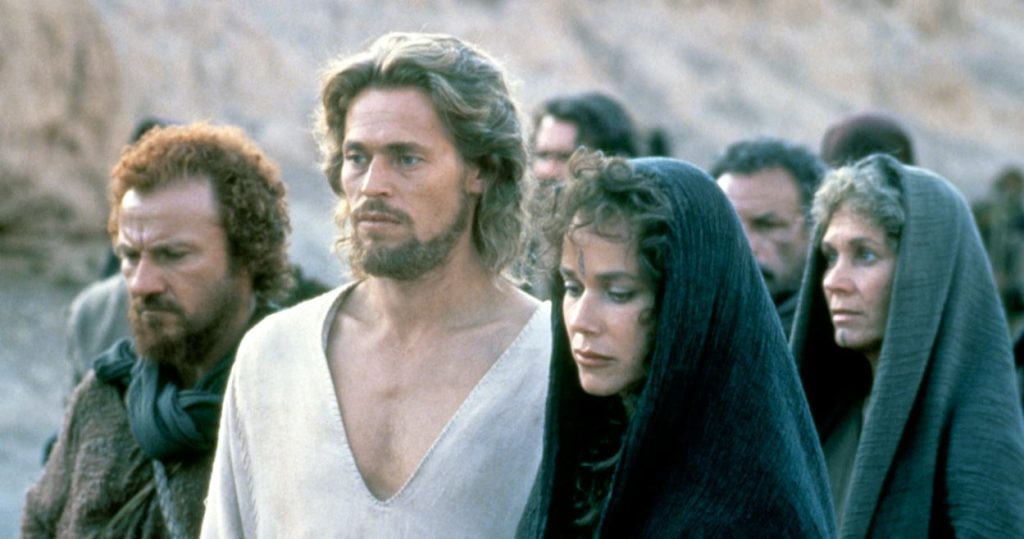

The last Jesus movie I watched was Passion of the Christ, which failed as both entertainment and Christian propaganda. Scorsese’s effort is a bit better simply because it has some creative divergences from the thuddingly familiar story. The problem with both is the subject matter. I mean, there’s something so profound yet inherently ridiculous about portraying the Son of God doing his thing that the center can never hold. Of course, being an atheist does make it tricky to give such material a fair go. I quite liked Temptation’s deviations though, such as the newly resurrected Lazarus getting murdered. Hey, you live, you die, you come back to life and then someone sticks a knife in your guts. Guess them’s the breaks, although it’s a shame we don’t get to see God explaining to the poor sod why all that seesawing palaver was necessary. Are you starting to grasp the fundamental problem I have with such a religious epic? Perhaps it’s just a question of how much Schrader’s po-faced screenplay makes me snigger.

Quite a lot, actually.

Still, I doubt he could have come up with anything that would have enabled me to embrace a near-three-hour depiction of holy high jinks. I guess a Trainspotting-like approach might have helped. Alas, Temptation is devoid of whip, humor or anyone shitting the bed, leaving me a trifle disappointed that not one character from Galilee to Jerusalem manages to whisper: “He’s not the Messiah. He’s a very naughty boy.”

At the beginning of Temptation, a written disclaimer makes it clear events are fictional rather than based on the Gospels. Funny, I thought the Gospels were fictional. Anyhow, Scorsese’s cute little proviso didn’t save him from being engulfed in controversy and death threats back in 1988, apparently unaware that God-botherers have a tendency to hate freedom of expression, especially if it involves anything other than reverence.

However, Temptation does feel a lot more bonkers than Passion. For a start it not only shows our main ‘man’ as less than perfect by helping the Romans crucify their opponents, but dares to show him humping. Then there’s the plain odd stuff like him sitting with a load of other johns in some first century porno theatre watching Mary Magdalene being screwed. Or pulling his heart out of his chest, which must rank as the gimmickiest moment Schrader ever penned. As for the other biblical stars, Judas is a militant scenery-chewer while John the Baptist is an angry dude whose baptisms resemble open air raves, complete with naked ladies in a trance. Not long afterward Jesus wanders into the desert, sits in a circle for ten days, and proceeds to chat with whoever turns up. “Look at my breasts,” a cobra voiced by a hooker tells him before making way for a talking lion.

Honestly, these religious types are fucking nuts.

Schrader’s dialogue is impossibly silly all the way through. “I feel pity for everything,” Jesus says. “Donkeys, grass, sparrows…” Later he tells Judas: “I am a heart and I love. That’s all I can do.” Sorry, not even the Saviour of mankind can get away with such clunkers. The only person who doesn’t sound like a tool is Bowie, who gives an effective cameo as a rational Pontius Pilate. When Jesus outlines his universal creed of love rather than killing, Pilate calmly shoots the ‘Jewish politician’ down in flames. “It’s against Rome,” he insists. “It’s against the way the world is. Killing or loving, it’s all the same. It simply doesn’t matter how you want to change things. We don’t want them changed.”

Jesus (Dafoe) comes across as a tormented, doubt-filled, scared hippy magician with Commie underpinnings. Who occasionally pities donkeys. Not once does this whiny wannabe world-saver grasp his contradictions. He’s happy to cure blindness and turn water into wine, but when challenged by some doubting townsfolk to do something magical he says: “The Messiah doesn’t need miracles. He is the miracle.” After discovering a temple filled with money lenders, he yells at one: “You’re filled with hate! Get away! God won’t help you!” Er, isn’t Jesus and his heavenly dad s’posed to be into forgiving and saving?

Too many scenes don’t ring true whether it’s a blaspheming Jesus avoiding beatings from those he’s upset or Mary Magdalene being rescued from imminent mob violence by Jesus spouting a few trite words. Episodes have the sort of resolution that can only happen in the movies. Plus, it’s one helluva talky, strangely redundant movie. At the end of the day it’s just another overlong retelling of Jesus’ time on Earth, albeit with some eye-catching bits that were always going to ruffle orthodox feathers.

Still, Schrader does manage to capture the religious mindset. And by that, I mean people at their stupidest. Listen to this exchange among Jesus’ disciples: “How do we know the Baptist really said that?” “Everybody said he did.” “But how do we know?” “Well, even if he didn’t, the words are important.” “Why?” “Because people believe them.” So, there you go. Truth, evidence and facts don’t matter in the slightest; it’s all about what you believe.

Temptation might have marvelous production values and a good score, but it’s still a load of hokey, overwrought shite. And I didn’t even mention Harvey Keitel’s God-offending gingery perm.

Schrader had another go at religion with 2006’s derided Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist. A reasonable Nazi-flavored opening manages to turn into a thoughtful first half, but it’s downhill after that. Our dog-collared hero ends up fighting bad CGI and a bald, floating, nappy-clad baddie who’s a piss-poor Linda Blair substitute. It’s silly, scare-free stuff that doesn’t have much to say about the nature of good and evil. Given Hardcore also disappointed, I wouldn’t have much of an argument if anyone insisted Schrader’s religiosity has never directly translated into a decent movie.

Then, late in the day, he came up with the superb First Reformed. In many ways it’s a typical Schrader flick: a voiceover, diary keeping, chilly restraint, and an isolated man on the brink. Yet where such an approach bored in flicks like Light Sleeper it packs a wallop here.

Pastor Ernst Toller (an excellent Ethan Hawke) is not having a good time. His son was killed in Iraq, his marriage has fallen apart, he’s drinking too much, he can’t relate to anyone, and cancer has just come into the picture. He’s in charge of an out-of-the-way tourist church that has a congregation of less than ten, a situation that only increases his propensity to drink and dwell on unhealthy thoughts.

Then he’s asked to counsel a deeply troubled radical environmentalist, who can’t handle the prospect of fatherhood. His wife Mary (Amanda Seyfried) tells Ernst: “He thinks it’s wrong to bring a child into this world. He wants to kill our baby.” The husband believes the apocalypse is around the corner. He simply asks: “Can God forgive us for what we’ve done to this world?”

There’s no action whatsoever in First Reformed and Schrader mostly keeps his camera static, but it’s never less than compelling. It artlessly wades into a plethora of weighty subjects such as guilt, suicide, existentialism, mortality, climate change, extremism, and the Church and big business getting into bed together to fuck over our planet. Characters are convincing flesh and blood creations, especially the joyless loner Ernst. He’s no foaming at the mouth, head in the clouds, religious idiot. His feet are on the ground and he knows full well Godliness and prosperity are not connected. The man is intelligent, compassionate, articulate, insightful, and good with kids yet ends up contemplating the most terrible slaughter. He understands desolation, arguing that the blackness in our hearts is nothing new. “Courage is the solution to despair,” he says. “Reason provides no answers. Wisdom is holding two contradictory truths in our mind simultaneously: hope and despair. A life without despair is a life without hope. Holding these two ideas in our head is life itself.”

Some people struggle with First Reformed’s ending, but it’s the old Taxi Driver trick of a character indulging a wild flash of fancy. Schrader’s thorny screenplay, a glorious testament to the mans ongoing relevance, was rewarded with his first Oscar nod.