The biographies: Raging Bull (1980), Mishima (1985), Patty Hearst (1988) & Auto Focus (2002)

Raging Bull is an essential watch, but it’s the kind of unsentimental, uncomfortable two hours that’s easier to admire than love. Jake LaMotta (De Niro) is an archetypal angry, destructive and self-destructive Schraderian character, although he stops short of being suicidal. From what I can gather Schrader was brought in to rewrite someone else’s screenplay before his efforts were rewritten and built upon, leaving his contribution to Raging Bull a wee bit murky. As such, I’ll return to this modern classic at a later date to look at it from another angle.

The well-regarded Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters has to be my least favorite Schrader. Mishima, like Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ, is definitely one of Schrader’s men with a death wish, but this is a relentlessly talky, stagy and dull two hours. It’s also pretentious and avant-garde, adjectives I don’t normally associate with Schrader. Worse, it doesn’t make me wanna seek out anything from the acclaimed Japanese writer’s extensive body of work.

Schrader’s next biopic tackled Patty Hearst, an unusual move in that he put a woman front and center. By that I mean his oeuvre demonstrates he finds the extreme behavior of men much more appealing. Fair enough. So do I. Unfortunately, Schrader was jumping on the bandwagon as Patty’s barely believable 1974 ordeal (in which the abducted teenage heiress graduated to robbing banks with her misfit captors) had already been filmed at least four times by the time he got round to it. Patty Hearst doesn’t bring anything new to the table.

Schrader repeats his Hardcore mistake in failing to flesh out Patty’s (Natasha Richardson) family ties. I don’t think we get one pre-kidnap shot of her with her mum and dad or friends, undermining its emotional impact. Instead, she has to tell us: “I grew up in a sheltered environment, supremely confident. I knew, or thought I knew, who I was…. There is little one can do to prepare for the unknown.”

Too true, baby.

Then she’s bundled into a car boot by the Symbionese Liberation Army, an inept bunch of pseudo-military, Commie blowhards. “The people have declared war on the fascist American government,” they politely inform her after chucking her blindfolded ass into a closet. “The revolution is happening right now, bitch.”

Boy, this is one confused handful of bourgeois-hating, urban guerrillas. They want to be poor but rob banks; they’re apparently working for the people but are happy to point guns at their heads. Oh, and sex is a ‘revolutionary act’. All of them are rhetoric-spouting caricatures, permanently frothing at the mouth about ‘hungry babies’ and ‘corporate enemies’. Like any fanatics, they don’t know a joke between them and are fucking boring to listen to, but at least their ladies do half-naked push-ups. After five minutes in their shrill, over-earnest company you can’t help being on the side of the ‘pigs’. Schrader presents these Che Guevara wannabees as resentful clowns, but sadly stops short of outright satire (although I did enjoy Patty’s confession to her abductors: “I’m really struggling to overcome my bourgeois upbringing.”)

Patty Hearst is watchable, non-essential Schrader, even if it’s rather choppy and lacking in any killer scenes. I don’t think Schrader sinks his claws into the titular character anywhere near as deeply as someone like Bickle. Perhaps that’s because it’s more difficult to conjure up an explanation for the madness of real-life events. Patty, who gets the benefit of my doubt when it comes to her criminal commitment to the SLA, probably sums it up best: “I’m not sure what happened to me.”

It’s much easier to tell where Auto Focus‘ Bob Crane (Greg Kinnear) goes wrong. The poor sod can’t keep his dick in his pants. It’s like a penile Godzilla rampaging through his life that, on the surface, is sedate and conservative. Now I don’t believe in sex addiction. Those who claim to have it are cowards trying to excuse poor, consciously chosen behavior by presenting themselves as helpless victims. It’s a classic case of refusing to accept responsibility for your actions, a belief system that can excuse the likes of alcoholism, kleptomania and paedophilia. However, Bob (the erstwhile star of classic TV sitcom Hogan’s Heroes) sure does his best to convince such an all-consuming condition exists.

Schrader previously aired his fascination with porn and sordid sex in Taxi Driver and Hardcore. The former featured Bickle thinking a first date at a porno cinema was a good idea while the latter gave us a devastated George C. Scott enduring an eye-opening film of his missing teenage daughter getting jiggy with two guys. Schrader plunged back into smut with Auto Focus, the seedy story of a man on the up who opens Pandora’s Box and can’t help trying to fill it with jizz.

The flick starts on a pitch perfect note with a big band swing number accompanying the title credits in which we’re reassured ‘a little hanky-panky gives the boot to Mr. Cranky’. Bob is doing fine as a radio DJ but is itching for a big TV break. The script for Hogan’s Heroes lands on his desk around the same time he meets the liberated, less than ethical home video expert, John Carpenter (Schrader favourite Willem Dafoe). It’s a heady mix and suddenly our slightly dull, ardent Christian hero is playing drums in strip clubs, attending swinging parties, having orgies and secretly videoing naked conquests. Hey, haven’t we all done that?

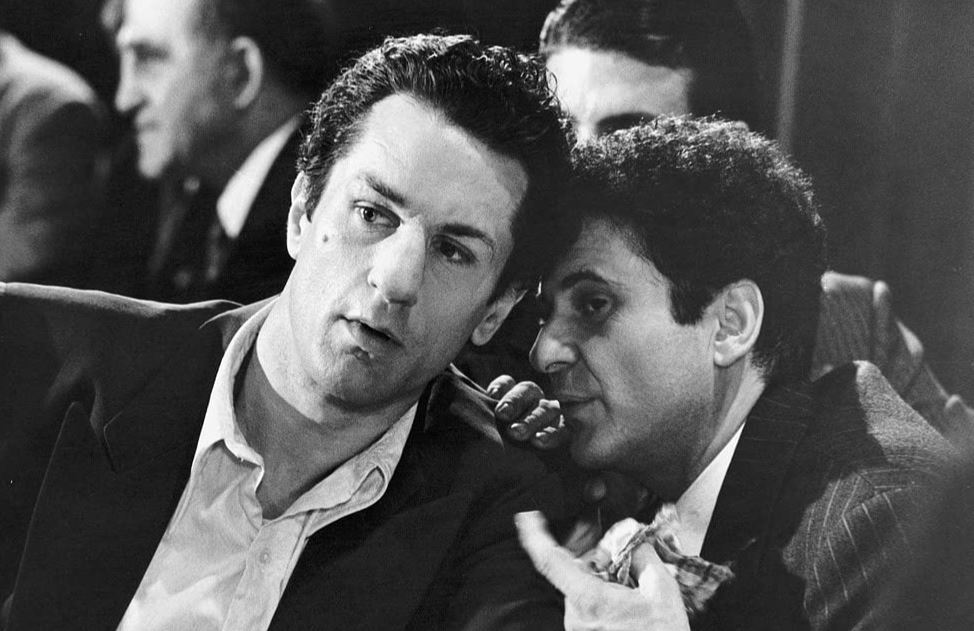

Bob’s slide into sex addiction, sorry, willfully fucking and photographing every piece of skirt that comes near his permanently engorged cock, is well done. It’s understated, dispassionate and believable, the result of character flaw, chance, and the intoxication of fame set against the backdrop of mushrooming sexual freedom and the darker side of technology. The clean-cut Kinnear is excellent as the hypocritical churchgoer, a faithful husband who’s initially so naive about his newfound opportunities that when a floozy tells him she’ll do anything he wants, he simply asks to keep the lights on. The needy, equally pathetic Defoe (complete with darkened irises) pretty much plays Satan, continually whispering temptation into Bob’s ear. Auto Focus is a smoothly directed, intelligent watch with some sly undercurrents of humour. It’s among Schrader’s best.

Crime: The Yakuza (1974), Light Sleeper (1992) & Affliction (1997)

Schrader’s intellectualism is hard to miss. I’d say this talky approach (along with a perverse insistence on perfunctory or plain dull titles) is the main barrier to his flicks reaching a wider audience. Most start with a voiceover, a telltale sign that action’s gonna take a backseat. Schrader’s never been the go-to guy for wild car chases and rip-roaring explosions, you know? Even in his best movie Taxi Driver there are only two action scenes: Bickle shooting an armed robber in a corner store and the climactic slaughter. Schrader has long shown he has no interest in penning the equivalent of Commando.

His repeated forays into the crime and neo-noir crime genres (which you might expect to have a fair bit of action) illustrate this reluctance to portray sweaty, out of breath characters or white-knuckle sequences. His first screenplay to see the light of day was The Yakuza, a pic he co-wrote with his brother (which was then extensively rewritten). Despite dealing with Jap gangsters, there’s not a whiff of violence in the opening thirty-five minutes. Indeed, it prefers to concentrate on the good guys and the oriental obsessions with honor, obligation, duty and face to the point I’d argue it’s a misnamed pic. The yakuza are left to potter around in the background rather than tear the screen up. They’re presented as honorable with a definite code instead of coke-snorting, bloodthirsty savages preying on the average Joe. A shame, as we instead have to watch them sitting around in oversized nappies smoking, bowing, gambling and barely raising their voices. The Yakuza is a respectful portrait of modern-day Japan. Too respectful, really, as the flick takes an age to shift into third gear. If you want to boil The Yakuza down to its essence, it’s the story of a man getting to the point where he can rationalize the voluntary amputation of a finger. I’d love to tell you that makes it finger-choppin’ good, but the combination of its anemic villains and an over the hill star turn from Robert Mitchum mean it’s solid rather than spectacular. Yes, there’s a closing bloodbath that proves to be a Taxi Driver/Rolling Thunder forerunner, but it’s too little, too late.

Taxi Driver gets echoed again in Light Sleeper in that our main drug-dealing character is a diary-keeping insomniac who ends up with a gun in his hand. There’s little to recommend it, though. Just like 1990’s The Comfort of Strangers, there’s no action whatsoever in its opening hour. Even a key suicide is not depicted. Instead, we have to make do with the backdrop of an irrelevant garbage strike, a dwarf cop trying to act tough, and the soundtrack’s grating, half-arsed songs. Reputedly Schrader’s most personal film, I’d put it (along with 2021’s The Card Counter) among the former coke addict’s most boring.

Affliction also has barely any action and waits seventy-five minutes until introducing a minor car chase. Nevertheless, it’s an engaging, memorable watch. Perhaps that’s because of the perfectly cast Nick Nolte and the Oscar-winning James Coburn, who both deliver sterling performances. Then again, Schrader’s script is intelligent and convincing, resulting in him helming a low key but quietly unsettling pic.

Wade Whitehouse (Nolte) is a cop in a sleepy, snowbound town. He’s doing his best but his marriage has died, his little daughter would rather be anywhere than in his company, and the locals don’t seem to treat his authority with much respect. Worse, his new girlfriend senses he’s damaged goods. She tries to reassure him: “Your father’s not like you. That’s why you and he are strangers.”

The father in question is Glen (Coburn), a hard-drinking, mean sonuvabitch with very traditional ideas about women and children. At his wife’s funeral, we hear a terrifying summation of her recent existence: “You never know how much women like that suffer. It’s like they live their whole lives with the sound turned off.”

Somehow Wade’s clean cut, teetotal younger brother has managed to escape Glen’s shadow, but there are already signs Wade is doomed to follow in his dad’s footsteps. “You know I get the feeling like a whipped dog some days,” he says. “Some night I’m gonna bite back, I swear it.”

Affliction simply explores how far the acorn falls from the tree.