The Heaven’s Gate moment: Bonfire of the Vanities (1990)

Do you ever avoid a flick because the critics pissed on it? You know, stuff like Ishtar and Battlefield Earth. The laughable quality of these efforts is so taken for granted that they’re only supposed to be trundled out if a snigger fest is required. I know I’ve made no attempt to watch. I mean, all those people can’t be wrong, can they?

And yet, when it comes to the peculiarities of art, the intrinsic quality of a movie can never be proven. If ten million people think it’s shit but you love it, then your opinion is as worthwhile as anyone else’s. In fact, your opinion is king. Sure, you can’t prove you’re right, but those millions of naysayers can’t prove you’re wrong, either. Heavyweight awards, box office returns, critical consensus and what your mum and best mate think really do mean jack shit.

End of story.

So fuck what others say. And fuck what I say. Try to approach a flick with an open mind and judge the goddamned thing on its merits alone.

Does this mean I’m now gonna defend the mega-flop Bonfire to the hilt? Well, no, and I would argue that Tom Wolfe’s darker, more acerbic source novel is a much better way to spend your time. Still, I can’t see why the movie was such a critical punch bag back in the day. Every scornful review I glanced at seemed to imply that if you bumped into De Palma it was fine to blow raspberries at him and let down the tyres on his car.

Now Bonfire is rather limp, but it’s a passable two hours, even if Tom Hanks and Melanie Griffith are a long way from my faves, the bespectacled Bruce Willis is miscast, and Morgan Freeman delivers an On Dangerous Ground-like sermon at its conclusion. There are much worse flicks in De Palma’s fifty-year-long career, such as the incoherent bollocks of Raising Cain and the yawn-inducing bollocks of Femme Fatale. The main interest Bonfire generates is trying to work out why De Palma was thought suitable to take on such arch material. After all, it’s a race-flavoured satire focusing on the trials and tribulations of a privileged, lightweight WASP. No murder, no gangsters, no icky sex stuff and no steamy showers. It’s just not lurid enough for a bloke like De Palma, you know? Maybe he should’ve given Hanks telekinetic powers or a thousand-dollar-a-day coke habit. We do get some trademark directorial moves, such as an opening five-minute tracking shot and a split screen, but De Palma had already shown he couldn’t do knockabout comedy in the mirth-free misfire Wise Guys. Why he was handed the reins for a more sophisticated kind of humour is a bit of a mystery. I was, however, amused by Bonfire’s palpable fear of blacks as well as Griffith’s breast size tripling since the days of Body Double.

Conclusion? I’ll probably get around to watching Ishtar one day.

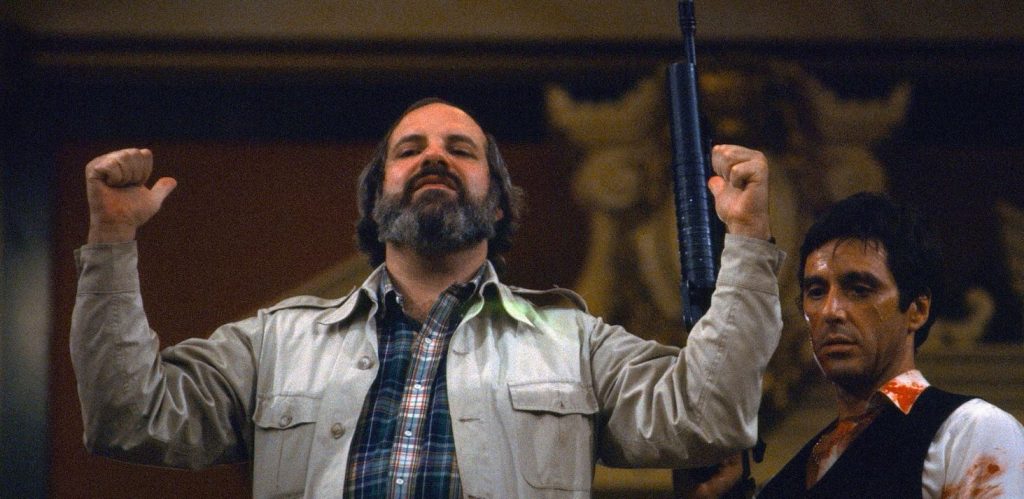

The glorious Pacino connection: Scarface (1983) & Carlito’s Way (1993)

De Palma teamed up twice with Travolta to good effect, but his efforts with Pacino proved even more fruitful. Indeed, the combination of De Palma and Pacino is close to cinematic nirvana.

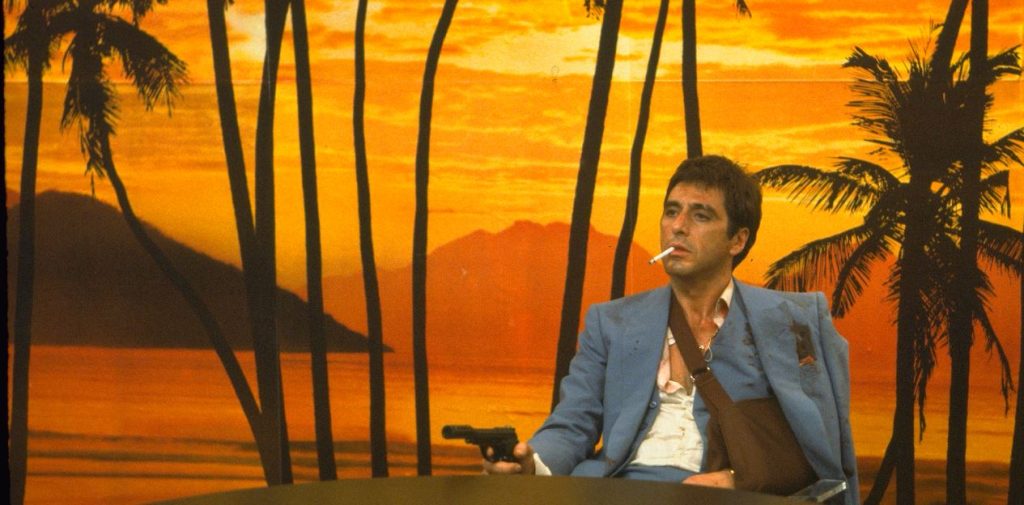

The Miami-set Scarface is arguably peak De Palma. It’s one of those flicks where everything from the script and casting to the direction and electronic score come together to create not only a believable world but a key moment in pop culture. Hated upon release by many critics for its violence, extreme profanity and uncompromising depiction of excess, the brightly lit Scarface has very much had the last, coke-fueled laugh.

“Most of my movies are about megalomania and guys living in insulated universes and the crazy things that happen within those universes, which is something that continues to fascinate me,” the director reveals in De Palma.

And thank God for that coz Scarface remains an essential and highly influential gangster flick. Pacino plays Tony Montana, a scummy, fast-talking Cuban immigrant whose depth of ambition makes Macbeth look timid and unimaginative. This is a guy with ‘steel in his balls’ who ‘wants the world and everything in it.’ Nothing proves a deterrent whether it’s watching a mate being chain sawed to death or an alleged informant’s dramatic plunge from a helicopter with a noose around his neck. Montana’s going to get it all, including the boss’ wife, a humongous bathtub, a small mountain of coke, a gaudy dress sense and a pet tiger. Even his younger sister (and her monstrous perm) are within the sights of this rapacious man.

Montana has a code, though. Or as he tells one powerful Bolivian drug lord: “All I have in this world is my balls and my word and I don’t break ’em for no one.” It’s this code that provides the one point in his favour in that he won’t kill women and children. That’s why the only person allowed to disrespect him in the entire flick is his honest, hardworking mum. Elsewhere, he’s ceaselessly impatient, arrogant and contemptuous, a mini-volcano of unrepentant criminality capable of erupting at any second. Pacino’s superb, ensuring Montana takes his place among the twentieth century’s best movie villains.

De Palma confidently constructs this poisonous package, adding black humour and surreal touches wherever necessary, such as an obnoxious immigration officer asking the newly arrived Montana: “What about homosexuality, Tony? You like men? You like to dress up as a woman?” De Palma goes on to nail the big set-pieces, especially the aforementioned chainsaw dismemberment in which he expertly builds suspense by allowing his camera to drift away from an awry drug deal inside a beachfront hotel to linger on a beautiful blonde in a bikini distracting Montana’s backup crew on the street.

I also like a brief scene in which our main man has survived a nightclub assassination attempt and is reaching toward a sleeping Michelle Pfeiffer. De Palma frames the shot so Montana’s bloodied hand is in the bottom right corner, enabling us to appreciate the quality of the bed’s satin sheets draped over the supremely elegant Pfeiffer. This is Montana in a nutshell: leaving a trail of blood while grubbily pawing classy things he has no right to.

De Palma gets most things bang on the money in Scarface, but immediately makes a mistake in Carlito’s Way. Or at least it starts in a way I’m not thrilled about by showing Carlito’s dying moments. Why on Earth do filmmakers think it’s a good idea to begin at the end? I know when you’ve been creating art for a while there’s a desire to mix things up, to reinvent, to play with structure, but this start-with-the-ending is not among my faves. It’s about the only criticism I can make of the brilliant Sunset Boulevard which commences with William Holden floating face down in a swimming pool. Now I’m sure it amused Billy Wilder to have a dead man narrate his tale, but it still spoils things by showing where things end up, you know?

Anyhow, I can forgive De Palma’s suspense-thinning decision as Carlito’s Way rapidly gets stronger. Sure, it’s another crime don’t pay tale, a setup as old as the hills and already covered by De Palma himself in Scarface, but it’s all about the way it’s told. De Palma ensures Carlito is no Scarface clone in that the two have quite a different feel. Tony Montana is so electric it’s like he’s giving off sparks, a bold, ruthless man who advances through animalistic cunning and chutzpah. He truly believes the world will be his one day. The Puerto Rican Carlito is cut from the same cloth but is more intelligent, thoughtful and evolved. Time and experience have wearied him. He knows a bullet will find him on New York’s mean streets if he tries to pick up his post-prison life where he left off. He simply wants to find a quiet place far from the madding crowd and concentrate on the better things in life. Indeed, he tells his girlfriend: “You don’t get reformed. You just run out of wind.”

Carlito is notable for its melancholy, fatalistic nature. Acknowledging he’s wasted too much time, Carlito wants to get into a position where he can make up for past mistakes. Unfortunately, he’s in a similar position to the aging Michael Corleone in Godfather III in that just when he thought he was out, he gets pulled back in. “I don’t invite this shit,” he says. “It just comes to me. I run. It comes after me.”

Pacino put away his shouty side for most of Carlito, an unfortunate aspect of his acting that began in the late seventies, and gives a calm, nuanced performance. With his black leather coat, well-trimmed beard and genuine love for his girl, he not only allows the character to breathe but comes perilously close to making him sympathetic.

As good as Pacino is, no analysis of Carlito would be complete without mentioning Sean Penn. Now one thing the movies teach us (apart from trannies being homicidal nutters) is that lawyers are slimy shits. Penn’s David Kleinfeld is one of the best examples you’ll ever find. Good grief, he’s a self-interested, treacherous cunt. Penn (barely recognizable beneath a frizzy, thinning hairdo) paints a memorable portrait of a man drowning in his own greedy, coke-tainted sweat.

Carlito has an expansive, post-Goodfellas feel that boasts an even better supporting cast than Scarface. David Koepp’s script deserves acclaim, especially the way its threads come together to illuminate such a fascinating patch of criminal darkness.

And De Palma? There are no split-screens or three-sixty pans here. Instead, he quietly holds everything together before delivering memorable sequences like the pool hall betrayal and the climactic train station shootout.

The mediocre monster hit: Mission: Impossible (1996)

I’ve nothing against the mainstream (e.g. Jaws, Star Wars or Raiders), but I do struggle with big-budget, obvious-attempt-at-a-blockbuster, let’s-have-a-franchise kind of thing. You know, the sort of mindless stuff where characterization is jettisoned in favour of insane, high-octane stunts every ten minutes or so. The $80m Mission: Impossible pretty much fits such a bill, except it’s hard to follow and a little short on action. The whole thing never clicks into gear. Decent actors like Jon Voight and Ving Rhames don’t make an impact. De Palma earns plaudits for the taut sequence inside a hi-tech, heavily protected CIA vault (complete with vomiting, an inquisitive rat and a falling bead of sweat), but otherwise it’s a talky load of po-faced, sub-Bond silliness, as exemplified by the face-removing.

Nevertheless, The Tom Cruise Show, sorry, Mission: Impossible, still grossed almost half a billion worldwide to become far and away the biggest hit of De Palma’s lengthy career. An Indian summer, all right, but his next two big-budget efforts (Snake Eyes and the $100m Mission to Mars) flopped. This led to smaller scale flicks in the new century, such as The Black Dahlia, that reaped neither reward nor respect. In all likelihood Carlito is likely to be his last hurrah, meaning he’s helmed far more washouts and mediocrities than hits.

His critics might point to such a conclusion as showing De Palma (and his bag of flashy, prurient tricks) mostly failed.

But here’s my tart little point: You don’t judge an artist by the depth of his or her lows or how many lows they’ve had. You judge them by their highs so if you ever hear anyone sniggering over Bonfire of the Vanities or trash-talking De Palma as some tasteless Hitchcockian rip-off merchant just offer this three-word rebuttal: Carrie and Scarface.

And then pour a bucket of pig’s blood over them.