Lines and shadows, shadows and lines. The Fountainhead is all sharp angles defined by shadows defined by shadows so sharp they could cut through the self-servicing philosophy of the artless Rand on the airless moon. Only one director could have made sense of this!!! King Vidor of Galveston Texas. He cut through the angles when he ventured through the lines and shadows. This is art, dagnabbit.

He traded in his Kodak Brownie for a Mitchel viewfinder and ventured forth among ’em. The lines are the boundaries separating the creative hard-charging creative thinkers from the rest of us lazy slubs leeching off them. There, I said it and I am glad.

The novel opens with Howard Roark stripped naked standing atop a giant outcropping of granite, laughing. “Ha Ha.” (Rand’s schoolgirl symbolism is as lacking in charm as it is obvious. Rand describes Roark standing naked and erect next to a pool of water like a kid who has just discovered masturbation.) Seems he just got booted from architecture school for talking back, failing to be mediocre and, worse of all, failing to conform, The dude was asking for it.

The film opens with Roark’s back to the camera, partly hidden in shadows, getting his ass reamed by the architect college dean for thinking he is better than other students. We learn the entire architectural world is enthralled by the Classics. Every architect designs buildings like those of Ancient Greece and Rome, just like Washington DC (I guess not the Pentagon. It doesn’t count because it is across the river, I guess). He gets the boot (“And don’t come back, asshole!!!”)

We move onto the one bright light in this dreary elitist bombardment, Henry Hull as an old-time architect who was making enemies in the building world long before this Roark upstart was born. He hires our hero after an abusive lecture then croaks after passing the sputtering torch to our Howie.

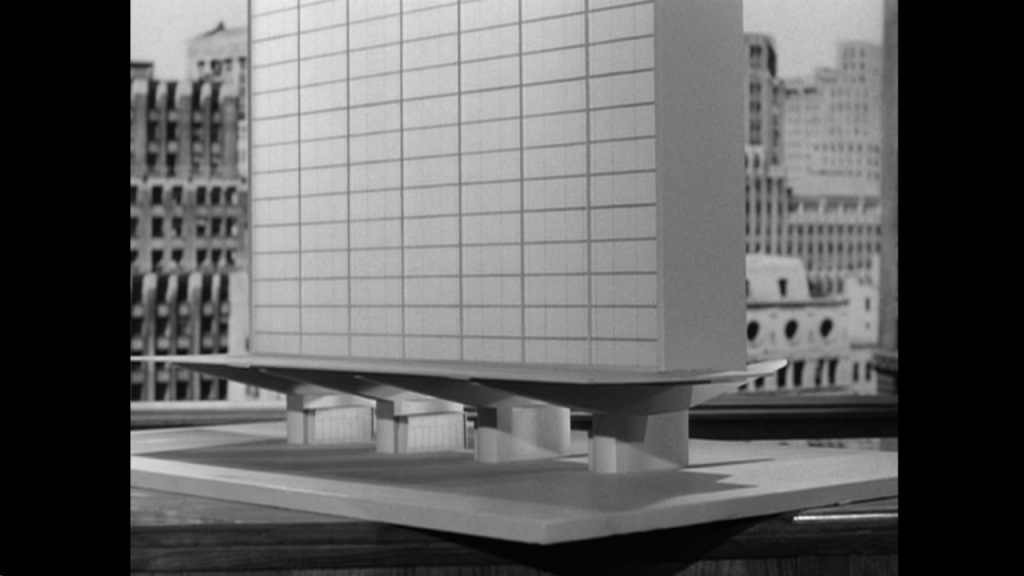

Time passes. Howie gets a job to design a new headquarters building for a bank or insurance company or something like that. We see a model of his design; a matchbox on stilts. The board of directors tell Howie he has the job, if he will agree to add a bit of classic eyesore to the pristine matchbox.

He thinks it over. Like, he really needs the money. His subscription to Architectural Digest is about to expire and he needs money to renew. Shoot! Howie says… No!

Witnessing this humiliation from the shadows is the architect of Howe’s downfall, one Ellsworth M. Toohey, dreaded architectural critic for the leftist rag, The Banner. He is a socialist who hates independent minded guys like Howie (Ellsworth’s poor attitude might be attributed to the fact he had the crap kicked out of him every day K through 12 for having the name Ellsworth. He is actually better off than the owner of The Banner, Gail Wynand, played by a grumpy Raymond Massey.)

Toohey is a guy who flunked out of art school and is envious of guys like Roark who design boxes on stilts and always get the girl. His revenge is to ruin the life of a guy like Roark. He may just be a commie. Rand hated commies.

Now we come to the core problem of the silly narrative. The idea that architecture is of even the slightest interest to most newspaper readers. The idea that the average Joe gives a rat’s ass about building design. Average Joe’s interest generally goes no further than free parking, unless he is a construction worker.

Since he finds no employment as an architect, Howie signs on as a laborer, which enables him to meet the wealthy, regally beautiful Dominique Francon, played with regal beauty by Patricia Neal.

Wealth and beauty are meaningless to the emotionally dead Dominique. She tried reading Forever Amber, but it didn’t take. She just needs the right man to awaken the furious emotion lying dormant. You don’t have to jump ahead to see just who is waiting in the wings to take on that task. Yes, the Prometheus of the marble quarry. When they finally get to it, the romance has all the maturity of a couple of kindergartners, without innocence.

An old school chum of Howie gets the commission to build a housing project he doesn’t have the chops for. He begs Howie to design it for no credit. He agrees with one condition. Not one change. It will be built with nothing added, or subtracted or changed. Final cut. Agreed.

Well, you know how good a pinko’s word is. The project gets built and not how Howie wanted, so he blows it up. That’s right, vandalism in the name of the superior man. Howard Roark: Ubermensch.

As you might expect he is arrested and tried for his crime. His only defense is a speech to the jury consisting of some horseshit about the man who discovered how to make fire was burned at the stake for his efforts, and other arguments on why he was better than everyone else. Keep in mind the only building he actually designed and was built, he destroyed. Tell me again, just why is he an Ubermensch?

After a few minutes of this banality, he is found not guilty and is almost carried from the courtroom onto the shoulders of the spectators.

On the basis of this Uber-arrogance, he is awarded a commission to build the highest building in the world. Yeah well, bigger is better.

To say the dialogue is stilted and the characters are cardboard is to be kind, but considering they are in aid of this shallow, crypto-fascist story they seem appropriate.

Humphrey Bogart wanted to play Roark. There has been talk of a remake with Brad Pitt as Roark. The film would have been much more palatable with tough guy actor Lawrence Tierney, just off Born to Kill, as “Mad Dog” Roark. That sissy critic Toohey would have been found beaten to death in front of The Banner office, and no one would dare change a line of any of Roark’s blueprints.

Roark has several spiritual descendants. Michael Cimino, Quinton Tarantino, Jack Reacher, Donald Trump, and the like. That way lies madness. Tell the children.

Oh, at the end, Roark makes Dominique’s emotion acute. You knew he would.