Since M. Night Shyamalan’s much ballyhooed 1999 feature The Sixth Sense, twist endings have gotten something of a bad rap, and usually with good reason. After all, in many cases they are a cheap way to add excitement to the climax of an otherwise dull story. Sometimes they are a cop-out, negating all emotional involvement that may have been invested in a movie up until that point. Others seem to be the sole reason for a story’s existence, without which the whole thing crumbles. On the other hand, when they work, twist endings can make a good film great, and they occasionally even reward repeat viewings by revealing previously unseen layers that can only be recognized once the conclusion of the story is known. The Sixth Sense is indeed a good example of a movie that holds up well even after the twist is known, revealing itself to be deeply sad and beautiful beyond the mere thrills of the first viewing.

As rightly reviled as are many recent examples of the technique, especially many of Shyamalan’s subsequent efforts, there are also many laudable examples to be found among some of history’s greatest cinematic achievements, old and new. Widely respected filmmakers from Alfred Hitchcock to David Fincher and Christopher Nolan have successfully employed the well-placed twist to wonderful effect, and even Orson Welles’s immortal classic Citizen Kane, considered by many to be the greatest American film ever made, concludes with what can be deemed an elegant, emotionally rich twist ending.

Now would be a good time for the inevitable “spoiler” warning. In the following paragraphs we will be discussing various types of twist endings and how they have worked (or not) in a variety of different films. By the very nature of such a discussion, key plot elements will necessarily be revealed, so the reader is hereby advised to have seen the following films before proceeding: The Lady Vanishes (1938); The Wizard of Oz (1939); Citizen Kane (1941); Suspicion (1941); Alice in Wonderland (1951); North By Northwest (1959); Carnival of Souls (1962); Angel Heart (1987); Presumed Innocent (1990); Jacob’s Ladder (1990); A Pure Formality (1994); The Usual Suspects (1995); Primal Fear (1996); The Game (1997); Fallen (1998); The Sixth Sense (1999); eXistenZ (1999); Fight Club (1999); American Psycho (2000); Memento (2000); The Others (2001); Adaptation (2002); Oldboy (2003); High Tension (2003) Identity (2003); The Life of David Gale (2003); The Village (2004); Stay (2005); Derailed (2005); The Prestige (2006); The Illusionist (2006); Fracture (2007); Law Abiding Citizen (2009); Dogtooth (2009); Shutter Island (2010); Inception (2010).

One type of twist ending, which is as good a place to start as any, is what I will call the “unacknowledged death” twist. As seen in The Sixth Sense, this is the revelation, usually at the end of the film, that one or more characters has been dead all along, or at least from some point in the story onward. The Sixth Sense got a lot of credit for this particular twist, though it had actually been done numerous times before, even as early as Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls in 1962. At the time of that film’s release, this was undoubtedly a shocking turn of events, but after seeing basically the same twist in so many subsequent films (including Alan Parker’s Angel Heart, Adrian Lyne’s Jacob’s Ladder, and Giuseppe Tornatore’s A Pure Formality), it is difficult not to see this one coming. Perhaps viewers in 1999 either hadn’t seen or had forgotten these and other earlier films with the unacknowledged death twist, a forgetfulness that contributed to The Sixth Sense‘s huge success, but later films like Alejandro Amenabar’s The Others undoubtedly suffered from Shyamalan’s reintroduction of this type of twist into the popular consciousness.

The biggest problem with the unacknowledged death twist is its strong tendency to be the story’s sole reason for existence. As mentioned before, this is one of the primary reasons a twist can fail. The best of these types of movies can be fun to rewatch in order to spot the little clues that were there all along, but they mostly lose any repeat viewing value once the outcome is known. The same can also be true of movies that take the opposite route, revealing a character presumed dead to actually be alive. Again, this twist is very commonly employed and can work wonderfully when it is not the story’s only interesting aspect, as in, for example, Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige, in which the final twist only adds to the expertly crafted intrigue that came before. When, on the other hand, there absolutely is no story without the final twist, we end up with a movie like Neil Burger’s The Illusionist (the “other magician movie” of 2006). This film, while well-made and filled with strong performances from the likes of Edward Norton and Paul Giamatti, not only relies entirely on its twist ending, but also telegraphs the twist so obviously that even the ending isn’t satisfying, especially when its style so closely apes that of better movies like Bryan Singer’s The Usual Suspects.

The unacknowledged death twist is often linked with two other types of twists, both very commonly used either alone or in conjunction with each other and/or the unacknowledged death twist. First, there is the “it was all a dream” twist, which is often reviled as the ultimate cop-out in filmmaking, but which also provided the conclusions for at least two of history’s best-loved fantasy films, The Wizard of Oz and Alice in Wonderland. The most interesting way in which a movie can utilize this particular twist without inspiring cries of “Foul!” from its audience is by not actually making the assertion that preceding events were just a dream, but rather keeping the true nature of reality ambiguous. Good examples of this include David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ and Christopher Nolan’s Inception; throughout each of these films we are repeatedly thrust into worlds we know to be merely fantasy, only to have the rug pulled out from under us in the end by plot devices designed to make us unsure what, if anything, has indeed been real.

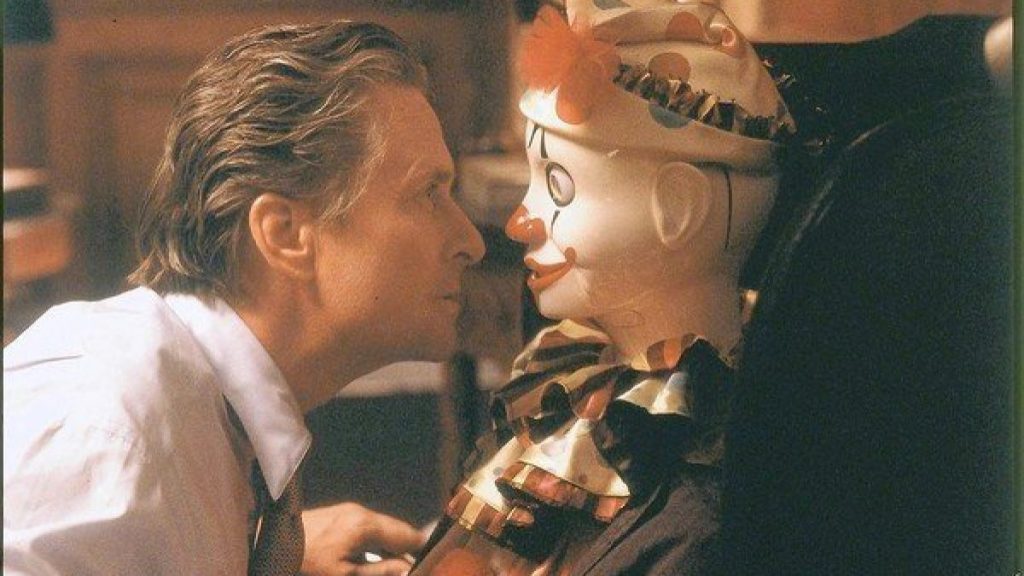

David Fincher’s The Game is another good example of this ambiguation, in which a third-act twist seems to reveal the extent to which all preceding events have been orchestrated in order to trick the main character, Nicholas Van Orton (Michael Douglas). When his brother, Conrad (Sean Penn), reveals that everything up to and including Nicholas’s accidental killing of Conrad and subsequent suicide attempt have all been part of the elaborate ruse, we think the final revelation has been made and we are either satisfied or angry, depending on our inclination. It is only in the final scene, when Christine (Deborah Kara Unger) invites Nicholas to accompany her for coffee before her plane leaves, that we begin to wonder if the game is truly over, or if it ever will be. This ambiguity provides a more satisfying conclusion similar to eXistenZ‘s final line, “Are we still in the game?” or Inception‘s final shot of the spinning top.

Marc Forster’s Stay is a beautifully atmospheric but ultimately frustrating film that combines the dream twist with the unacknowledged death one, presenting a mystery involving a suicidal young man named Henry (Ryan Gosling) and the gradual realization throughout the story that everything we as an audience experience as we struggle to stay ahead of the narrative (or at least keep up with it) is, in fact, the elaborate fantasy of Henry’s dying moments in the aftermath of a car crash we had presumed him to have survived at the start of the movie. When two paramedics at the scene, who were very close in the world of Henry’s fantasy, where they are known as Dr. Sam Foster (Ewan McGregor) and Lila Culpepper (Naomi Watts), meet each other’s gaze, Sam appears to “remember” their connection and asks Lila out for coffee. Many critics and audience members at the time apparently felt they had been had, and the movie was not successful, perhaps because of its similarities to movies like The Sixth Sense and The Game, or perhaps because it simply combined one too many types of twists: the unacknowledged death, the dream, and a third type that is very commonly employed, usually to better effect than the former two: the unreliable narrator.

Countless films throughout history have employed an unreliable narrator in one form or another, and the technique finds its ancestral beginnings in literature, in works such as Nikolai Gogol’s “Diary of a Madman” and Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper”, as well as more modern works like Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho. Indeed, Mary Harron’s film adaptation of American Psycho, starring Christian Bale as the unreliable narrator/protagonist Patrick Bateman, is a perfect example of the cinematic use of this twist. The revelation that Bateman’s supposed murder victim, Paul Allen (Jared Leto), is alive and well in Europe leads Bateman (as well as the audience) to wonder whether his entire murderous rampage throughout the film was really just in his head; whether “it was all a dream,” so to speak. Certainly this would explain how Bateman has been able to get away with his extreme, overt acts of violence for so long. The only other explanation would be a massive cover-up on the part of all of society, a far-fetched but intriguing possibility that fits in nicely with the film’s viciously satirical look at the privileges of wealth.

Another famous example of the unreliable narrator twist that has many other themes in common with American Psycho is David Fincher’s Fight Club, adapted from Chuck Palahniuk’s novel. After seeing the tricks Fincher pulled with his previous film, The Game, I remember initially watching this one with an especially careful eye and enjoying the gradual process of figuring out the twist early on, then second-guessing my intuition several times before the film reveals that its unnamed narrator (Edward Norton) and his idol and mentor, Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), are, in fact, one and the same person. Part of why Fight Club works so well is that, even if you see the twist coming, everything else about the movie is so satisfying that you aren’t disappointed. In fact, sometimes it can be fun simply to be vindicated when you think you are ahead of a movie (as is the case with the predictable but modestly enjoyable thriller Derailed), as opposed to the feeling of being cheated by a twist that is simply too silly or implausible to swallow (e.g. Fracture or Law Abiding Citizen).

The unreliable narrator twist as applied to the serial killer genre was brilliantly spoofed in a bit of dialogue in Spike Jonze’s Adaptation, written by Charlie Kaufman, a master of effective twists, surprises and ambiguities. In the movie, Charlie’s brother, Donald Kaufman (both played by Nicolas Cage), describes his screenplay, “Three,” in which a killer, his soon-to-be victim, and the cop pursuing him turn out to be one and the same person. Incredibly, this preposterously overwrought twist was pulled off to great effect (though most critics disagree) in Alexandre Aja’s High Tension, in which Marie (Cecile De France) appears to be both pursuing the murderous abductor (Phillipe Nahon) of her friend Alexia (Maiwenn Le Besco), and running the risk of being his next victim, until it is revealed in the third act that Marie is actually the killer, and that all the circumstances surrounding the murders and abduction are entirely a product of her demented imagination. A similar case in which this type of twist is taken even further is James Mangold’s Identity, in which the entire suspense story in which the audience has become invested throughout the movie is revealed to have taken place only in the imagination of serial killer Malcolm Rivers (Pruitt Taylor Vince). Other movies that employ the unreliable narrator twist, to varying degrees of success, include Gregory Hoblit’s Fallen, Christopher Nolan’s Memento, Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island, and of course, the aforementioned Usual Suspects.

This brings us to the fourth major type of twist, what I like to call the “guilty after all” ending, which is a pretty self-explanatory way to put it. In a way, it is a variation on the “it was all a dream” twist, but instead of the entire reality of the film’s narrative being shattered (or at least called into question), this type of movie presents us with a seemingly guilty protagonist who we are led to believe is actually innocent, only to find out that they are in fact guilty of the crime of which they were originally accused. However, in most cases, their guilt and the motives behind it are not quite what they initially appeared to be.

A good example of this is Gregory Hoblit’s Primal Fear, in which an altar boy named Aaron (Edward Norton) is accused of murdering a priest. His attorney, Martin Vail (Richard Gere), digs deeper and finds that Aaron has developed a split personality due to trauma caused by physical and psychological abuse at the hands of the priest. He uses this information to win the case in Aaron’s favor, only to find out at the story’s conclusion that he has been manipulated by Aaron, whose split-personality has been merely an elaborate ruse designed to bring about this precise outcome. An even more far-fetched example would be Alan Parker’s The Life of David Gale, in which the title character (Kevin Spacey) turns out to have conspired with his supposed victim (Laura Linney) to sacrifice their lives in order to make the point that the death penalty sometimes claims the lives of innocents.

This category of twist can be expanded to a broader definition, including movies in which the truth is revealed to be startlingly close to what is assumed from the beginning, such as Alan J. Pakula’s Presumed Innocent, [EDITOR’S NOTE: One of the greatest works of fiction ever] in which Barbara Sabich (Bonnie Bedelia), the wife of the accused attorney “Rusty” Sabich (Harrison Ford), turns out to be the culprit, having inadvertently framed her husband under the assumption that he would recognize her guilt and use his influence to cover for her. This category can also be stretched a bit to include movies like the aforementioned Fracture and Law Abiding Citizen, in which the guilt of the murderer (Anthony Hopkins in Fracture, Gerard Butler in Citizen) seems certain from the beginning and the twist reveals not “who” but “how,” which in both of these examples involves a godlike omniscience on the part of the criminal masterminds that strains credibility, to say the least.

Another interesting take on the “guilty after all” twist (which I have written about at length elsewhere on this site) is ambiguously found in Alfred Hitchcock’s Suspicion, in which Lina (Joan Fontaine) spends most of the movie convinced that her charming new husband, Johnnie (Cary Grant), is secretly plotting to kill her. Of course, in the end she is found to be mistaken, though the way in which this is proven is flimsy at best (it’s really just Johnnie’s assertion that he was actually considering killing himself that convinces her), and in the end Johnnie comforts her with a small, secret smile. On the surface, this seems to be merely amusement at the absurdity of her assumptions, but knowing Hitchcock’s prankster sensibilities, it is easy to imagine him directing Grant to convey something darker with this expression. Even if taken on face value, the film has a clever twist ending that fits rather well into this broad category.

Finally (at least for the purposes of this discussion), there is the fifth major type of twist ending, which involves a conspiracy, the revelation of which explains the mystery at the center of a film’s plot. Good examples of this type of twist include Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes and North by Northwest, to name just two (Hitch was particularly fond of this type of twist). “Conspiracy,” of course, is not necessarily meant to imply a vast, far-reaching intrigue involving dozens of people (or more); while a movie can certainly tackle a subject this large, many stories that utilize the conspiracy twist only involve two or three participants. The aforementioned Derailed, for example, concerns an elaborate extortion plot largely carried out by only two people, Lucinda (Jennifer Aniston) and LaRoche (Vincent Cassel), one of whom seems to be a victim herself until the conspiracy is revealed. On the other hand, The Game, previously mentioned as an example of the “it was all a dream” twist, is also a good example of a vaster conspiracy involving dozens of participants.

To return to a contemporary filmmaker known perhaps more than any other for his (over)use of the twist ending, M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village involves the conspiracy of the town elders to convince its inhabitants that they live in an antiquated, presumably 18th century settlement. It is only at the end, when young Ivy Walker (Bryce Dallas Howard) manages to escape the parameters of the village, that we realize the entire story has actually taken place in the present day. This conspiracy is so elaborate, requiring generations of people to perpetuate its premise in total isolation from modern reality, that it certainly strains credulity. However, a more recent and far superior movie, Giorgos Lanthimos’s Dogtooth, posits a very similar situation to far greater effect with one key difference: rather than a third-act twist, the surreal fantasy world in which this film’s “family” lives is gradually revealed to the audience right from the very start, developing with depth, subtlety, and humor until the haunting conclusion.

It is not uncommon for an overly contrived twist to ruin an otherwise interesting movie. Derailed is, again, a perfect example of this; without the rather predictable twist that Lucinda is actually in league with LaRoche, we would have the potentially much more satisfying story of the horrifying consequences of a marital transgression between two ordinary people. Unfortunately, the more the conspiracy is revealed throughout the movie, the less invested we become in the story. Instead of honest emotional identification with the characters, we become passive observers of a clever game. Conversely, a twist works when it develops naturally from the story, which in turn develops from the actions of strong characters.

It is difficult to pin down exactly what makes a twist work or not, and of course this is highly subjective; a twist that captivates one viewer might seem absurd and unintentionally comical to another. However, there is a vast difference between the third-act revelations of, for example, Chan-wook Park’s Oldboy and F. Gary Gray’s Law Abiding Citizen, and this is not because Oldboy‘s plot is any less contrived or difficult to believe; it is because what has come before the twist in Oldboy has made the viewer identify with its characters, and thereby become more invested in their situations. Additionally, what happens after the twist is important. Whereas Citizen seeks to tie up all loose ends with a preposterous solution, Oldboy leaves the viewer with a lingering and uneasy sense of ambiguity over what will become of Dae-su Oh (Min-sik Choi) and Mi-do (Hye-jeong Kang) now that the twist has been revealed.

It is this sense of ambiguity, along with fully realized characters and a well-constructed story, that deepens and enriches the truly great movie with a twist ending. The example of Citizen Kane mentioned at the beginning of this essay was not meant to be facetious. Kane is, by all definitions, a movie with a twist ending. However, the revelation of what “Rosebud” actually is means nothing in and of itself; it is only by taking the journey of empathy through the film’s narrative that we feel the impact of just what that long forgotten sled means (or doesn’t) to the life of Charles Foster Kane. In other words, when a story works backward from a clever twist, it usually shows, whereas a motivated twist that potentially raises questions while answering others is infinitely more satisfying.