All young men have had such fantasies. Hell, I’m not so sure the desire ever leaves, unless of course we are of advancing middle-age and our only options are women who, at best, resemble our grandmothers. I am speaking of the lust we might hold for an older woman. When we are young men, full of idealism, passion, and a need to screw anything that moves, older women are seen not only as experienced sexually, but as the holders of great wisdom and dignity; a direct contrast to the vapid ninnies that are the vast majority of teenage girls. This yearning for a woman of keen intellect and worldly delight is, of course, wholly dependent on our comparable abilities, for it is unlikely that the captain of the football team requires philosophical examinations and existential ruminations.

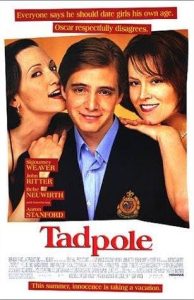

Oscar (Aaron Stanford) is just such a lad. Erudite, wise, and preoccupied with Voltaire, he holds out hope that he may indulge in his need for an idealized older woman. Such matters are complicated by the fact that she, Eve (played by Sigourney Weaver), is Oscar’s stepmother. The story begins as Oscar is home for Thanksgiving break to visit his father Stanley (the always charming John Ritter) and his new wife. Stanley is a professor of history, Eve a medical researcher, and Oscar the shining product of such a stellar environment. As an example of Oscar’s obviously different needs, he is approached by a tartish young school chum on the train home. While most young boys of fifteen would be soiling their jeans at such an opportunity, Oscar is immersed in Candide, pausing only to notice that the young girl does not possess the hands of a great woman. Oscar is just that sort of romantic. He wants more than the average girl his age can give. He wants his stepmother.

Oscar’s world is one of dinner parties with his father’s colleagues, private schools, and yes, friends of the family who desperately want to sleep with young Oscar. The woman in question, Diane (Bebe Neuwirth), flirts with young Oscar as the film opens and within a matter of minutes, has him on her chiropractic table with his shirt off. After much drinking and innuendo, the two end up in the sheets, although this is not enough for dear Oscar. Diane is older, yes, but not possessing the elevated gifts of his deepest fantasies. She is not his stepmother. Oscar even manages to get several phone numbers from Diane’s girlfriends, but he is disinterested at best. And yes, it was at this point I most felt the film’s unreality. One may pine for the one holy grail of older women, but it is inconceivable that any teenage boy is going to resist the advances of other older women. It would have been far more gratifying (and in touch with the world as we know it), had Oscar bedded each and every one of these 40-ish ladies, and dammit, I wanted to witness it all. Is that asking too much?

Of course, Oscar wants to keep his liaison with Diane a closely guarded secret, but all is revealed at a farcical dinner at a restaurant. The scene is full of a frantic, desperate humor, and it was one of the undeniable pleasures of the film. Eve is stunned, and doesn’t quite know how to deal with Oscar after the affair is out in the open. One could argue that she would be properly disgusted, but because this is Oscar’s story, we know that deep down, she is (albeit reluctantly) slightly curious. After all, Eve is charmed by Oscar – they share literary discussions and speak in tones usually reserved for university roundtables. She seems content with Oscar’s father, but as in all cinematic marriages of this type, there is a “hole” that prevents true and absolute happiness. Oscar just might be the key that unlocks her moribund marital state.

It would be nasty of me to reveal the outcome of this dilemma, although I can say that the result is gently satisfying because it ends as it should. Still, I do have a problem with one aspect of the conclusion, in that Oscar is seen as “redeemed” by a new found interest in the very type of girl who so bored him at the beginning. The young lass on the train appears again as Oscar returns to school, only this time she is armed with a handy quote from Voltaire. It is certain that this girl merely memorized a bit of the Frenchman’s work in order to get into Oscar’s pants, but that seems to be enough for him. We can imagine that the filmmakers are implying that Oscar must (and will) forego his attraction to older women and begin to accept girls of his own age group. Why must this be so? Oscar was our screen champion; a boy who desired stimulation of the mind and body that only a seasoned woman could provide. Teenage girls might do the trick in the back row of a movie theater, but they will never exchange the sorts of knowing glances that come when two people have entered a distinctly higher plane. We wanted then (and want even today, regardless of age) the carnal and the scholarly; orgasms and poetry.

At 77 minutes, Tadpole is both quick and light as a feather. It is fine entertainment, but lacking true depth and quality (filmed on digital video, it is often blurry and unfocused). There are genuine laughs to be found and the performances are sharp (Stanford is a keeper). Still, I wanted Oscar to keep his dreams alive and continue in his quest to find the perfect woman. At 15, he is unlikely to find such things among his peers. Personally, I was a loser all-around at that age, but I too felt the tug of the “woman” – deep, insightful, sophisticated, even married with a family – that surpassed even the hottest of young flesh. For while I would have sold my mother to bandits in order to have quick, mindless sex at that age, it would have taken an Eve to keep me around.