At the risk of gaining a reputation as some sort of lunatic who insists on reading way too much into the subtext of popular 80s movies, the 1985 werewolf movie Silver Bullet is about priests molesting children.

The “priest” in question here is actually a Reverend, which indicates he is not in fact a Catholic priest, and the abuses perpetrated and covered up by the Catholic Church only began to come to light a few years after this movie was released, but the metaphor is there if one is looking (and also possibly some sort of lunatic). Stephen King, who wrote the screenplay as well as the novella on which it was based, has written harrowingly of child abuse in many of his works over the years (The Library Policeman, Gerald’s Game), and his mistrust of religious zealots has likewise cropped up early and often throughout his oeuvre (Carrie‘s mother, Mrs. Carmody in The Mist, etc).

The werewolf myth (along with its kissing cousin, Jekyll and Hyde) is ripe for interpretation as a metaphor for any sort of secret life or struggle against evil impulses, and King has also written about this sort of subtext at length in his non-fiction works (as well as stating that he did not realize The Shining was about his own alcoholism until after he had written it), so perhaps this interpretation is worth exploring even if it was not his original intent.

Reverend Lowe (Everett McGill) is introduced early in the movie, but made to seem unimportant, the camera moving away as he begins his sermon to find paraplegic adolescent Marty Coslaw (Corey Haim) playing a prank on his sister, Jane (Megan Follows). It might seem harmless enough in a Tom Sawyerish way, though it does involve terrifying her with a snake, but it could also be seen as the sort of acting out often done by abused children, indicating that the molestation has already begun.

The first few murders have a sort of Old Testament righteousness to them, as later justified by Lowe himself: the hopeless drunk put out of his misery, the pregnant woman saved from the mortal sin of suicide, and especially Milt Sturmfuller (James A. Baffico), the possibly abusive father of Marty’s friend Tammy (Heather Simmons). He appears almost jealous when Tammy kisses Marty in front of her house, and is obviously meant not to be mourned after he voices his belief that “damn cripples” like Marty should all be electrocuted in order to “balance the goddamn budget,” but we do not see the extent of his abusive nature. Tammy is afraid of the shed in her backyard, ostensibly because of strange noises she has been hearing from it, but the subtext could be that this is where her father abuses her in some way. When he is murdered in said shed, perhaps it is the Reverend doing penance for his own similar crimes against children.

The killing of Marty’s friend Brady Kincaid (Joe Wright) breaks the Reverend’s pattern of righteous or justifiable killings. Marty is reluctant to leave Brady alone as he goes home, which makes sense given the fact of the murders that have taken place in the town by now, but it may also indicate the shared secret between the two boys and Reverend Lowe. We never actually see what happens to Brady, just the bloody kite in the aftermath of his death. Perhaps he threatened to expose the Reverend as the child abuser he is, and was killed in order to protect the secret. Whether Lowe is abusing other children besides Brady and Marty is unknown; it could be that Brady is the only one he sees as a threat at this point.

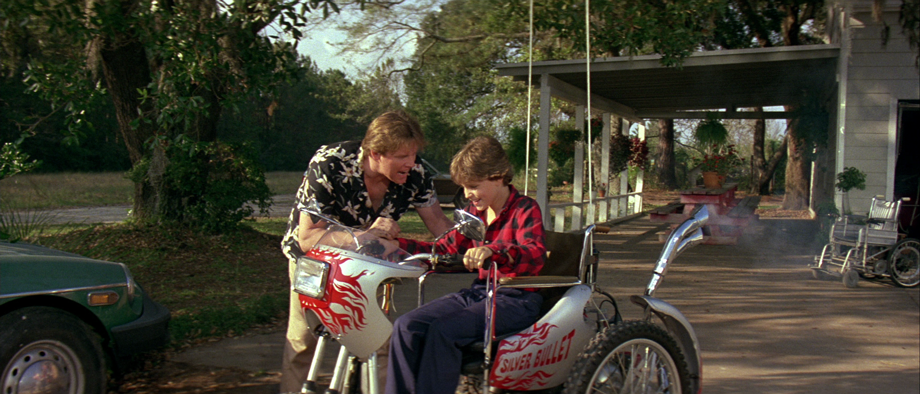

Marty’s Uncle Red (Gary Busey) seems to be his primary male role model; despite the fact that his parents are together, we see much more of Red than we do of either of them, especially his father, Bob (Leon Russom). His mother, Nan (Robin Groves), Red’s sister, disapproves of Red’s permissive attitude, which might make him ripe for victimization, as she says, “He already has so many strikes against him.” Marty ultimately encounters Reverend Lowe in full werewolf mode because of this permissive attitude, as he is out shooting off fireworks Red clandestinely gave him, but is ultimately saved by the same, as he uses a firework to put out the werewolf’s eye, then escapes in his “Silver Bullet” motorized wheelchair, another indulgence from Uncle Red. This could be seen as symbolic of the debate over whether permissive attitudes toward sex and other freedoms are more or less conducive to potential victimization of children.

Red doesn’t believe Marty at first, and even after he has convinced Jane, she doesn’t think to suspect Reverend Lowe even as she scours the town for a recently one-eyed man. The abusive, monstrous priest gets away with it for so long because he is such a trusted moral figure, which makes it all the more shocking for a good Christian girl like Jane when she discovers him with the damning eyepatch. With Jane’s help, Marty writes and sends anonymous letters to the Reverend that read like what any child abused by his priest might write: “I know who you are. I know what you are. Why don’t you kill yourself?” When Uncle Red finds out about this, he is upset that the kids are harassing the Reverend, who he assumes must be innocent. The adult’s denial of something too horrible for him to conceive is another way in which the insidiousness of the priest’s abuse continues unchecked.

In addition to the sort of righteous killings he justifies to Marty when he corners him in the old covered bridge, Reverend Lowe has also already killed to protect his dark secret, when he slaughters the vigilante group after the murder of Brady Kincaid, and he clearly means to do it again in this rare daylight attack, the line blurring between man and monster. “I would never willingly hurt a child,” he says ironically as he advances on the helpless Marty, who pleads in the cry of the abused, “I won’t tell anyone!” Luckily another adult is present when Marty needs one, and the Reverend must flee without harming him further.

If we replace the specific word “werewolf” with the more general “monster,” the universality and openness to interpretation of the werewolf myth becomes clear. “In the made-up stories,” Jane says to Uncle Red after he finally comes around and agrees to help, “the monster only changes when the moon is full, but maybe he’s like this almost all the time.” When Uncle Red asks Marty how Lowe became a monster, Marty replies, “I don’t know. Maybe he doesn’t know, either.”

A man who periodically becomes a monster, who commits monstrous acts, ultimately is a monster in totality. There is no pity to be found for the monster here, as in The Wolf Man or An American Werewolf in London. Even his nightmare sequence is not one of remorse, but of being exposed and punished for his crimes by the community he has victimized. Ultimately this fear is realized, though the world will never know the true extent of his monstrosity. That knowledge is left only to one of his surviving victims, and the few people with the courage to believe him.