The American cinema never really deserved the likes of Robert Altman, a man who never made the same movie twice, even when detractors accused him of coasting on his reputation. Sure, he largely disappeared in the 1980s (except for the wonderful Secret Honor), and even after his comeback with 1992s The Player, he still made us suffer through Ready to Wear and The Gingerbread Man, but as he said of himself, he never made a movie against his will. His projects were his own, and even when we wondered what he was thinking, we still saw in his choices the rebel of old; a gifted iconoclast who, above all, respected his audience enough not to always draw straight lines.

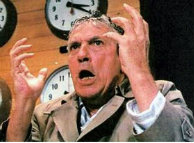

He was a salty, snarling old bastard wonderfully so and more than single-handedly reinventing how we listen at the movies, he dared bring us real life in a medium accustomed to contrivance and artificiality. And with his death an old, tired man to be sure, but always, always too soon we have not only lost a unique, irreplaceable voice, but an unrepentant S.O.B.; the kind they couldn’t make again if they tried. And believe me, they ain’t trying.

My love affair with Altman began on a snowy December evening back in 1993. I drove through a raging snowstorm to watch the epic Short Cuts, expecting a good film (I had recently seen The Player), but unaware that I was about to witness true genius behind the camera. Here was a man who told dozens of stories in brief, fleeting snippets; all with such unvarnished clarity that they left me floored. I knew of his reputation, having read reviews of his work (primarily Roger Ebert and Pauline Kael), but until this night, I could not fully appreciate his unparalleled understanding of humanity. This, I knew, was how people communicated with each other the interruptions, the pauses, the backtracking and every other work seemed hollow and false by comparison.

And yet, despite the heavy subject matter (though always tempered with a biting wit), Altman always managed to avoid that sanctimonious sneer that afflicted the less gifted auteur. This was the stuff of life, yes, but he wasn’t about to deliver a sermon. Whatever connections were to be made and there were always too many to count; they were ours alone. If we recognized or failed to recognize ourselves in these films, responsibility was never his, and spoke only to our willingness to probe the very lives we led. Or thought we did.

From then on, through M.A.S.H., Nashville, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye, California Split, and 3 Women, he took a familiar genre or period, shook it around a bit, and gave us something completely his own, yet always more faithful to the truth of the situation. If we had been used to an untamed prairie of rugged lawmen and heroic cowboys, he’d rip away our illusions and demonstrate that beneath the phony idealism, the push West was little more than an orgy of capitalism made worse by cowardice and greed.

Instead of community, we had alliance; and all tough talk and standing tall would get you is good and dead, an event itself that would go unnoticed. And as our bi-centennial approached, he would spool forth the moral rot of the American Dream, and how a nation allegedly committed to fair play and freedom was instead teeming with pettiness, narcissism, and murderous violence. Throughout the 1970s, he peeled away our very skins, exposing the loneliness, the obsession, and the crippling insecurity that may have been heightened by Watergate and Vietnam, but was as much a part of the American experience as the so-called ideals we trumpeted on a daily basis.

And when it was time for him to die, he gave us A Prairie Home Companion, a surprisingly gentle ode to endings, from the insignificant radio show to life itself. It was the most fitting end to this man’s career, and one he had to know would be his last. The years will be kind to this closing chapter, but even now, so soon after I first saw it, I look back with fondness at its sweet, though unsentimental, rhythm; its effortless sweep through lives we couldn’t possibly know, but by the end, know all too well. Ill always treasure Nashville above all else for its scope and breadth of understanding, but emotionally, this one will be the keeper.

The fullest measure of a man should be knowing when to give up the chase, and no one on screen has ever said it better. We cling firmly, often ferociously, to the moments that make up our lives, but the admission that it’s over a marriage that can’t be saved, a once vibrant talent that’s ebbed too long, a body that cracks and groans with frailty is so inspiring as to be heroic. It’s what we do least often, but when it is done, it’s what we do best. Altman may not have chosen to die at this very moment, but I’d like to think that he did, for then he’d be living as he worked, dying as he created, and above all, calling his own shots. As always. Goat bless Robert Altman.

Leave a Reply