Steven Soderbergh’s Bubble is the first great film of 2006; a work of such deceptive simplicity and self-assurance that it makes even the commonplace appear fresh and exciting. It harkens back to a time of bold experimentation and artistic risk, but does so without the self-conscious flash and dubious merit. Assuredly, this is not a work that is instantly dated, or “of its time;” or a fashionable exercise that loses steam as it limps towards an incomprehensible climax. Instead, this is a film — banal and monotonous, though grandly so — that is not of these things, but about them; how our lives — especially in towns like the small Ohio hamlet of the film — become so routine, pointless, and dull that all we have left is the semblance of identity that itself becomes increasingly impossible to define.

Ego is all, especially in the midst of stupefying boredom, and every moment becomes less about survival (certainly not progress) than an opportunity to exert the fleeting, yet powerful, urge for control — over a situation, a moment, an action, or, more notably, another person. And it becomes even more obvious among those we see here — powerless, anonymous, and utterly inconsequential. Without a future, a purpose, or even a reason to get up in the morning, we are totally bereft unless we are, even to that one figure in the dark who might be unaware, important and necessary. Loneliness, then — that uniquely human, crushing sense of invisibility — becomes nothing more than not being a vital element of another’s very existence.

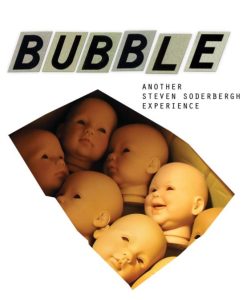

Martha (Debbie Doebereiner) is just such a woman. Living a life of pathetic insignificance with her ailing father, she is fat, awkward, and clueless about her surroundings. She literally has nothing, except of course for what she perceives to be a friendship with a young man (Kyle, played by Dustin James Ashley) who works at the same depressing doll factory. They converse, of course, and share fast food lunches on the job, but there’s absolutely nothing holding them together except for a want of something else to do. She likes to give him rides, and feel important, and he’s so passive that it’s possible he spends time with her because it keeps him from disappearing completely. She’s a shy, reserved, wholly uninteresting woman, but this job and this life are all she has, and despite the cruel routine, one can imagine that she’d prefer it to the unpredictability of a more interesting life course.

More than likely, she has waited all these years just to arrive at the point where she can perform a dehumanizing job without thinking, if only because she’d rather be secure than stimulated. Nothing changes, nor should it, and yet, it’s our common lot, not simply Martha’s story. I think about it often, but this film convinced me that human beings — despite their lip service to adventure and “spontaneity” — want every single day to be exactly the same. What, after all, is the goal of every hard-working drone, but relaxation and retirement? To think that we postpone the pleasure and possibility of youth so that we can shuffle through their shattered remains when we are least likely to enjoy them is the surest sign yet that we’ll make any sacrifice to arrive at absolute stasis.

Into the mix arrives young Rose (Misty Dawn Wilkins), a sexy (and scheming) newcomer who eyes Kyle, if only because he’s relatively sentient. We soon learn that she is selfish and unnervingly hostile, but she masks her needs with a sweet demeanor and soothing voice. And hey, she’s not middle-aged and overweight. In another movie altogether, Kyle and Rose would embark on a passionate, forbidden affair, but instead, their lone “date” is little more than two creatures hanging around each other to keep from falling asleep. They have nothing to say to each other, no real concerns to share, and yet neither seems troubled by this decided lack of chemistry.

Within days of seeing this movie, I watched a couple at a restaurant share a meal, but remain completely disengaged from each other. They neither spoke nor shared eye contact, and this lack spoke volumes about how we usually share physical space, but only out of habit, rather than a coherent, definable explanation. When pressed, I’m sure quite a few of us would have no idea why we are in a particular relationship, or claim to be in love, but we go through the motions anyway because we’re too exhausted to do otherwise. Our current state might be pushing us to the brink, but as rats in a maze, we fall back on the devil we know.

Needless to say, Martha is outraged by Rose’s interference (how dare she date a young man she, well, doesn’t and wouldn’t date), although you’d be hard-pressed to know it. We understand what has taken place, but the actors (non-professionals, all) are too wise about real life to make overt, melodramatic gestures. Yes, we can often fly off the handle, but most of the time, we internalize our rage, disappointment, and disgust, and simply mutter “fine” when asked how we are at any given point in the day. To do otherwise would be to invite conversation, and we’re far too inarticulate to express emotions that seem so far out of our control. In a sense, that’s all Bubble appears to be — a small, narrow world where people work, eat, and lounge around, and the only real drama in years occurs when the new girl takes a bath while housecleaning.

These are people alienated from a larger context; for whom social issues, politics, or philosophy are “out there”, acting as larger forces beyond their control. And as they have no real power, it becomes necessary to fasten tight to that which does make sense — the soul-crushing lack of a pickle on one’s hamburger, or why the infernal microwave doesn’t work in the break room. Why else would these trivialities provoke such blood-filled rage unless, even subconsciously, they masked a deeper despair that has no real solution? One can throw a wrapper back in the face of a zit-faced restaurant employee, but where do I go to repair my broken dreams? If I’ve wasted my life, what line ensures that I won’t have to face the mirror?

Bubble also involves a murder, and its brief investigation, and its eventual resolution, but unlike most Hollywood formula pictures, it’s less about what happens than why. Even then, we don’t really have the smoking gun of a clear motive. At bottom, we understand that violence is rarely planned or discussed; it often results from impulses we never knew we had, that is until they rage forth at the expense of another. And let me say this — there’s an interrogation scene late in the film that is so authentic and low-key that it becomes the standard for the future of cinema. It’s so clean, and subtle, and real, that I couldn’t imagine the procedure ever going a different way again.

When so many films use hot lights and pounding scores, Bubble prefers to let small words become larger indictments, even if we have to do a double-take to make sure we got it all. And when we find out “whodunit”, it’s not so much the end of the road as a further insight into the quiet corners of these all-too-typical lives. After all, fiction may be about lashing out with grand schemes and elaborate plots, but reality is no more than possessiveness, jealousy, fear, and pettiness. When we’re hurt, we kill. Why, then, pretend we all have a bank heist in our bones?

As said, these are non-actors, and Soderbergh (and the screenwriter) asked that each person help construct his or her own dialogue. This partnership of creation can often lead to disaster (I’ve seen far too many “independent” productions that are one step up from a high school play), but here, it helps the film dance along the edge of a documentary. As no one is performing, at least in the conventional sense, an almost unbearable tension arises from what should put us to sleep. And almost without even trying, Bubble tackles a subject almost non-existent in our creatively bankrupt age: rage, American style.

They say that tough times produce great art, but the era of Bush II has largely been about obsessively evading truth, from the screen as well as the page. The late burst of political films in 2005 (Syriana, The Constant Gardener) helped bring us around a bit, though we’ve yet to fully embrace the unadulterated anger that is our due in these times. Bubble is far from a polemic, but it does look under the covers at where we’re going; how so many lives — unfulfilled, suffocating, and painfully sad — let us know with a driving beat that we’re not really in this thing together, and one’s fellow man is nothing more than something in the way.