I have nothing against Steven Spielberg as an entertainer. Like the master of ceremonies at a three-ring circus, he is not above resorting to every method at his disposal in order to shock, astound, and thrill his audience. Amazingly, he seems to know exactly what the public wants at any given moment, even though times and moviegoers change. As such, he is the “people’s filmmaker” – a populist champion of the silver screen who believes that in order to reach the widest possible audience, those “people out there in the dark” must always feel as if they and they alone are being spoken to, albeit in a language everyone can understand. Spielberg would, therefore, never talk above his audience, nor would he give them more than they could handle. And, if this means that emotional cues, oversimplification, and uncomplicated motivations are required, so be it. Spielberg, despite his gifts as an old-fashioned storyteller, would never risk his status as America’s favorite director, perhaps one of the few the average hillbilly in the street would even recognize.

So, there we have it: Spielberg is putting on a good show. But is he an artist? I have never thought so, and my feelings are as steadfast as ever in the wake of his latest crowd-pleaser, Catch Me if You Can. Some might argue that after the “difficult” shoots of A.I. and Minority Report, Steven is entitled to take it easy and coast for a bit. True, his previous two efforts were darker than usual, but there remained a sugar coating in each that cannot be denied; an insistence on closure and redemption that Spielberg would not avoid at the risk of his life and reputation. This speaks to the most glaring weakness of Spielberg’s canon – the world can be bleak for a time, but he simply cannot carry through on such thoughts to their logical conclusion. Even if an ending feels (and is) tacked on, shoehorned, or unnecessarily added to keep nihilism at bay, Spielberg is more than willing to sacrifice art and narrative consistency in favor of phony uplift.

If Spielberg fails to elicit a toothy grin or at least a smile after the tears have been wiped away, he would fade away into the hills by whence he came; another “eccentric artist” who scrapes and saves in order to make that one great “statement.” Yet, as we know, Steven is at least as rich as a Saudi sultan, so it is obvious that the smiles continue to arrive without delay. You might insist that before Catch Me if You Can, his “experiments” were box office failures by Spielberg’s gargantuan proportions, but it is undeniable that had those films contained conclusions as bleak as the scripts demanded, they would not have been made at all.

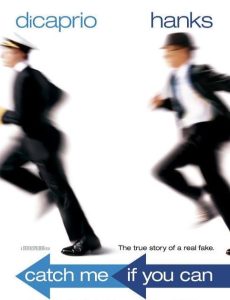

What, you might be asking, have I to say about Catch Me if You Can? Based on a true story (which, in Hollywood-speak, means an accuracy rate of about 10%), the story concerns the life and times (or at least a few years) of con-man extraordinaire Frank Abagnale Jr., played with gusto and pluck by Leonardo DiCaprio. Confused and saddened by the impending divorce of his parents, Frank takes to the streets in an attempt to fool as many people as possible. He “becomes” a Pan Am pilot, cashes millions of dollars in phony checks, passes himself off as a doctor, and tries his hand at the law, all the while evading the detection of obsessed gumshoe Carl Hanratty (Tom Hanks). Throughout the films’ 140 minutes (which is overlong by at least 20 minutes), we watch as Frank moves from one con to the next, seemingly all for the thrill of it, rather than any financial reward. We realize at once that the cons, while based on fact, are obviously exaggerated and fictionalized, for even in an era before computers, I doubt that Americans were this easily fooled. Okay, maybe it’s possible, but not in the manner portrayed. If it were this simple, one wonders why the entire population wasn’t of the criminal class.

Perhaps Spielberg is making a statement about how we believe what we want to believe about people based on rank and uniform (and how we are awed into stupefied silence by someone who at least pretends to know what he is talking about), but I doubt it. This is no philosophical treatise, but a mindless romp through 1960s American life. Entertaining? Yes, up to a point, but Spielberg is doing nothing more than recreating a time and place (“Ooooh, look at those crazy Pan Am uniforms!”). He does it well, but his only intention is to send the audience on a whirlwind; pushing them along without any pause for reflection or contemplation. Am I insisting that all films have such a goal? What is so wrong with a wild ride without apology? Nothing, in theory, but I must admit resenting the success of Spielberg, who does this shit so effortlessly.

The film glides and swoops; crafted so well that I had to wonder if it all wasn’t done by computer (Spielberg enters his usual data and lets it all run). Perhaps I simply want Spielberg to break a sweat on occasion; to earn our entertainment dollar rather than taking it for granted. Yes, yes, Steven, I am charmed by the flash and color. I am hooked by the music and the near-misses (“Will he get away with this one?”) But I have a problem with any film that will elicit the same reaction from each and every patron, whether that person is a grandmother or a pimply teenager. Mass appeal doesn’t do anything for me other than send me even deeper into my alienated, isolated cave where films can (and must) be interpreted, analyzed, discussed, and if need be, fought over with crude weapons. I want conflict and blood, not a collective nodding of the head that says yes, all was good and yes, I was entertained.

Again, the film is far from a disaster, and I can even admit to liking it from time to time. The performances were sound (although the Oscar buzz is a bit much), the transitions crisp and clear, and the period detail spot-on. Still, I cannot help but feel a void after watching it; like I had just had my first sip of forbidden alcohol and wondered, “Is this all there is?” The film satisfied on only the most basic levels and because I was not challenged, it will fade from memory and take a place beside all the other forgettable slabs of celluloid that dominates the life of a film buff.

But what of the feeding frenzy surrounding the film’s release? Why the almost universal gushing? I must assume that even critics, as wonderfully elitist as they can be, have a secret yearning for well-crafted trash. Even they, it seems, tire of speaking only to the lone man in the back of the room. Just once a year, they cry, let us have a word with the philistines up front.