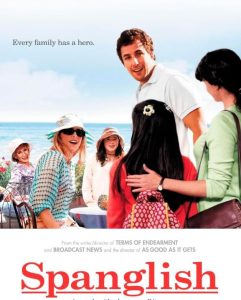

Written and Directed by James L. Brooks

Starring:

– Adam Sandler as John Clasky

– Tea’ Leoni as Deborah Clasky

– Paz Vega as Flor

– Cloris Leachman as Evelyn

Matt Cale hates the kids…

“My brain is evaporating,” a character utters near the end of Spanglish — James L. Brooks’ latest effort to convince us that everyday people are wiser, saner, and more articulate than everyone else — a sentiment that nailed exactly what I was thinking at that point in time. It’s always a sign of trouble when Adam Sandler is the voice of reason in any film, although he was so pathetic that I’m not sure he was meant to be sympathetic. It’s a film about family, the ties that bind, and all that crap, which might have had appeal if it knew where in the hell it was going. I was frustrated, pissed, distracted, and disengaged, but more importantly, had no idea if there was a fucking point to all this screaming, crying, and milling about.

Normally, I would applaud any effort to wander around without any concern for resolution or redemption, but that’s not what Brooks has in mind. There’s closure all right, and a moral lesson, and all the hugs and kisses that come from goodbyes, only nothing that points in the direction of me giving a shit. There is a clear, unambiguous narrative, so it’s not as if misinterpretation were possible, but I can’t argue that what I saw featured anything other than actors hitting their marks, reciting their lines, and standing tall, puffing out their chests, and hoping that Oscar pays attention. Knowing Brooks’ career, that is all-too-likely. Hell, if someone like Helen Hunt can win one of the bloody things under Jimmy’s steady hand, why not Sandler?

The title refers to the clash of cultures that Brooks seeks to explore, which means, if we are dealing with the United States and Mexico, it will involve a wealthy white family and a Mexican woman serving as their maid. The maid in question, Flor (Paz Vega, who is a dead ringer for Penelope Cruz), comes across the border (legally, I think) with her daughter, sets up shop in California, and is eventually hired by Deborah Clasky (Tea Leoni). Deborah is a typical Hollywood creation, or more accurately, a typical Brooks woman — white, neurotic, and prone to teary outbursts. Her husband, John (Sandler), is a world-class chef, who just happens to own his own restaurant.

They have two children, only one of whom is given any real dialogue (the daughter, Bernice), and she, predictably, has issues with her nutty mother. You see, Bernice doesn’t meet the expectations of her fitness freak mom, and is having trouble in school. As a result, she is criticized, teased, and ignored when necessary. There’s a lot that goes unspoken between the two, which is just as well, for if I know Brooks, he’d manage to throw out every parent-child cliché, only dressed up with the sort of poetry that no one outside a movie set could ever conjure up. And then we have Cloris Leachman as Evelyn, Deb’s mother, who is a former jazz singer now reduced to a pathetic booze hound, but also insightful as all get out when she needs to be. Needless to say, her gallons of wine and mixed drinks will disappear at just the right time in the plot, allowing her to help her daughter through a particularly boring crisis.

The story, then, involves Deborah’s attachment to Flor’s daughter, her insecurity leading to infidelity, and a growing attraction between John and Flor. There’s more, of course, but do you really care? Deb even arranges for Flor’s daughter to receive a scholarship from a ritzy private academy, which is initially resisted by Flor because, well, there’s that pride thing and the subconscious desire to keep her child in poverty lest she realize that there is more to life than cleaning gringo toilets. Flor, despite her beauty (yeah, all maids look like they just stepped from the pages of Vogue), is a repellant creep of a character, for she makes every decision out of ethnocentric cultural attachment, even if she’s hurting her daughter in the process.

This might have been acceptable had she been punished for it (as in the far superior Real Women Have Curves, where the daughter left for school in New York without her mother’s approval), but the film’s closing shot — and dialogue — endorses the idea that preserving family trumps the fulfillment of one’s dreams. “I am my mother’s daughter,” the voiceover states, which, in this context, only means that she will not go to a fine school or land a good job because staying poor is more authentically Mexican. Ah, but she might be on to bigger and better things, as the entire film is presented as a flashback, where the girl is telling this tale as part of her application to Princeton. And what was that scene like, I wonder, where she revealed that an elite East Coast school beckoned? Apparently the mother retreated from her stubborn ways, but how are we to imagine such a reversal after the implications of the closing shot?

And yes, I did say Adam Sandler made an appearance. He’s not the central focus this time around (which is good), although he’s not really credible as a run-down milquetoast. Playing the most forgiving husband in cinema history (read: emasculated pussy), he achieves a subtlety that is far more appealing than the screeching man-child he usually plays, but I hated his ass just the same. He falls in love with Flor for no apparent reason (she can’t speak English until the second half of the film), although one suspects it’s her sizzling Latin beauty. After all, I doubt he’d be all tongue-tied with Lupe Ontiveros scrubbing his shorts. It’s clear that John needs a sympathetic ear these days, what with a psychopathic wife to deal with, but even that hunger to connect doesn’t make their “big bonding scene” on the beach any less tiresome. He says something “wise” about worrying about your kids, and what’s important, but as he utters this New Agey crap, we remember that earlier, he seemed to reject the idea that a four-star review for his restaurant was a big deal. Despite the fact that the notice made his eatery the top spot in the LA area (the place is booked for months), he is plagued by sorrow and pain.

And it is here where Brooks is bringing us the bias of the Hollywood screenplay — look not to one’s gifts or talents for fulfillment; seek only the wide eyes of your children. A job is just work, even if that same “irrelevance” ensures those same brats a great education, all the latest trinkets, and a stability impossible in some shithole like Mexico City [Ed Note: Matt Cale obviously has never been to Mexico City]. But somehow Flor is the better parent in this twisted universe, even though her talents extend no further than being able to get grape juice out of an expensive rug. But she loves her daughter (I guess), and that’s enough these days.

Funny, but I’d rather have Harold Bloom as a father and have him ignore me for weeks at a time than some illiterate lunkhead who played catch with me every evening. Is it possible that a kid could be inspired by, and look up to, a parent who works his or her ass off? Or who might be passionate about something other than dirty diapers and t-ball games? Why must everything that lead to a paycheck be so demonized? In the end, these people mean nothing to me. Whether or not she gets into Princeton is just another minor detail; something to fill the time and meet with my crushing indifference.

Special Ruthless Ratings:

- Number of times I thought that Sandler should stick with his bread and butter: 8

- Number of times this seemed ironic given that you hate the “old” Sandler: 4

- Number of times you responded, “Yes, but at least he knew his place”: 4

- Number of times you also added, “And you’re no Jim Carrey”: 3

- Number of James L. Brooks movies I’ve now seen: 4

- Number of times I’ve been disappointed: 4

- How often I have to remind myself that this guy helped create The Simpsons: every waking second