It would be most accurate to describe Anthony Minghella’s Cold Mountain as a film of the Civil War, rather than about the Civil War. It uses America’s greatest conflict as a backdrop, complete with period costume, accents, and overall flavor, but at no time do we believe that we are to be assessing political arguments or discussing the evils of slavery. We do get a masterfully staged battle sequence (Petersburg, and the legendary “Crater”) and Blue and Gray are prominently displayed, but the ideas of that era are conspicuously absent, almost as if the filmmaker were trying desperately to avoid alienating members of the audience. Of course, it would be silly to state the obvious (slavery was morally wrong) and just as silly to oversimplify the situation (that slavery was the only cause of war), but to leave the issue out entirely (reducing it to the frustratingly vague term, “the cause”) is irresponsible and does take away from the experience.

But again, I was not expecting, nor was I desiring, a film about right and wrong, or good and evil. But I was expecting the implications of the war (including treason, emerging industrialism, even the phony “states’ rights” mantra of the South) to at least hang around a bit, rather than take an immediate exit. What we are left with, then, is a visually spectacular, ho-hum romance that works on its own terms, but cannot be called a triumph. There is simply not enough on screen to justify my approval.

Because the film is so lush and horrific at the same time (as said, the Petersburg sequence was one of the best scenes of carnage I have seen in quite some time), I was captured from the outset, although my attention wavered whenever the romance took center stage. I have no doubt that the desperation of the time fostered such “quickie” relationships (with death an ever-present reality, there was little time for courtship), but for a film, it weakens our empathy because we cannot understand why a woman would long for a man with whom little was exchanged except for a brief kiss. They discussed nothing, revealed nothing, and are as much strangers as they would be had they existed on different planets.

But then I realize that our notion of romantic love is exceedingly modern, and few couples of that time had such chats in the course of their lives. As farming was the primary way to make a living, children were needed immediately to help with chores, and as long as a potential mate was reasonably healthy and breathing, he or she would do as a partner. Still, as I didn’t know a thing about these two people before or after the bloody conflict that separated them, I found it hard to care whether or not they reunited. I am sure the incurably romantic among us will swoon nonetheless, but for me, love must always involve a meeting of the minds — a period of unshakable connection — before it can be so openly declared.

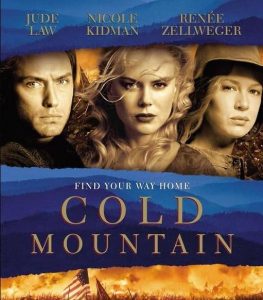

The couple in question, Ada (Nicole Kidman) and Inman (Jude Law) are the least interesting characters on screen, but there are sufficient distractions in the midst of their plight. The other main character, Ruby (Rene Zellweger) is a local bumpkin who appears on Ada’s doorstep to help save her farm after Ada’s father (played by Donald Sutherland) drops dead early in the film. A script weakness here: we know Sutherland is doomed because early on, he registers a troubling cough. And as we know, no character who coughs in the first act is alive by the third.

So, Ruby the mountain woman (she’s so tough she tears the head off a rooster) begins a friendship with courtly Ada, and the two grow quite attached despite the difference in social rank. I will admit that Ruby is one of the few characters who feels alive, although I would nod in agreement with anyone who blasted Zellweger’s hammy effort as an obvious bid for Oscar. From her proud strut to her determination to spend every waking second a-fightin’, a-cussin’, and a-stompin’, Ruby is a tornado of character. And given its showy nature, it will no doubt win the award. Still, I was strangely fond of Ruby, if only because she possessed a grit and fire that Ada and Inman lacked.

Inman deserts the army (he claims to no longer believe in the cause, but that is poorly established; in my mind he leaves to get a taste of Ada’s coochie) and begins a long journey home to see his beloved. Along the way, he meets a sinful preacher (played by Philip Seymour Hoffman) who is clearly the film’s comic relief, although he too has a spirit that I mostly enjoyed. He is a hypocrite, a liar, and quite the randy gentleman. At the very least he is a symbol of a failing religion that made me smile. They bond quickly, but are torn apart after being fooled by a smirking hillbilly (Giovanni Ribisi, overacting as usual) and his cabin of flirtatious women (sirens).

The pair are taken in by the “family” and while Inman remains true to his distant love, the preacher heads to the barn with several of the women. Of course, this is nothing more than a trap, and the two are quickly apprehended by a band of bounty hunters who have sworn to capture all deserters. Taken in chains, the pair is eventually caught up in a gun battle with Union troops, and only Inman survives.

Inman is then rescued by a goat-loving mountain mama, who tends to his wounds and feeds him fried goat meat. The point of these scenes, I believe, is to show that most people (average folks, y’understand) are untouched by war in that killing one’s fellow man is something those people in far off Washington concern themselves with, while “the people” continue to work, raise children, and tend the fields. It’s a romantic notion, but does little to contradict the notion that Cold Mountain is stubbornly apolitical. Inman’s Homeric journey allows us to witness stunning vistas, but I found myself hoping he would remain lost as any reunion would entail embracing a dull woman. I’d rather he romance the goat lady. Inman also meets up with a lonely widow (Natalie Portman), which allows for scenes of quiet power, although I suspect were included only to balance the scales of brutality. Here, Union men are callous and hard, which is necessary lest the film be criticized as one-sided. True, Union and Confederate soldiers alike committed atrocities throughout the four years of war, but I resented the tit-for-tat approach.

The remainder of the film involves Ada and her new “family” (Ruby is reunited with her estranged father) trying to evade the bounty hunters. Eventually, Inman returns to Ada and surprisingly, the scene wasn’t nearly as moving as it should have been. The first order of business is to hit the sheets, which reveals two naked forms that are insanely well preserved considering the ravages of war, disease, and starvation. Perhaps salt-pork is better than we imagined. But, given that this is a tragedy, the love affair is brief indeed, and Inman is lost forever in a scene that does little but demonstrate that even a director of Minghella’s stature is not beneath the Talking Killer cliché. Inman’s death fulfills Ada’s vision in the well (films set in the past always have some kooky local legend that ends up having validity), and she is left alone once again. We might cry, but I remember the thousands of corpses that earlier littered that Virginia battlefield and frankly, I’d rather weep for them (at least the ones wearing Blue).

The ending (set years later) is all about closure (American epics share this annoying trait), where we see Ada and her grown daughter, along with Ruby and her new family, as well as her father (still alive after being shot at least a hundred times). Another note: why is it that whenever characters have sex, a pregnancy always results? I mean, Ada and Inman screwed only once! Given the high infant mortality of the period and that a woman’s window for fertilization is rather brief, isn’t it a bit much to expect that one night of sex produced a healthy, happy child? Maybe not.

Maybe I’m busy nitpicking. Still, I view such a development as a sop to the romantics among us; an attempt to give these characters everything they desired, in spite of it all. But can we imagine Ada and her makeshift family as a true success story? What about the terrible years of Reconstruction? What of the war dead and assassination of Lincoln? What about the Radical Republicans and starting the world anew? Yes, it all makes sense to me now. Given that we were denied the horrors of war except for its impact on a few little people in North Carolina, it stands to reason that these same people would have no idea of, or concern for, the political upheavals in distant towns. They lived through the war ignoring politics, civil rights, voting rights, slavery, and economic revolution, so why not live the post-war period in exactly the same way?

Okay, I am critical, and yes, I believe Cold Mountain is flawed. Still, the film is a nice way to spend the afternoon and it would be a mistake to avoid it. I would not place it among the best films of the year, nor would I rush out and see it again, but I would say that despite its less than admirable turns, it is a film that warrants discussion, at the very least for what it omits. Ada and Inman might be an unfortunate pair to highlight in a film of this length, but the supporting players more than pick up the slack in that they gave me something to turn to when the dullards refuse to get out of the way.