I don’t think it is too much of a broad generalization to proclaim that most people will find Uzak (Distant) hard to watch. It is essentially a silent film with less dialogue than even Rambo III. Moreover, the shots linger for sometimes more than two minutes, often without any characters on screen at all. Maybe there is a boat floating in the harbor, or maybe a character walked into a room, and the camera is just showing us the hallway. With this movie, patience is a virtue, for the payoff is worth the stretch. Like the great Kitchen Stories, I grabbed this film using the same on-a-whim metric of “Man, my country sucks; hey, this is foreign.”

Once again I was rewarded. For those of you with attention spans longer than five seconds, there is much to marvel at over Nuri Ceylan’s latest film. Uzak is also not–for lack of a better term–“arty.” In other words, there is no pretension, no unnecessary idealization and frankly no really “important” ideas being expressed. Not to say that the film is empty-headed or shallow, or not artistic, no. It is a quite moving, disturbing and ultimately powerful piece of filmmaking. For, as Herzog talked about in Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe, and I’m paraphrasing, “we’ve learned that film does not inspire revolutions. What it does do is inspire,” than Uzak has inspired at least one viewer (me). To find out exactly how and why, read on.

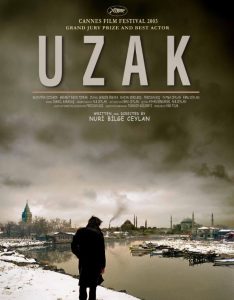

Set in contemporary Istanbul, Uzak actually opens in a what to my eyes looks like an idealic mountain Hamlet. We meet Yusef, who looks like somebody cut off one of Lemmy’s moles and pasted it onto the side of a young Manuel Noriega’s head. Though not a line of dialogue (save for an answering machine message) is muttered during the first eleven minutes of the film, we learn that the factory in Yusef’s town has shut down and since there are no other job prospects, he sets off to the big city in order to secure work on an ocean freighter. The opening shot also sets the tone for the rest of the film, for it takes Yusef a full minute to walk across a snowy meadow to the road and he keeps on walking out of the camera.

Slowly the camera turns to show the length of the road and the isolation of his town. When a car finally approaches, Yusef walks back into the frame to thumb for a ride (actually, and apparently, in Turkey, you flag down a passing motorist by waving your hand, palm down). We next meet Mahmut, a fairly successful photographer, whose ambitions in life seem to only be smoking, watching TV in his big red chair or getting a glass of wine at a local bar. Oh, he also really wants to kill the mouse that lives in his kitchen. He lives alone in a large upscale apartment, refuses to call his mother and just generally looks beat. Not unhappy, mind you, just detached.

Yusek and Mahmut are from the same small town and Mahmut agrees to let Yusef stay with him until he finds work on a ship. While by no means an ogre, Mahmut is petty and spends much of his time putting Yusef’s shoes in a cupboard and turning off any lights his guest may have left on. Yusef, for his part, is aimless. He tries initially to find work, but as there isn’t any, resigns himself to wandering around town, creepily following women. At one point it seems as if maybe Yusef found a job, but when he indirectly asks Mahmut to be his “guarantor,” the latter doesn’t even notice. Honestly, Mahmut is just oblivious to Yusef’s predicament.

Another thought I had was that Mahmut wants Yusef around, for some reason. I say for some reason, because Mahmut not only doesn’t talk to his guest, but seems constantly annoyed by everything Yusef does. There is a particularly nice sequence where the two are watching television in silence. After a few minutes (I’m not kidding–Ceylan actually has them watch TV for a few minutes) Yusef gets up to go to bed. Once his door is shut, Mahmut pops in a porno which he watches for another minute or so until Yusef emerges from his room, looking for a magazine. Mahmut of course changes channels and pretends he is just surfing around. Yusef starts watching again and Mahmut turns off the TV announcing that it is time for bed. Yusef goes first and when Mahmut is on his way, he find’s his guest’s shoes and angrily throws them into the cupboard and kicks it closed.

Things deteriorate for Yusef, as his mother cannot get her rotten tooth pulled for she has no money and he has not earned any to send her. Moreover, his habit of following women around town goes from just plain creepy to scary. There is one scene in particular on a bus when Yusef has his legs spread wide open and his knee is touching an attractive woman’s leg. He is leering at her. It was just gross to watch; quite upsetting. Worse–from his point of view–is that he just cannot find any work and he starts to get on Mahmut’s nerves. Mahmut screams at him, explaining how useless of a guest he is and how he himself had come to Istanbul without a cent and through hard work has become a success, etc.

Yusef, who we now see clearly as a man-child, tries his best to defend himself, but, in the end, there is no excuse for his disrespect and sloth. We learn that other aspects of Mahmut’s life are crumbling; his ex-wife is moving to Canada with her new husband and they quite obviously still have feelings–unresolved or not–for each other. Worse, his mother is sick and dying. In a very real sense, it doesn’t occur to Mahmut until, well, until it is too late, that Yusef is all he has in the world. Mahmut is certainly all Yusef has.

In the end, and through the best use of a dream sequence to date, the soul-crushing loneliness that is life is brought home with a bullet. The theme of Uzak is actually one of my very favorites and has best been explored by Rob Wright in the NoMeansNo song, “The River.” Essentially, Wright acknowledges that sure, we’re all floating together down the same river of life, but we are drowning separately as individuals. Resistance is just a waste of fucking time, as Wright sings, “I would save you; give my life but it’s already–SACRIFICED! To the river…” To reiterate, even in such an obvious situation–one man has no means, the other has no one–two men left alone get it all wrong.

Mahmut could have put Yusef to work as his assistant, easily. Yusef could have vouched for Yusef so he could get a job. Mahmut could have said what he needed to say to his wife. On the other side of that coin, Yusef could have tried harder to find work, he could have obeyed Mahmut’s rules, he could have just simply said hello to the beautiful redhead in the stairway. But, no. For both of them. Just plain no. They are fully human and therefore fully flawed, incapable of softness, kindness or empathy for the Other, until it is just too damn late. Uzak isn’t so much a tragedy as it is a giant mirror, showing us just how sad, doomed and yes, distant, we really are. Aside from all the above, this sucker is beautiful. I highly recommend you check out this haunting film.