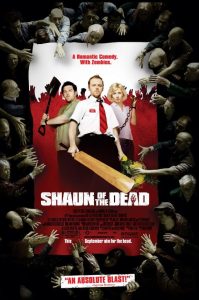

I have come to the conclusion that it is impossible to make a bad zombie movie. Even if they aren’t exactly true to the Romero spirit with tongues planted a bit too firmly in cheek, the very essence of the genre — the delightful spirit of slaughter and chaos — keeps the magic blissfully alive. And even if Edgar Wright’s Shaun of the Dead doesn’t reach the classic heights of Big George’s trilogy, it manages an evening’s entertainment that is genuinely satisfying, without apology.

For while it is great fun to watch the blood splatter, the brains ooze, and the limbs crack and tear, Wright’s film manages a sly wink now and again, as well as a bit of social commentary to chew on with the small intestine. This would be easy to miss as the film’s style is frantic and absurd (whooshing cameras and the like), but it is there for those seeking it out, although one can be forgiven for insisting on being as brainless as the undead for a few hours while the party on screen moves forward. I found it best to pursue both angles, and as a result I found a movie that can be heartily recommended, even to those who never thought they’d enjoy glassy-eyed cannibals stumbling around London.

The two main characters — Shaun (Simon Pegg) and Ed (Nick Frost) — are a delightful pair for many reasons, not the least of which is their insistence on dry, predictable routine even in the midst of Armageddon. And it is here that I found the most joy, that is until a teeming crowd of zombies performed a characteristic evisceration of an asshole who just might have been a stand-in for Harry Potter. The film begins with Shaun’s pitiful life: a dull job, a dimwitted roommate, and a girlfriend who quite reasonably insists on going somewhere beside the local pub after work.

She’d like a little spontaneity from Shaun, but he is so lacking in imagination that he’d piss it all away to remain unchallenged and comfortable. And just like every other day, Ed wastes away with his video games, doesn’t clean the house, and refuses to leave his seat to answer the phone. We can imagine that prior to meeting these young men, each and every day played the same, almost as if they were trapped in a cruel loop of their own creation. And when Shaun wakes up, visits the corner store for a soda, and returns, he’s so locked in place that he fails to notice bloody handprints on the store’s cooler, as well as the dozens of zombies wandering the streets. Just another day in the British Empire apparently, and certainly just another day in Shaun’s uninspiring existence.

It speaks volumes that Shaun and Ed don’t really notice anything amiss until they hear it on television. Even a visit by a zombie is attributed to what they believe is the chick’s drunken state, until of course she rises up after being impaled on a pole. Perhaps it is an obvious connection that modern life has so stripped us of our humanity that zombies are a seamless substitute (if anyone would actually notice, that is), but the sense of play Wright insists upon undermines any effort to challenge the film’s originality.

These zombies are us, as Romero also believed, but Wright isn’t about to force his point. As I said, it is the adherence to routine that damns these folks, and after the zombie holocaust hits its stride, the group (Ed and Shaun are joined by three friends, as well as Shaun’s mother and stepfather) seeks shelter in — where else? — the familiar neighborhood Winchester pub. Even as the undead are crashing through windows, Ed insists on playing the same video game as when we first met him, as if the end of the world wasn’t a sufficient reason to give up simple pleasures. And when the pub’s power doesn’t come on, it is enough that they get the TV to work, as if the shrill banter of a talk show host is enough to keep the flesh-eaters at bay.

Eventually, those who have been left alive begin to succumb to the bites they have received, and before long only two remain. A small measure of sympathy is attempted (as when Shaun is forced to blow his mother’s head off), but we know that Wright is only momentarily bowing to conventions before proceeding with the massacre. For some reason known only to myself and my psychiatrist, I never tire of watching zombies get killed, even though the excitement would seem to be limited by the fact that only a head shot will stop them for good.

Maybe it’s my way of taking pleasure in humanity’s extinction without actually having to root for outright mass murder (that I’ll leave to my interior monologues). I mean, these are “only” zombies after all, so it’s acceptable to cheer their dismemberment. One such scene that had me in tears occurred in the Winchester; when the pub owner, now a member of the walking dead, attacks the group. As a Queen record spins on the jukebox (surprisingly not “Another One Bites the Dust”), the old man is battered like a cheap pinata. Despite receiving one of the most savage beatings ever recorded, he simply refuses to go down. You gotta admire the toughness of the old coot, even if he is no longer alive.

In the end, our hero gets the girl and, presumably, a new life. But how “new” could it be given that he lives in the same flat, more than likely has the same job, and can’t see fit to part with Ed, even though he’s now a zombie who lives in the shed? But even Ed is better off, for he can play the same video games with Shaun and won’t ever be lectured for failing to vacuum the living room (he has to remain handcuffed, after all). As with the Romero films, we never really learn the source of the zombie plague, and to be honest, it doesn’t matter one bit. They’re here (haven’t they always been?), and we’ll have to learn to adjust. Shaun of the Dead is nothing more than this premise — zombies arrive, walk around a bit, and feed generously — and the story itself is cheerfully paper thin.

What else can be done but watch as these characters run around trying to find shelter? And yet it’s more than enough. Of course, a generous helping of British cheek doesn’t hurt either. In the end it’s a parody, but one overflowing with reverence, respect, and an insider’s knowledge of the genre. Nothing will ever equal 1978’s Dawn of the Dead for its vivid reconstruction of humanity’s last, pitiful gasp, but Shaun of the Dead has an argument all its own — that our end may not come in a flood of shattered corpses, but through our complacency and resistance to change. It’s not the teeth meeting flesh, then; it’s our refusal to get off the fucking couch that will do us in.