What do I need to say about a film that stars Gregory Peck, Walter Huston, Joseph Cotten, and Lillian Gish, and yet the most dignified performance is given by one Butterfly McQueen? Or where we are asked to believe that an overheated Jennifer Jones–ridiculously clad in a black wig and pounds of cheap bronzer–is not only a Mexican, but an alluring sexpot, who evidently seduces her men with a winning combination of wooden, melodramatic acting and eye-rolling detachment? Or consider the case of Lionel Barrymore as the Senator.

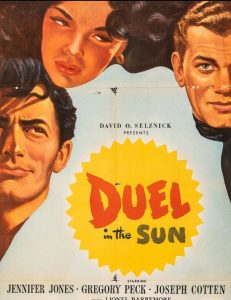

What are we to make of a supporting turn that manages to make his Mr. Potter from It’s a Wonderful Life seem like a deaf mute by comparison? David O. Selznick’s Duel in the Sun, his first pathetic attempt to recapture the magic and wonder of Gone With the Wind, is surely one of the most insipid epics ever made, yet I defy anyone to look away, as its histrionics make the average soap opera an exercise in subtlety. Shot in gorgeous Technicolor hues and using Western landscapes to their full effect, these actors sweat, groan, pant, and heave, all in service of an alleged story about the rise of the railroad.

Needless to say, there’s a love triangle, as Lewt (Peck) and Jesse (Cotten) both compete for the prized twat of one Pearl Chavez (Jones), a woman so low on society’s totem pole that she eagerly admits, “I’m trash, I tell ya–trash!” And so she is, which makes her even more of a catch, as there isn’t anything even remotely interesting about her other than the fact that the only other woman for 100 miles is some geriatric with a bad ticker. Lewt appears to have the upper hand as he’s mastered a few horse tricks, but he’s too eager and resorts to rape out of sheer impatience. Jesse eventually leaves the ranch after a disagreement with the Senator, only to return with his new bride in tow, although he admits that he still loves Pearl, only not in that way.

Lewt is the bastard of the piece, although he’s the only one who is even half alive, which he proves by taking off his shirt and demanding to see Pearl naked. True, the Senator snorts while locked in his wheelchair (just about the only intelligible words are some racist cracks about Pearl’s “half-breed” status), but we know he’s just a temporary reprieve from the real action. Pearl can’t really decide if she loves Lewt, so she marries the good-natured Sam instead, only to watch him gunned down by a drunken Lewt. To help Pearl, there’s the fiery preacher named “The Sinkiller,” who bestows upon the nasty wench a medallion that is meant to drive her naughtiness away. Of course, the trinket is lost as Pearl is being pawed by a horny Lewt while both stand half-naked at the local swimming hole, aptly named “the sump,” which itself helped foster the film’s nickname “Hump in the Sump,” to go with the more popular “Lust in the Dust.”

Everything ends–as it must–on a sun-scorched rock, where Lewt and Pearl face off with pistols drawn. Each shoots the other, which leads to a final embrace that will stand the test of time as one of the most shockingly bad scenes in cinema history. As Lewt screams for Pearl to hurry up for one final kiss, Pearl crawls along the ground like a fevered rattlesnake, making sure that we stand face to face with the sweat pouring from her exploding bosom. They do manage to secure that last lip-lock, and die within seconds of each other, soon to be food for the vultures and crows that inhabit the area. As director King Vidor pulls out to survey the scene–from his perspective fraught with meaning and pathos–we are in stitches, unsure about what we’ve just seen, but knowing full well that it doesn’t mean a damn thing.

Still, one is left with the unshakable belief that as bad as it is, it will always be preferable to the bad cinema of today, primarily because in the golden age of cinema, crap always came with impressive credentials. Every single member of that legendary cast believed in what he or she was doing, and they were led by a heavyweight producer who risked great fortune to bring his vision to the screen. There was no irony, or winking self-consciousness about anything in Duel in the Sun–this was an attempt to make the Great American Story, a film of high purpose and bold strokes. It is the sort of monumental failure that isn’t made anymore, and to prove it, why else are we still talking about it sixty years later?

That it remains legendary camp is a testament to its no-holds-barred commitment to delivering sex and violence in near-fatal doses. Selznick didn’t want snickers, after all, but respect, gushing reviews, and numerous Oscars. And he nearly got them, as Jones was put up for Best Actress, which for me now stands as the worst performance ever nominated for such an honor. And yet, even now, I wish she had gotten the damn thing. Somehow, nothing could have been more fitting.