Let’s declare the obvious from the outset: this is not a film for cynics, realists, and grouches. However, for all those who believe that life is but a dream, or every hardship and tragedy can be met with fantasy and escape, Marc Forster’s Finding Neverland will be that perfect cup of tea to warm your heart during the doldrums of winter. It is sweet, light, and kind, and as such about as desirable as twenty-five plucky orphans intruding on one’s evening at the theater. Oh yes, said orphans do in fact appear late in the film; a last-minute sugar injection just in case the previous ninety minutes hadn’t made the point clearly enough. While claiming to be the story of J.M. Barrie and the creation of Peter Pan, the film instead reveals hidden layers of creepy man-boy love; where an adult male spends far too much time with the wee ones, keeping the world at bay with romping, frolicking, and, it is assumed, fondling and undercarriage inspection.

Barrie, who to some would be a charming, idealistic dreamer, is for me a dreadful bore. He’s the sort of man who, when faced with bankruptcy, disease, and house payments, would shoo away doctors and accountants alike in order to watch a squirrel hop and skip through the snow. And he’s most certainly the sort of man who would leave his wife waiting at home while tucking in another woman’s children for the night, while imagining them flying out the window in a burst of innocence. In others words, an insufferable asshole in need of a sustained beating.

I’ve never understood the appeal of Peter Pan, whether as a metaphor for childhood, or literally as a dopey fantasy involving Indians, pirates, crocodiles, and fairies. Yeah, yeah, innocence is a wonderful virtue, as it is better to fly around with pixies and flying boys in their underwear than grow the fuck up and deal with life’s misfortunes. At the very least, Finding Neverland avoids the predictable turn where we learn that Barrie’s love of play arrived after a sustained period of abuse and neglect, but one must wonder why this man sought to avoid maturity. In an early scene, Barrie scolds a young boy for suggesting that a dog might not pass muster as a dancing bear. “Just believe,” Barrie insists, which is the obnoxious rallying cry of all the world’s lunatics; for whom empirical data is a mere illusion at best, and often a distraction from the imagination.

Fine, our current obsession with math and science scores speaks to an abandonment of wonder (the arts, language, and yes, imagination), but there is a time and place for such things. To live every waking moment in a dream world is madness, dear ones, not an inspiring life-choice worthy of emulation. As such, Barrie was unwell and in need of deep, psychological probing. Rather than let him wander about the forest with young, nubile children, stick his ass in a sanitarium and find out why his marriage never was consummated.

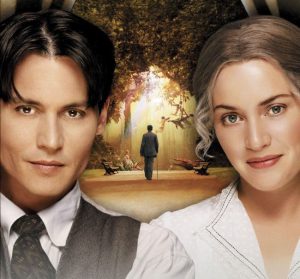

If we are to believe the film, Barrie wrote shabby plays for one Charles Frohman (Dustin Hoffman), the sort of character who is introduced, but never really explored in depth. We see that he is frustrated and mindful of the box office receipts, but that’s as far as it goes. After a particularly bad flop, Barrie, as nonplussed as ever, wanders into a London park and meets a group of well-spoken young men and their lovely mother. The woman in question, Sylvia Davies (Kate Winslet, always a pleasure), is doomed from the start, as she coughs in the first act. But she fights on, spending a great deal of time with Barrie, as he is inspired to write his immortal classic.

Barrie is especially fond of Peter (Freddie Highmore), a precocious lad who so desperately wants to come out of his shell. And so he will, although his big moment will be handed over to Barrie himself. During a party following the smashing opening night of the play, patrons surround the boy as they discover he is the actual Peter Pan. Right then, Peter shakes it off, saying that it is Barrie who is Peter, for it is his spirit that has brought this vision to the stage. Whatever. Perhaps the boy was reluctant to educate the crowd about the late-night sessions and naked romps in the lake that also helped develop the piece.

Barrie’s wife eventually leaves his ass, as expected, because they never had sex, a fact established here with one shot — each enters a separate bedroom. But we really should understand this bizarre marriage, if only to help explain the divorce. Was he impotent? Was he too busy with work? Or was he attracted to pre-teen flesh, while the marriage was a mere concession to Victorian expectations? Barrie’s relationship with Sylvia, while asexual, causes a scandal because she is recently widowed and he is, of course, a married man. And gay. The presence of Sylvia’s mother (Julie Christie) complicates matters, as she wants her daughter to get married and find a father for her children.

But Sylvia is captured by Barrie’s world, and it never enters the equation that he might fit the bill as a husband, or even a lover. Once again, why is this an unspoken fact for all involved? Sylvia’s tits are flowing, she’s attractive and refined, so why would Barrie rather dress up like an Indian and play with a wooden duck? And Christie’s appearance was depressing in the end, a reminder of how her retreat from cinema has been a tragic loss indeed. Still luminous at 63, Christie’s character is one of the few reasonable individuals in this mess, which means that she will be forced to come around in the end, applauding with great relish at a special performance of Peter Pan for the dying Sylvia. As always, rationality must be attacked, stripped, and converted to sappy emotionalism, lest the audience get confused about what’s important in life.

And of course (sigh), Sylvia dies magically, as she walks into Neverland at the performance in question, “taken away” to play with sweet children and fairies for all eternity, rather than die in pain and discomfort as she really would. And when Barrie comforts young Peter at the very end, his bullshit reaches epic proportions. Remember, this was a child who insisted that adults tell him the truth and who always seemed wiser than his years, and Barrie leaves him with the biggest lie of all — that he can always enter Neverland to visit his mother anytime he wishes.

Perhaps I’m a hard-ass and given to fits of rage and loathing, but I can’t think of a more improper way to deal with death. One need not get morbid or graphic, but the finality of death should always be communicated, especially to those who are just beginning life’s journey. Kids need hard facts and unvarnished truth, not illusion and phony stories to block out the pain. Just as we believe that kids will avoid sex so long as we dare not utter its name, we seem to accept that death and misery can be wished away, which is another way of saying “prayer.” Barrie, then, was no hero; but an irresponsible bastard who inflicted great harm on children while claiming to worship at the altar of innocence and love. You know, sort of like Michael Jackson.