One does not merely appreciate Akira Kurosawa; one is awed by him. His

status as the greatest filmmaker in the history of the cinema is beyond debate. Based on vision, diversity of subject matter, and consistency of greatness, he is an untouchable of such magnitude that one almost feels compelled to speak of him in hushed tones.

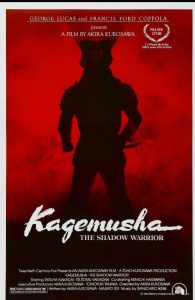

With 1980’s Kagemusha, his brilliance is reinforced yet again, despite his dismissing the work as mere “preparation” for the greater challenge of 1985’s. Perhaps he’s being modest, but to think that Kagemusha was but a trial run is to gain an insight into the mind of an artist that forces mere mortals to concede all further efforts in the act of

creation. If he’s capable of that, we argue, what’s the point of our pathetic scribblings? When someone like Kurosawa sees it all so clearly, we are forever running behind.

Kagemusha concerns the story of a thief (Tatsuya Nakadai) who is spared execution so he may act as a double (or “Shadow Warrior”) for the dying warlord Shingen Takeda (also played by Nakadai), but to reduce the film to a line or two is like saying Citizen Kane is simply about a guy and his sled. It’s not the plot that drives Kurosawa’s vision forward; it’s the scope of his humanity. As always, Kurosawa sees the human experience as a sad, desperate grasp for relevance and power, as we are burdened by the reality that in the end, historical forces out of our control sweep us along to our doom. The switch enables the clan to cling to life for a few remaining years (under the illusion of strength), but it is clear that they will soon be wiped out in favor of the next temporary regime.

As usual, Kurosawa lets us in gradually, through an examination of pained ritual and bursts of spontaneity that are invariably punished. And as we arrive at the shattering climax, we have been privileged to view things as a god; helpless to intervene and shamed by our passivity. Man and beast alike snort and wail, flailing about as if fully aware of the punishing indifference of the cosmos. We strive to stand and live on, but to what end? The disappearance of the rulers (dead? stolen away? a cowardly escape?) speaks further to this sense of abandonment, as if we are led to battle under a righteous banner, only to be humiliated for assuming there could ever be sufficient

cause to commit atrocities.

Visually, it goes without saying that Kurosawa has once again used color to saturate our minds with the splendor of horror. Each scene is so intricately designed and staged that we cannot conceive that a single filmmaker was able to pull it off. And yet, Kurosawa is the rare filmmaker who refuses to let an epic scope overwhelm his characters. And of course, his unparalleled battle sequences would be breathtakingly beautiful were they not in service of such colossal waste. But so much of what we admire is based on this crucial contradiction. We recoil as we embrace.