The fundamental problem with John Madden’s Proof is that mathematics is inherently — and inescapably — boring. Important, yes, and vital in order to understand our very universe, but impossible to curl up in front of a fireplace while a chill winter wind whips through the trees. On a deeper level, mathematicians are among the least interesting human beings alive, as their brilliance, so far beyond the layman, makes basic conversation an impossibility. I grant the math geeks of the world their superiority of intellect, but they’d be the last people I’d ever invite over for a cup of coffee.

And when we get into the realm of genius, as does this film, we are truly on dangerous ground, as only other geniuses could possibly relate to someone so gifted at a particular subject or idea. Moreover, a genius, usually focused exclusively on a single issue, is wholly incapable of living outside of that obsession. And when one considers the complexity and depth required to pour over advanced equations and theorems, it makes sense that these people cannot be bothered with everyday concerns. Their life is their work, and to attempt to introduce art, politics, cinema, philosophy, or history is to invade a sacred world that has erected barriers well in advance of one’s conscious confrontation with said gift. It is a life of the mind, and all else falls away.

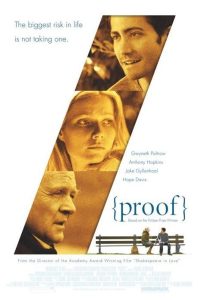

I admire the sheer cheek of David Auburn for attempting a dramatic work on patently un-dramatic material, but audacity is not always synonymous with success. Having seen (and been bored by) the play, I knew what I was getting into with the film version, but I went anyway because I knew it had the pedigree to receive numerous Oscar nominations, and I never miss a chance to blast the Academy’s idiocy and obvious preference for the mere appearance of importance. Starring Gwyneth Paltrow as Catherine, Anthony Hopkins as her father Robert, Jake Gyllenhaal as her friend Hal, and Hope Davis as her sister Claire, the film certainly has the chops to intimidate all critics into an embarrassed silence.

And while it is well-acted and earnestly performed, the tone is so self-satisfied and sad-sack that one cannot help but sigh with indifference. And for someone of Catherine’s brooding narcissism to be at the center of the maelstrom is so ill-conceived that I wonder what the play’s author could have been thinking. I can stomach unlikable and even insufferable, but at the same time, don’t ask me to care for them. Catherine’s crippling loneliness and fear regarding her own mental instability might matter to her, but they cannot possibly interest outsiders. She mopes, shuffles about, lets the dirty dishes pile up, and weeps like a wounded child, but at no point can we feel empathy for her plight. Catherine may in fact be turning into her father, a brilliant man felled by insanity, but in her case, the only disease I can ascertain is a violent, unparalleled self-absorption. Perhaps, dear, if you left the house once in a while or stopped staring at your own navel, your neuroses would be seen for what they really are. Wallowing in a sea of pain never cured anyone.

If there is a plot hook, it comes crashing at the end of the first act — did Catherine write this revolutionary mathematical proof that could change the world, or did she steal it from her late father and is now attempting to pass it off as her own work? Without knowing what that proof contains, it could easily be the sort of thing that might advance a struggling professor’s career, but has no further relevance beyond the ivory tower of academia. The proof’s importance, then, must be taken on faith, which is wildly unacceptable in this context. Because no one can relate to what is being discussed (and so little is even said to begin with), it becomes a parlor game of “did she or didn’t she” that sparks absolutely no interest for the audience. We’d root for her — hoping that this proof will change her life and help her heal — but what in the fuck are we talking about again? Something involving prime numbers and algebraic interpretations of, uh, oh, who the hell knows?

As a point of comparison, science can often induce a deep slumber, but when transferred to the screen, there is usually something larger at stake: the fate of the world, a loose atomic bomb, a medical conspiracy, and so on. The conflict we see in Proof is so esoteric that we wait patiently for the ghost of the dead father to return, using his theories to enlist an army of zombies. Or something.

I realize that the previous statement makes me sound like a hopeless philistine, but I’m not the jerk off who made a movie about depressed math teachers. Without any real characterization or depth, we are meant to accept long pauses, shadowy silences, and hysterical accusations as meaningful human drama, when in fact they are little more than shopworn devices meant to delude us into thinking we have witnessed great art. In addition, Catherine is one of those people with “upper crust issues”; you know, where people have the time to ponder their shattered lives because the bills have been paid and employment is entirely optional. Surrounded by books and a grand estate, Catherine has choices (Stay in Chicago? Move to New York? Sleep all day or wake up around noon?) that would baffle anyone who actually has responsibilities beyond wading through crates of notebooks hoping to find a nugget of Dad’s wisdom.

She briefly comes to life while banging Hal, but takes a perfectly acceptable orgasm and tarnishes it with the “poor-me” waterworks. I guess I thought only chicks I screwed collapsed into a heap of tears. Even Catherine’s sister is simply a shallow distraction, as her character does little but bitch, lecture, and cross off “to do” items in her little black book, which I guess is the play’s way of saying that there are different forms of madness, and not just the obvious “take-a-shit-in-the-corner” variety. But we do end on a hopeful note, as Hal promises to work with Catherine and discover if she did in fact write the proof. Who knows, maybe they’ll even continue their torrid affair. Thank fucking Christ I won’t have to be there.