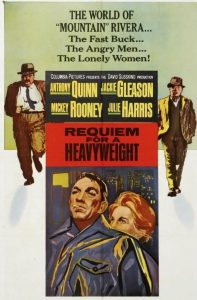

Although Raging Bull will always hold the title among depressing boxing movies, Ralph Nelson’s 1962 downer Requiem for a Heavyweight holds its own quite nicely, refusing to give us a final triumph, or even a glimmer of hope of any kind. The film considers sad, pathetic Mountain Rivera (Anthony Quinn), a good-hearted soul (aren’t they always, save Jake LaMotta?) who, in better days, danced with the nation’s best fighters, but is now little more than a battered, gravelly-voiced shell. He does what he’s told by manager Maish Rennick (Jackie Gleason), an unscrupulous, self-serving bastard who also happens to hold the most realistic view of Mountain’s future. As he tells social worker Grace Miller (the always unsung Julie Harris), a woman who actually believes Mountain can change his life:

“If you gotta’ say anything to him, tell him you pity him. Tell him you feel so sorry for him you could cry. But don’t con him. Don’t tell him he could be a counsellor at a boys’ camp. He’s been chasing ghosts so long he’ll believe anything. Any kind of a ghost. Championship belt, pretty girl… maybe just 24 hours without an ache in his body. Doesn’t make any difference. It all passed him.”

Mickey Rooney is also on board, and like Gleason and Quinn, he dials it down to the point where not a trace of ego remains. It’s about the unglamorous, the lonely, and the pain felt in quiet shadows, not a star vehicle that might turn the heads of the Academy. As penned by the legendary Rod Serling (originally a teleplay), certain clichés remain, of course, but the story courageously avoids phony uplift. And it’s not about the action in the ring, as Mountain has long passed the point of being relevant to anyone. Still, he does step in the squared circle one last time, though only to keep Rennick’s body in one piece (Rennick sold Mountain to a gangster to pay off some debts). Instead of a shot at glory, though, it’s the final humiliation of a wrestling match, where he is to portray a drunken Indian for an unruly mob.

It’s difficult to dress up a sports film (let alone a boxing picture) as anything worthwhile, as the genre has long since ceased to explore originality or insight. As everything in America can be reduced to a trumped-up victory or mindless competition (we even go head-to-head at the dinner table), we are left with “comebacks” as the epitome of national virtue. We wholeheartedly embrace second acts, despite Fitzgerald’s dictum, and cannot imagine a fictional turn that doesn’t reward the heartfelt effort. But what of the cast-offs, the rejects, and the bums?

The deluded drunks who believe they possess more skill than they actually do? And what of those who fade away with bitterness and regret; wasting precious gifts and failing to appreciate the spotlight, even if briefly held? Requiem for a Heavyweight is a judgment against the very idea of the endless parade for our heroes, for most live with racking pain, make poor choices that lead to ruin, and eventually die in some fleabag motel, little noticed or appreciated. Yes, despite the rhetoric to the contrary, we’re more Sonny Liston than Muhammad Ali, and even “The Greatest” had to become a harmless old cripple to put away the demons.