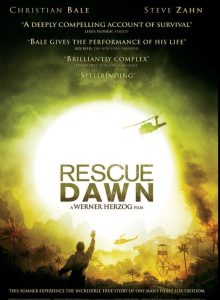

Werner Herzog is one of cinemas’ true masters; a filmmaker with vision, courage, wisdom, and just the right dose of humanity. From Aguirre: The Wrath of God to Fitzcarraldo, Herzog has deftly balanced character with sweeping action, all in service of a uniquely insightful worldview, most of which centers on the powerful obsessions that drive our species forward. And yet — a shocking, monumental yet — Herzog, with Rescue Dawn, has now made one of the worst movies of 2006; an unnecessary, stupefying bore that not only fails to generate a single scene of more than passing interest, but a movie whose script seems to have been penned in a semi-conscious, booze-soaked stupor. The dialogue, delivered in turn as flat, embarrassingly earnest, and painfully stilted, is so beneath a man of Herzog’s talent that one wonders if he left what remained of his mad brilliance on the cutting room floor. One always gives a man of Herzog’s reputation the benefit of the doubt, but my usual patience in such matters quickly yielded to a blinding rage. Genius or not, I then turned on the cinematic icon, never to return.

Perhaps I have minimized matters just a bit. Rescue Dawn is supremely, unconscionably awful; so bad, in fact, that had that famous name not been attached, I would have stormed out of the packed house by hour one, turning over tables as I went, roaring at the screen as if consumed by the spirit of the late Klaus Kinski. How Herzog transformed a genuinely wonderful documentary like Little Dieter Needs to Fly into a preposterous embarrassment is a mystery far deeper than the audacity that drove him to drag a ship over a mountain. Instead of learning more about a rich, complex human being who endured a truly harrowing ordeal in the jungles of Southeast Asia, we are assaulted by hyperbolic idiocy on the level of Rambo and Missing in Action.

It is difficult to accuse Herzog of rank jingoism given his utter clarity of understanding regarding mankind, but at the films’ conclusion — a final scene that will stand as an unintentional comic masterpiece for decades to come — we have so little invested in Dieters’ plight that he could have been coming home from the grocery store for all we care. Throughout, he is played by Christian Bale as a buffoon; a simpleminded nitwit channeling Forrest Gump through the scars and mud of war. I had always considered Bale one of our brightest stars, but with this wretched performance, he’s assured of acquiring a much-deserved Razzie before anything resembling the expected Oscar.

We have known Dieter for all of three minutes (via an awkwardly staged scene on board ship) before he is shot down during a secret mission over Laos. Sure, many of us have seen the non-fiction representation of Dieter, but its update should take nothing for granted; and surely it must move beyond expecting us to empathize with a dimwitted cipher. Dieter survives the plane crash and plays hide and seek in the jungle before being captured while leaning over to get a drink of water. It is at this time that the true horror begins, though not for the POWs so much as the viewing audience. He meets fellow captives Gene (Jeremy Davies) and Duane (Steve Zahn), as well as a few others who, because they are neither white nor American, are not granted any real identities.

For what felt like hours, the camps scenes passed by with unending indulgence in the genres most shopworn clichés: the bonding, the secret plan, the MacGyver-like use of ordinary objects, the breakdown, and yes, even the surprising display of humanity from one of the guards, in this case a midget who brings the boys a handful of rice. Throughout, Bale performs as if for the first time (did the military induct retards back in the 1960s?), and Davies makes every effort to out-mumble the likes of Brando and Montgomery Clift, even showing off his malnourished frame to put the finishing touches on the Method.

As usual, the Enemy is faceless and dehumanized, and every action is straight from other, superior works, including The Great Escape and The Bridge on the River Kwai. Yes, Dieter even files down a nail to act as a key for the handcuffs that lock the group down at night, though he does not take a ball and mitt to solitary. Dieter wants to leave well before the rainy season, but Gene is more cautious, believing that they are about to be released. As they plotted and exchanged whispers, I couldn’t help but think that at least in this case, the camp wasn’t so bad, even though I remember much worse from Herzog’s documentary. Occasionally, an American aircraft flew overhead and the guards flipped out by firing random shots and screaming incoherently, but for the most part, this was far from a torture chamber.

I guess we want them to escape, but absent from any real drama, a powerful case could also be made for staying put. And so, they kept talking, making late night additions to the plan. Then, expectedly, all is put to the test when the group overhears the guards saying that because they were running out of food, they were going to take the men into the jungle and shoot them. To hell with more preparation, my brothers, we leave tomorrow! Pardon my yawns.

The plot is carried out, though not flawlessly, and everyone escapes. All of the guards are gunned down, though the kind midget is spared (proving the rule that midgets are never killed in movies, unless they are Billy Barty). Afterwards, Gene and the two anonymous Asians go their separate ways, while Dieter and Duane make their way together. Their travels are tough, but not all that harrowing, and again, we’ve seen it before. There’s the wild ride down river on a makeshift raft that is conveniently abandoned right before it careens over the falls; the screams and shouts as helicopters pass overhead; the discovery of an abandoned village where Meaningful Words are exchanged; and yes, even the line, Just leave me here, go on without me. That’s it? From one of our most intelligent cinematic visionaries? The pair also hunt for water, shelter, and food, and of course, this means little more than long stretches of pushing back bushes and hacking away giant leaves. The setting and circumstances are what they are, and I’d rather Herzog keep embellishments to a minimum, but at some point he had to understand that while Dieter could tell a good story, his story (at least dramatically) need not be told.

What we are left with then, is a shapeless, purposeless void; a movie without any reason to exist save Herzog’s utter laziness for not trying to find a different subject to shoot. We learn nothing about Dieter, war, humanity, or even survival, and for the usually philosophical Herzog, that’s a crime against cinema. As he seemed incapable of engaging in frivolity, it’s that much more troubling that he so easily made a film that would play unnoticed on the USA Network at some ungodly, unwatched hour. And back to that ending. The eventual rescue (after Duane is beheaded in a bizarre, sloppy scene) is set to a soaring score, and he is flown back to base where CIA agents hope to debrief him about his mission.

Instead, his buddies hide him in a food cart and whisk him away to a standing-room-only welcome, where he utters some nonsense about Scratching when it itches before being carried away in a sea of applause. I’d say my jaw dropped with disgust, but as it had already done so hours before, I had to be content to rub my eyes as if immersed in a nightmare. Not only was the ending spirited, joyous, and celebratory, but it made little effort to distinguish itself from crap like Rudy. And so the circle was complete; Herzog was in fact saluting the men of war, and as such, the war itself. He did everything but fade to the national anthem and the stars and stripes whipping in the wind. It made my gut ache, and I wanted only to go home, take a hot shower, and forget I had been there to witness the toppling of a legend.