If it took losing several members of his family to the ovens of Auschwitz (including his mother) in order for Billy Wilder to see humanity so clearly, then at last we have proof that even the darkest cloud has a silver lining. I’d like to think that Wilder’s unparalleled acidity would also have resulted from a comfortable life in the country surrounded by loved ones, but feeling the personal sting of man’s murderous impulses no doubt filled in the edges with that last dab of darkness.

When he’s on, as in Double Indemnity or Sunset Boulevard, there’s no one better, especially in terms of making the bleak horrors of modernity so damned funny. His gift, then, lies in his refusal to push seriousness too far, always pulling back the bitterness just enough to stab us with a joke, or a pun, or a well-timed put-down. We’re mere dirt under the man’s nails, but he’s not so far along in the process that he can’t entertain before at last flicking us away. Ace in the Hole, the 1951 commercial bomb that so alienated viewers it had to be retitled (The Big Carnival) so it could bomb again, is in that proud, knowing tradition, only this time, Wilder saw fit not to add laughter to the mix.

Here, it’s straight, no chaser, and while it may suffer a bit for the absence of mirth, it’s so unrelentingly grim that the cynicism more than makes up for a feeling of inevitability that permeates the whole movie. And while we always know where it’s going, and with Wilder, that means straight to hell, if he can help it. We take pleasure in the journey just the same, as he doesn’t let the humorlessness get in the way of the truth.

If I were to tell you that Ace in the Hole concerns Leo Minosa (Richard Benedict), a hapless treasure hunter trapped in a cave, you’d be right to suspect that with Wilder at the helm, that same man would elicit not an ounce of sympathy before expiring with just as little fanfare. Sure, he’s exploited by one Chuck Tatum (Kirk Douglas, inhaling more scenery than usual) and left for dead by Lorraine (Jan Sterling), his uncaring bimbo of a wife, who begs to be slapped and is slapped, twice.

For all we see, the sap had it coming. He’s a decent man, sure, but running a cheap restaurant and tourist trap in the New Mexico desert is no way to treat a lady, and she’s right to see his predicament as the best chance yet to start a new life. And hell, isn’t he treading on sacred ground, plodding away in a place he knows is dangerous, all because he’d like a few more artifacts to sell to assorted rubes and weary travelers? Leave it to Wilder to make the doomed man a nitwit in his own right, and before we can blink, we’re on Tatum’s side and hoping that at the very least, this cipher down below can give the newsman a leg up in the business.

Again, this is Wilder at his most illuminating: tragedy, above all, is not about sympathy, or sentiment, or even the ties that bind, but rather the opportunity it presents to those involved. Whether that means putting a little money away, securing an election, selling a few burgers, or winning a Pulitzer, it’s all part of the game. In the end, all suffering is reduced to that moment in time where the entrepreneurial spirit is most alive. And one’s death bed is no place to close the register.

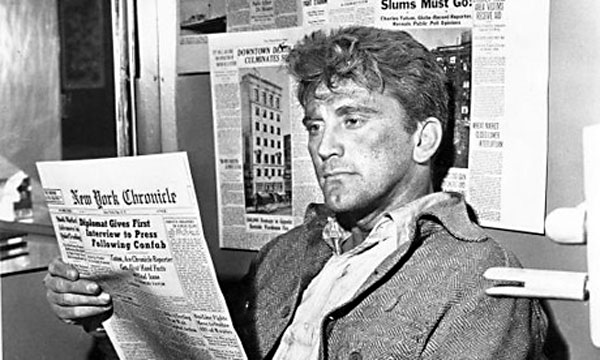

Ah, but this is Tatum’s show above all, and he works it like a man possessed; a maniacal pulp writer disguised as a journalist, though he long ago tore up his press card because it promised too much respectability. He’s a cheap whore in a crumbling whorehouse, though unlike most of what he sees around him, the lies he peddles come without the requisite self-deception. “Good news is no news”, he states, and armed with such a mantra, he’s acquired a unique ability to sniff out worthless fodder to spin into literary gold. And dammit, he’s not above wooing sheriffs and rescue workers alike to delay an extraction, either. Tatum is a role Douglas was born to play, for as much as someone like William Holden could fill the bill, he’d still be too subtle to pull off Tatum’s aggressive dance with seediness.

Tatum knows what sells and within moments, has Leo’s plight all mapped out in pictures and poetry. But in many ways, he’s a very simple man at heart. Douglas can play that simplicity to perfection because as an actor, he’s all sledgehammer amid a jetting chin and piercing eyes. As Tatum isn’t called upon to twist and shift with the wind, we expect nothing from Douglas save the yelps, shouts, and gesticulations for which he is justly famous. And so, when Tatum seems to express a bit of guilt after Leo’s death, we don’t really believe it. I’d like to think it’s merely Tatum’s way of dealing with the end of a killer headline, for any other explanation reeks of a convention the rest of the movie studiously avoids.

Because Americans themselves were implicated in the movie’s crimes, only with Tatum as the head (of the snake, clearly, given the rattler metaphor spelled out in distinctly capital letters), it’s easy to understand their disgust back at the time of its release, for what else was that decade but a period of obscene self-congratulation? We’d be fine with a bastard of a reporter spitting out his subject once he’s been mined for dollars, but how dare Wilder suggest that we’d also help dig Leo’s grave? Had the screenplay seen fit to turn Leo’s tomb into a shrine, where pilgrims came to pray, plead, and pay their respects, the rot might not have smelled so rank. Instead, the caves and their surrounding acreage are plunged into a three-ring nightmare, complete with carnival rides, hot dog stands, and dancing Indians.

That these amusements have nothing at all to do with human suffering and are, in fact, their exact opposite, is precisely the point. What on earth has a Native headdress for the kids have to do with a man developing pneumonia in a dark cavern? It would be like buying a Harley Davidson shot glass at Gettysburg. But that’s the level of disconnect on display at this, and just about every commemorative site across America. Donating a few coins to the Leo Minosa Foundation, I can somewhat understand (even if the fund is nothing more than a sweaty huckster’s pocket), but at what point does a person see the need to eat a greasy cheeseburger mere yards from the dying? Sure, the images of the rapid buildup of the grounds (where the entrance fee moves from 25 cents to a dollar as soon as the cars turn into buses and trains) are obvious and even a bit overstated, but how else could it be? Americans reduce everything to a cheap piece of crap to be slapped with a price tag and thrown on a shelf, so blatant need not be false, even in the telling.

And while we can laugh and eat and scream with delight while others die, we can further join Tatum’s assessment of backwater life. Too much outdoors, he says of his new home, though this is less applicable today than a half century ago. But the sentiment is more about “the sticks” as a whole, regardless. He also tells the newspaper’s naively honest editor, “Even for Albuquerque, this is pretty Albuquerque.” That the biggest story in weeks is a rattlesnake hunt sums up these hellholes as much as anything could, and it’s interesting how the smaller the town, the more apt it is to be defined by a single image, event, or site. It’s the logical result of a constrained geography, but it also has much to do with the state of mind.

It’s why driving off the map is more revealing than hitting major thoroughfares. Towns like the ones featured in Ace in the Hole may lack the sheer numbers of the cities, but their sense of self-promotion runs as deep. Even the local Indian curse concerning the cave feels like a tourist ploy; a way to trick those stopping for gas into staying just long enough to part with a few larger bills. Tatum understands this more than anyone, and rather than be damned, he should be praised in the same way we applaud Wilder. Tatum didn’t invent the rigged game; he’s only exploiting it as a way to feel alive. It’s what these places also understand about themselves: there has to be an angle to ensure survival. There are thousands of dots on the maps sold every single day. If someone is going to stop when all signs point to flight, it takes something more than a gas station. Jesus on a corn chip, a crashed spaceship, a dog with six legs, or a man running out of air. The only difference is how the city fathers choose to use it. Just be sure to lie with impunity while you’re doing so. The hours are long and demanding, but it sure as hell pays better. And it always will.