Fellow Cinevores:

The past is always a story recounted by liars of varying veracity. We never inhabit the past; even our own brain lies to us through lenses of nostalgia and trauma alike.

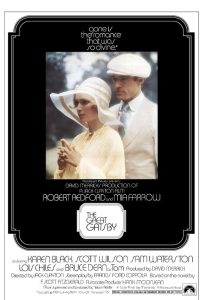

The difference between the 1974 version of the Great Gatsby and the 2013 Baz Luhrmann Gatsby is the difference between Disneyland and Williamsburg Virginia. Would you rather wince or yawn? Those are your options. One film is engaging but with painful exposition; the other is well acted but as dull as your grandmother’s house.

OK, synopsis for the non-Americans who didn’t get the story shoved down your earholes during high school: Gatsby, mysterious millionaire, throws big parties to weave his way closer to girl of his dreams, ends up dying as a consequence. Boo hoo, spoilers? Sorry- you’ve had 87 years to have heard the plot, this story is way past the spoiler tag expiration date.

Let’s go at this topic by topic:

Direction (Jack Clayton)

Far more conventional for better and worse. This is clearly a film of the naturalistic 70s- lots of zooms, pans, tracking shots. Gives the film a very leisurely pace. Luhrmann’s movie is a depiction of a dream of the story; Clayton’s film depicts a memory. Especially, there’s a lot of soft focus lenses and the mixing of faint background music, all of which adds to a slightly blurry quality to the film.

I also liked some little touches- the shots showing the preparation that goes into Gatsby’s parties. And the parties resemble actual parties that real people have, rather than some fantasy of this perfect super bacchanalia. There’s drunks, there’s arguments, there’s even- gasp! normal looking people in this Gatsby.

Script (Francis Ford Coppola)

This is a film written by people filming a story from the time of their grandparents, and it shows. On the pro side, Coppola’s got a terrific pace for catching the background conversation. On the other hand, this telling really plays up one of the favorite themes of 70s Baby Boomers, which is the theme of Nothing is Right and Everybody’s in Denial. It’s less a film about decadence and the consequence, and more a film about the facades of the elite.

The other thing I’ve realized, after seeing this story twice in four days, is that an aspect of the novel of The Great Gatsby makes adapting the film difficult in a similar way to the troubles of adapting The Lord of the Rings. Both stories have way too many scenes of denouement- from a cinematic rather than a literary perspective, they carry on way too long. It works in a novel to have this long decant, at least when you’re good at prose; you can count the ways in which an event is ended, whether in a funeral or a victory procession. But this movie carried on too long. The Luhrmann film, likewise. A part of it is that Fitzgerald spends more of his book mourning the autumn than celebrating the spring. There’s just not enough take-off, and too much landing in the source material for a cinematic adaption to be an easy flight.

Jay Gatsby (Robert Redford)

Redford makes the acting mistake of not showing the gears spinning inside his character’s head. It’s ok to be aloof and nigh-autistic for a few beats of a scene; but Redford’s Gatsby is too cool, too cryptic, too allow a bond to form with the audience. DiCaprio did a much better job at conveying the inner life of Gatsby’s mind, and his passion. Redford didn’t dip much beneath the veneer.

Daisy Buchanan (Mia Farrow)

Ok, I can get what Farrow was trying to do, and how she got her interpretation from the script and the novel. She was clearly playing to her strengths and swinging for an Oscar. Unfortunately her shtick does not make for a good love interest. Heck, Lois Chiles would have done better in the part.

Farrow’s Daisy Buchanan is all wide-eyed desperation, a nervously smiling train wreck barely able to keep up her twitchy Katharine Hepburn impression. This works great for Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby, when playing the horror of a woman’s mental unraveling. Where it doesn’t work so well is in creating a character that could plausibly serve as the object of desire for Robert Redford. Farrow’s Daisy is such a neurotic, shambolic knockoff of Blanche Dubois that I or any other sane audience member could only shout “DTMFA” at the beleaguered Gatsby. And Redford, playing a riddle wrapped in an enigma, ensures there is no chemistry between our two romantic leads.

Did you know that the novel contains almost no description of Daisy Buchanan’s physical appearance? It’s not even mentioned that she’s blonde. It’s like Mia Farrow and Carey Mulligan were playing the blind person with the elephant game. Mia Farrow takes the novel, and says “Daisy Buchanan is a dishonest, socially obssessed upper class twit who is desperately in denial, and that is what I shall play.”. Meanwhile, Carey Mulligan takes the novel and says “Daisy Buchanan is this object on a pedestal, this unattainable object, this siren that wrecks Jay Gatsby, and this is what I shall play.”. Both are true. But Carey Mulligan, playing Daisy Buchanan more from Gatsby’s skewed fantasy of Daisy, does the better job. Because she is desirable and therefore she makes the heartbreak real.

“It takes two to make an accident” is the signature line of this film, and boy, ain’t that the truth. When inscrutable cool meets full tilt method acting mania, the result is like a mosquito bouncing off a granite cliff.

Nick Carraway (Sam Waterston)

OMG It’s Jack McCoy from Law and Order! And he’s young. And I liked him better as Nick Carraway. He was less defined, but the narrator of the story works by being vague- in the novel, Nick’s lack of external comment is the skeleton key which allows him access to the inner and outer lives of the all the other characters. Tobey Maguire, by contrast, had more to the character, but I preferred Waterston’s more subdued, restrained approach. He was closer to the Nick of the book- this savvy social observer who knew when to hold his tongue, rather than an ingenue.

Tom Buchanan (Bruce Dern)

Now here’s where the 1974 version is infinitely better than the 2013 version. A three dimensional Tom Buchanan, who’s not just unceasing dickery to everything and everyone. Bruce Dern’s performance is weirdly evocative of George W. Bush- more unthinking and callous than directly EVUL FOR TEH EVULZ. He’s a little confused, very boyish, and faintly sad. When this Tom Buchanan twists the knife, he does so with the plaintive tone of apology. He makes excuses for himself. He shows actual tenderness. This is not some shallow opera villain, but a real person. Bruce Dern’s Tom is very much a “careless people- they smashed things up and then retreated back into their money”. It just further captures the original tragedy of Ftizgerald’s novel- just as Fitzgerald wrote a novel that has no truly pure or moral characters, he also didn’t write any characters that possessed true malice- only negligence and selfishness, which is true median of human evil.

Jordan Baker (Lois Chiles)

The Bond Girl again does more for the character and less for the plot. She’s this more sensuous, sexy Garbo figure- all heavy eyes and loaded stares. But at the same time, the Elizabeth Debicki performance was better at conveying Jordan Baker as an active character, one whose love of gossip and intrigue moves the story along. It goes with the general contrast I am discerning: the Baz Luhrmann version is better at the character interactions, generally, while the naturalism of the 1974 version supports more realistic, nuanced characters. Two different types of dram – one operatic, one introspective.

George Wilson (Scott Wilson)

Another standout part of the 1974 is the general emphasis on the lower classes and the upper classes. Luhrmann doesn’t care about the wretches in Queens; by contrast, Clayton pays attention to the servants, to the weeping flappers getting consoled in the wings of the party. And Scott Wilson captures all the wretched misery of George Wilson. Jason Clarke was this overwrought vision of a damned soul; with Scott Wilson’s performance, you see the descent, the religiosity. Way better.

Costumes

This won an academy for best costumes. I expect the Luhrmann version will as well. There’s a difference, again: the people in the 2013 film wear their clothes like runway models; the people in the 1974 version wear their costumes like regular clothing. Maybe it’s the whole naturalism vs. dialed up dramatricality conflict again. It’s more interesting to look at the costume designs of the 2013 version, but the 1974 version is more authentic.

I’m going to craft a neologism, the word dramatricality, adj.,: to emphasize the dramatic artificiality of a creative work for the purpose of advancing the impact of the creative work. It is similar to but not the same as theatricality; the difference lays in the motive. When one behaves with theatricality, one is acting in an exaggerated manner for the purpose of emphasizing one’s expression; with dramatricality, one is acting in an exaggerated manner for the purpose of pointing out the insincerity of the expression. It’s the difference between hamming it up to affect the rubes versus hamming it up so that the rubes can think they’re hip and postmodern and sophisticated. Got it? Let’s continue.

Music

The other academy win for the 74 Gatsby was in music. Here’s where that naturalism vs. dramatricality conflict really shines: The 1974 Gatsby plays up genuine 1920s music- tin pan alley, swooney Cecil DeMille stuff- and real 1920s dances- people do the Charleston! The Tango! There is not number in a speakeasy where a bunch of fly girls in bikinis do a booty shake to Jay-Z- because other than the speakeasy, NONE OF THOSE THINGS WERE INVENTED BY 1921. The music comes from live musicians, from record players. It really sounds like the music.

But Luhrmann’s soundtrack, while it has some misses, when it hits, it really connect to the drama. The soundtrack of the 1974 film amply serves to establish and re-iterate the scene; the soundtrack of the 2013 film goes for making the emotional impact as intense as possible. I really hope that the instrumental working of “Your Heart’s a Mess” by Gotye could get a best Soundtrack nod- it really is the best possible musical theme for the tragedy of Gatsby. Too bad it’s weighed down by the incongruities of “100$ Bill”.

Pros

The lighting is better, everything is realistic. This film gives more time and attention to all the roles. It may not be my fantasized Robert Altman version of the Great Gatsby; but it seems to depict an actual 1921 like the 1921 of our universe. Great supporting cast performances.

Cons

It gets pretty dull and it drags on too long. The whole film is like watching a bunch of conversations that you may not want to be in. And it’s very chaste- to be expected, because nobody wants to make a movie about the people of your grandparent’s generation fucking. And the lead pair- what a complete strikeout. Redford and Farrow are not just acting in different styles, they’re acting in entirely different historical periods of cinema. They never click. If you don’t have the romance, and you don’t have the decadence, and you only have the tragedy, then you end up presenting the version of The Great Gatsby that a frumpy English teacher would inflict as dictate.

I have to give credit that Baz Luhrmann’s movie will at least generate an interest in classic literature by young people. The 1974 movie helped to pigeonhole Gatsby in the canon of ‘Serious Classical Literature’, aka ‘It has to be boring to be a great work!”.

Wrapping it Up

As much as I found this movie a tonic to the woes of the Luhrmann version, I can’t recommend it too much. In the grand balance of things, there are too many better more important films that you could be watching. It’s well crafted but placid- it reminded me of a museum, interesting but not necessarily moving. I will say that it’s a good film if you want to get the look and the feel of the actual 1920s.

Fair Value of this film: $1.00, it’s worth a glance on Netflix if you like the naturalistic style of 1970s cinema. You don’t need to see it again, though.

Til the next serving,

With all my pretensions,

G. W. Devon Pack