While I have no direct evidence linking either director Zack Snyder or graphic novelist Frank Miller with the Bush administration, their booming, fascistic, searing flesh feast, 300, achieves what many had thought impossible: making a case for Bush’s war in Iraq so clear, distinct, and fanatical that I half expected an Army recruiting station to be erected at the theater’s exits. It’s the cinematic equivalent of a battleground orgasm; a homoerotic parade of tight abs, facial hair, oiled chests, leather, steel, gritting teeth, and phallic weaponry so overpowering that it’s just about the best movie ever made with jingoistic intent. It’s like a Manowar video with D-Days budget. Still, it would not be nearly enough if it merely romanticized warfare as a general rule. In order to be topical, relevant, and most importantly, successful, it must cut through the abstractions and sell the current conflict with all the bombast and mad glory that no one at the Pentagon seems to possess. With the dying embers of Operation Iraqi Freedom reaching few beyond the hopelessly patriotic, a new birth of support is needed more than ever, though Snyder’s film strikes at such a low point that its enthusiasm could be interpreted as desperation rather than inspiration. But it would have been too easy to release such a film in the wars early days, as the bloodlust engendered might have carried a relatively brief shelf life. One cannot blow their wad too quickly, after all. No, it was right to save it until now. It’s the film Bush has been begging for, and it just might save him from oblivion. If I know its target audience, I have every confidence that it will.

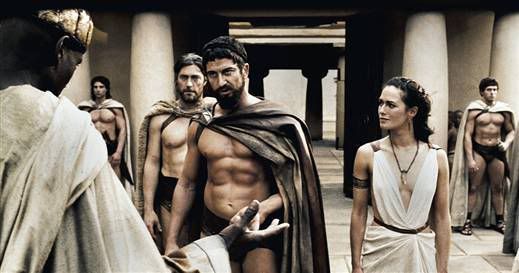

Ostensibly the historical tale of the Battle of Thermopylae, whereby a force of 300 Spartans fought bravely to their doom against a far superior swarm of Persian invaders, the film never lacks the will to play the underdog card whenever the blood needs boiling, but the moral superiority — the destiny of the superior cause — always belongs to King Leonidas (Gerard Butler) and his chosen few. That Leonidas is a stand-in for Bush is clear from the first scenes, as this man refuses to accept an emissary from Persia, which is obviously itself Bush’s very defiance of the United Nations. Leonidas is a go it alone sort, and he hits back at the messenger, which he knows will bring about a great battle. Still, Spartan law requires that the king must secure the approval of a group of mystics (called Ephors) before waging war, which frustrates his manly sense of honor. Yes, folks, the mystics are the U.S. Congress, and once Leonidas screams, “Why must the very law I am sworn to protect prevent me from doing my duty?”; the table has been set: Bush will go around Congress (using lies and tricks, brilliantly redefined as to never secure a declaration of war, and send his men to battle, the law be damned. Needless to say, the mystics/Congressmen are ugly, repellant, and literally isolated (they live on a hill,for chrissakes, as in Capitol Hill — come on guys, don’t make this so easy), which further demonstrates that the king/president is the true guardian of the people. Congress is simpering and weak; Bush is muscle-bound and bold, dashing about with flight suit and codpiece, all in service of the greater good.

Having defied the law and the effete government of Sparta, Leonidas takes his hyper masculine crew to the field of honor, which is a narrow mountain pass that will enable his smaller army to defeat what are continually referred to as hordes. And fuck of all fucks, Persians? Fine, a more accurate connection would be with modern-day Iran, but as most Americans happily argue that a turban is a turban, the leap to Iraqis is not so difficult. Amid the deafening noise, thunderclaps, and raging tempests, Leonidas bellows that their cause is for freedom, and that their deaths will secure a better future for their children and grandchildren. As he roars, assorted shots highlight sweat, grime, and rippling flesh, as well as a beard so unmistakably cock like that it all but penetrates the opposing army with its might. It’s the stereotype writ large: the enemy (Islamic terrorists) fear sex, and as such cover their bodies, while the American/Spartan forces glisten and shine with ejaculatory bluster, never appearing less than the peak of potency. Even though the American forces in Iraq were not technically outnumbered, it need not be a direct transfer to the screen. Leonidas commands a small army, much as Bush leads a miniscule coalition of nations. In fact, it is quite apparent that such unpopular wars are far nobler than larger, more coordinated efforts, as martyrdom seeks first to prove that it is misunderstood — or misunderestimated, as the case may be.

Leading the mighty Persians is Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro), the Saddam Hussein of the piece, who enslaves his people, uses fear and intimidation to rule his kingdom, harbors ambitions of regional domination, and defies the law by intimidating and invading whomever he likes. Physically, he is a far cry from Saddam (more feminine, to be sure, and wearing more bikini briefs), but by drawing him crudely, and with determined simplicity (he’s evil because he snarls and glares), he is an easy target for our righteous soldiers. No effort is made to shade these men with personalities or traits (hell, the enemies known as Immortals have no faces at all, just mere masks), but that is in line with the propaganda, as the first goal of any military is to squash individuality and stress the team above all else, as well as dehumanizing one’s foe. At one point, as the Spartans face their final engagement, they literally become a single unit, with shields upturned, as if submerged into a glob of savage bravery. But they must never show mercy (this is highlighted at every turn, as men on their backs are still speared with relish), which is what Bush himself believes, yet cannot fully articulate before less hardened crowds. The enemy is ruthless, after all, and war on this scale must dispense with such niceties, whether driving enemies into the sea (and taking no prisoners) or arrogantly ignoring long-established treaties. 300 argues again and again for unrelenting, total war, for what else can a righteous nation do when so many others seek to undermine the effort?

Even the opportunistic Theron (Dominic West) relates to our current woes, as he is any number of figures — John Kerry, John Murtha, Nancy Pelosi, Max Cleland — who handcuffs the brave leader while hand-holding the enemy (or taking his bribes). Still, he is more Paul Wellstone in the end, as he dies under the gun and is shamed as a spineless coward. Nevertheless, it is a lesson for all those who work for peace, as each has greed and lust in their hearts (rather than victory), and no one who loves freedom could ever oppose erecting a meat grinder in defense of it. The Persian cause is much like our own, where the militarists — commanding all the authority that matters, at any rate — cannot conceive of liberty without the requisite slaughter, while the lawmakers are mere fossils without the will to save civilization. Warmongers all, they seek to make their case less brutal by forever linking it with hearth, home, and yes, the children, for whips, chains, and servitude could only result from eunuch like methods such as negotiation. As Spartan women alone give birth to real men, so the American military machine — whose members are always flattered as the salt of the earth and the very heart and soul of the republic — is the sole method of achieving lasting honor. If war is perpetuated by ennobling its sacrifice, 300 all but argues for its permanent enshrinement in the human condition; inevitable, justifiable, and pure. It is not to be avoided, but indulged; it is the lone avenue to our better selves.

Leonidas eventually dies with his men in a hopeless final battle, but this is not to be interpreted as America’s loss in the Middle East. Instead, Leonidas’s death is Bush’s self-sacrifice, though he is substituting his presidency for his actual life. Because Bush believes that Iraq will eventually produce success, he has proven willing to risk his entire term of office for history’s final judgment. And if Bush’s gamble mirrors Leonidas’s own example, future generations will hail Bush as a hardened genius not quite suited for his own flaccid times. Such men as Bush will at last be appreciated in the world to come, which could only be the motivation of one who conceives of himself as a savior. Did not Bush claim to seek God’s guidance? Has he not been quite forthright about his conversations with the Almighty? Bush’s historically low popularity rating is a heavy burden, to be sure, but one worth bearing if Iraq is to be the 21st century equivalent of Jeffersonian America. I’ll be damned if Leonidas didn’t also look skyward as his death approached, knowing full well that though his earthly body would be riddled with arrows (leaving a glorious crucifixion pose; you know, to erase any lingering doubt about the film’s message), his soul would live on in the spirit of his people. Tell others what happened here,as Leonidas instructs the one-eyed messenger (and narrator), and so he does, producing an eternal legend that blurs history into myth, recast as ultimate truth. The ambitions of our current commander in chief are no less grandiose.

Also check out another review by WAX here. Matt’s reply to hate mail is here.