Jean-Pierre Melville has had the best years of his career lately, with the Criterion release of several of his films (Le Samourai, Le Cercle Rouge, Bob Le Flambeur, Les Enfants Terribles) and a resurgence of interest in the work of this mercurial and reclusive character. As Melville (he changed his name to honor his favorite author, Herman Melville) put it, I have a bloody awful character. Melville was famous for being impossible to work with — abusive, and temperamental to his entire crew, especially his actors. He felt indebted to nobody. Possibly this is because he clawed his way into the industry, built his own studio, and exercised absolute control over his product, in defiance of the French film industry that regarded this upstart as an amateur.

He was one of the fathers of the nouvelle vague before there was a vague to speak of. The plots were never that revolutionary, involving crime dramas, heists, and so forth. What made his work exemplary was the execution. Melville was a master of tone and style, and had control of all aspects of the film: author, director, cinematographer, and even set designer. Even if Orson Welles had not existed, Melville would have invented the auteur theory out of sheer dictatorial need. His independence and technique informed the vanguard of the French New Wave proper, and created seminal works of austere beauty that were quietly tragic, yet devoid of sentimentality.

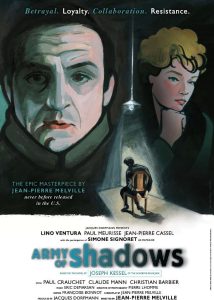

Which brings us to his masterpiece, L’ Armee Des Ombres. On its surface, this is a precise examination of the French Resistance, shot in a documentary style on location. This is in keeping with the style of his other films; somber, meditative, and colored in grays and shadows. Truffaut once noted that it is impossible to make an anti-war movie, and Melville seems to have heeded this advice in making his film relentlessly bleak and devoid of any big speeches or action set pieces. A small cell of Gaullist resistance fighters, led by Phillipe Gerbier (Lino Ventura) labors to resist the Nazi occupation of France, and the Vichy collaborationist government.

They have no names, no families, no friends, speak very little, and live with the understanding that they will all die fairly soon. They move from safe house to safe house, plotting the next saboteur action. Truth be told, very little works in their operation. Team members are routinely caught, tortured, and executed, never accomplishing the missions they were planning. They spend more time running and killing each other when betrayal is suspected than any actual, you know, resisting. The cool and unsentimental technique of Melville places you in a very tedious reality, with no actual plot arc, and no triumphant coda to anticipate. You, as with the resistance fighters, are placed in a patriotic vacuum.

Melville was a member of this resistance, and so was well placed to make a documentary style film about it. It will dawn upon you, however, that he had no intention of creating a film about the resistance, or even about war. Apart from the Nazi occupation, Melville noted, “I excluded all realism.” This film is about that vacuum — of patriotism, emotion, destiny, of any human tether. The resistance fighters exist without any proof that their efforts will be of consequence, or that they will earn any reward apart from a painful death on a concrete floor. What becomes of the human spirit when cut off from the past that one has known, and a future that is no longer promised? The opening shot of German soldiers marching upon the Champs-ys-es sets this tone for the duration, the surrender of an entire nation. The Resistance fighters are adrift in a sea of despair, their resolve fed by nothing more than the blind faith that their actions are right, and their sacrifices will matter when their nation is reborn.

The acting within this film is a masterpiece in subtlety, as it must be when the characters are among enemies and traitors. Rather than using explosions and battles to produce tension, the director employs quiet and nuance. When Gerbier escapes from the Gestapo headquarters, he ducks into a barbershop for a shave. His manner seems to betray him, as one cannot disguise that a shave in the middle of the night with soldiers looking for an escaped prisoner outside is a tad difficult to believe. Gerbier quietly submits himself to a barber with a razor in hand, the portrait of Petain on the wall. Without a word, the barber completes the shave, and before his client leaves, he hands over a dark overcoat, keeping Gerbier’s lighter one. A nod of understanding between them, and the man leaves.

There is little action to speak of, and this is a calculated effort on the part of the director to hold this impossible level of tension until we begin to share the despondency of the characters. A big assault on a Nazi fortress or the assassination of an officer would let the audience off the hook, and subconsciously allow the viewer to think that such situations can be neatly dealt with in the space of 2 or 3 hours. When watching Army of Shadows, you never get the feeling that the war ever ended. You enter the story in media res, and remain there, trapped with the Resistance, which is only fair. After all, they do not know whether they will live another day. Why should the audience expect to exit the state of mind the film manages to create? Most films, war or otherwise, deal with simple heroes and clear victories. This one has no such illusory aspirations, as it draws you closer to the world we truly live in, one filled with shadows.

This was the greatest of Jean-Pierre Melville’s films, though its release was sabotaged by the political atmosphere of the time. De Gaulle was seen as a reactionary by 1969, and anything bearing a Gaullist scent was savaged. It was not released in the United States until 2006. It will take some time for this to be regarded among the greatest of films, but its perfection will make this inevitable. Criterion released the film in May of 2007.