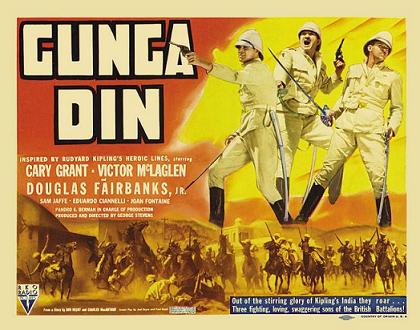

George Stevens Gunga Din is the sort of unapologetically ethnocentric adventure picture they don’t dare make anymore; a rousing, two-fisted flag-waver for all those who found Birth of a Nation a bit light in the laughs department, or who never tired of watching the Union Jack raised again and again over its proud colonial empire. It’s a film impossible to imagine in a post-Gandhi universe, yet one so swashbuckling in its naive arrogance that it all but commands an ear-to-ear smile. And so it does, what with Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen, and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. aboard as indestructible friends first, dedicated soldiers second, and faint, longing lovers only when the guns fall silent.

Fairbanks, as Ballantine, is about to leave the service for marriage to Emmy (Joan Fontaine), but the few scenes with his wife-to-be are so strained and uncomfortable that it’s always clear he’ll dump her for greater glory with the fellas (who mock this heterosexual involvement from the shadows). It doesn’t help that he kisses her like she’s a slab of balsa wood. Worst of all, she wants to domesticate poor Ballantine, which means she’s even more of an enemy than the hated Thuggee band, a death-obsessed cult that numbers only in the hundreds, but is meant to stand in for all of India, as befitting the Hollywood racism of the time. They worship Kali, a cruel mother who demands that her followers strangle, shoot, and stab every last Englishman before, presumably, taking on the world. No attempt is made to understand these people; it’s enough that they are brown, bug-eyed, and devoid of humanity. The rest is just trivia.

As the story begins, the savage Indians are butchering the benevolent Brits as they seek only peace and quiet by which to loot and subdue the entire country. Our three heroes are joyously throwing a few bearded heathens out a window, which quickly establishes them as loveable lugs who can’t help but get into trouble. Their mischief even extends to attempted murder of an officer, as they so poison Ballantines’ replacement that he’s sent to the hospital. But it’s all in good fun, which is reflected in Grant’s spirited portrayal of a lad with contempt for every rule save the code of honor involving his brethren. He wants to fight for king and country, sure, but he’s also after assorted Indian treasure, whether it’s a buried cache of emeralds, or a lost city of gold, which is just where our dashing trio will make their final stand.

Grant (as Cutter) is swiftly jailed for his pranks, but escapes with the help of an elephant and the ever-faithful Gunga Din, a water boy who lives to serve, so long as he’s serving the very men who have cruelly enslaved his homeland. Without hesitation, Din smashes the prison walls, frees Cutter, and leads him to the gold, which just happens to double as the mountain headquarters of the Thuggee faithful. Needless to say, Cutter is captured, though Din escapes to inform the other men. And so begins the real adventure of cheeky imperialism.

But what of our sweet Gunga Din? Played by Sam Jaffe (a Russian Jew!) as if he were the founder and CEO of Hollywood’s top supplier of bronzer, he’s like Marty Feldman in a diaper; always wide-eyed, shuffling, and in utter rapture at the prospect of shooting his own people for the British empire. He is devoid of any real trait save his lust for service, and even when no one is looking, he’s practicing the salute and marching technique of the overlord. That said, and despite his status as the Uncle Tom of the Orient, he is unfailing in his charm; more loyal pet than person, yes, but so damned cute we can’t help but root for his assimilation into a world not remotely his own. By the rules and logic of the day, he won’t survive the movie, but deep down, we can imagine a last-minute airlift off the mountain, a frantic wave goodbye, and a cut to his later years at a top prep academy, somehow more British inside and out.

It’s likely the only reason this movie was even made, and it all but justifies a continued presence in the region from then until eternity. Left to their own devices, the Indians resort to sheer brutality, unprovoked attacks, and mindless devotion to an effete megalomaniac named Guru (Eduardo Ciannelli) — the cruel sadist who warmly channels Brando’s Kurtz, keeps a pit of snakes to reinforce even deeper stereotypes, and manages to steal off with whatever self-tanner Jaffe left in the trailer. There’s not much room for discussion when the Other is either murderously mad or childishly ignorant, but I have never let cultural elitism stand in the way of manly entertainment. Dehumanization has never been this much fun.

Once all the pieces are in place — Din’s destiny as the unexpected savior, the women dispatched to the sidelines, a few final snarls by the nasty Guru — we await the final assault on the Indian fortress. It’s meant to be a trap so that the British army is butchered with no means of escape, but Din, already dying from a bayonet wound that would have felled lesser men, scales the temple to blow his prized bugle, thereby alerting the approaching troops. The sound of the horn lets loose a tidal wave of murder, as the screen is quickly enveloped by dust, debris, and dying Indians. No sane man would attempt a corpse count at this late stage, but it surely ranks with any film of its type, then and now.

Horses fall, bodies tumble from their perches, and in one orgiastic burst of bloodlust, the only good Indian becomes the proverbial dead Indian. Cutter pierces the air with one last jab at Oriental cruelty, only to watch his beloved friend (mascot) die for England’s sins. And for his sacrifice, Din will be posthumously inducted into the British army, given a suitable rank, and carried away on a stretcher, remembered forever in a poem by Rudyard Kipling, who is conveniently on hand for both the final battle and Gunga’s martyrdom. “You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din”, Kipling’s ode concludes, which might be touching if we had any idea who the little man actually was. For once, a good time trumps a lesson learned.

Leave a Reply