Jim Henson most famously created The Muppet Show, a thoroughly entertaining variety show that became the necessary stop for B-list celebrities and has-beens who wanted to slow their descent into obscurity. Leaping at the chance to ham it up alongside a rich cast of puppets cut from felt might seem like a strange choice, but anyone who witnessed the wit and irreverence of its stars could understand the appeal we’d have to wait for the advent of Pixar before we got something designed for children but targeted squarely at both them and their parents.

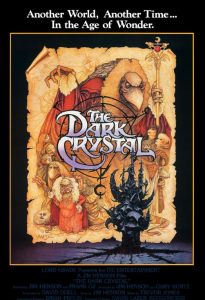

The muppets formed the cornerstone of my limited childhood television time. I figured all plush dolls spent their time singing and dancing with a hand up their ass all day long, because I was six. The rest of my TV time was made up of cartoons like Transformers and GI Joe, where all struggles were fairly simple, short, there was neither death nor suffering, and all problems were resolved within 25 minutes plus commercials about toys and more cartoons. In 1982, Henson created the feature length fantasy The Dark Crystal. I eagerly went along to the theatre to see it, anticipating the further adventures of the muppets as they pursued the mysterious sounding precious stone. I was in for a surprise.

After the theatre darkened, orchestral music began, heavy on the horns and drums, and the screen was filled with a dimly-lit image of a castle on a barren plain. It was clearly nightfall, but I was given the impression that sunlight would scarcely do the scene justice. It was here that I learned the power of cinema to set a mood by various means, and my heart sank as I realized the bleakness of the conflict being established. I also did not see Fozzie Bear, who no doubt would have been raped and mutilated if he tried his stage act in this setting.

One thousand years ago, the magic crystal cracked, and two races appeared  the wise and gentle Mystics, and the cruel Skekses. Since that time, the world was plunged into war and ruin, as the Skekses pillaged the land for their benefit. After a millennia, the triple suns of the world were to come together in the Great Conjunction, which the Skekses would harness to achieve immortality, and lock the planet into a twisted empire that would never be renewed. It is up to Jen the Gelfling, last of his race, to stop this from happening. So, basically the usual good guys and bad guys struggle that will end when the good guys win, the bad guys get their comeuppance, and the credits roll. At least, thatÂs what I thought. Those of you familiar with this classic film are well aware that all expectations were defied.

The Dark Crystal is an overwhelming work of supreme imagination. ThatÂs where the Muppets comparison ends. The audience is immersed in an alien world. There are no humans here, just plants and creatures that are wholly unrecognizable. There are no digital effects (I shudder to think what George Lucas would do with this material); just extraordinary sets and costumes that form entire ecosystems. In one astonishing shot, you see plants that fly, trees that walk down to the river for a drink, and a doglike creature that is eaten by a hillside. For these and many other reasons The Dark Crystal is an excellent film for a child to watch if you do not want them to become a shithead. The imagination of a child can be inspired by these images, but the action is also a great deal more mature and darker than most kids entertainment.

Jim Henson shows the young crowd a great deal of respect in various ways. Firstly, the world of The Dark Crystal is a fantastic but natural world. Just as the imbalance brought on by industry and rapid human expansion and consumption of resources threatens every species on Earth, the overuse of resources by the Skekses and disregard for preservation has turned the fantasy world of The Dark Crystal into a sewer. Thus, environmentalism takes center stage, and plants the seeds for understanding an individualÂs place in a world that is, at its most basic level, one ecosystem.

Secondly, death is a constant companion. Similar to Watership Down, death becomes a pervading and vital part of this brutal story. Though this is a fantasy world, all beings are born and must die, from the creatures hunted by predators in the forest scenes to the sentient beings that war with each other. There are shocking moments here that still fuck me up to this day, like when the magnificent landstriders are painfully killed by the Garthim. Death cannot be rationalized or prevented; it is a part of the circle of life.

Also, genocide is a plot point. The Gelflings have been slaughtered, introducing the concept of genocide to children everywhere. An ancient prophecy declared that a Gelfling hand will be the one to restore the Crystal, and so the Skekses labor to murder every last one of them. This has a pretty clear parallel to the killing of the first born of Israel, and though Jen the Gelfling must wander the countryside in his quest, he lacks MosesÂs big mouth or the self-righteousness of Jesus. So, I categorize this as a secular genocide rather than a biblical rip-off.

Slavery is a plot point, too. In one devastating scene, the Garthim raid a podling village and capture scores of them, hauling them away for essence-drainage and turning them into slaves for the emperor. Pretty dark stuff, especially when a Gelfling reveals that these raids happen from time to time. So they sit there and wait to be raided, instead of running away to the hills, or burning the Garthim alive when they visit. As it turns out, some people just donÂt do much to avoid being turned into slaves.

There are clear political parallels between the leading races the Skekses are intended to be evil, slave-driving, and power-hungry, so basically they are capitalists who harness the power of natural resources for profit. Natural resources include the pod people and anyone else who can be drained of their vital essence to keep the Skekses young, beautiful, and strong. In one scene, a captured pod person is locked into a chair and a mirror is moved into position in front of the person to reflect the Crystal’s rays into their eyes. The person is hypnotized, drooling, and drained of their essence, or will to live, looking like they have been watching television for hours and are now willing to buy whatever is being advertised in front of them. The capitalist Skekses couldn’t be happier, though the essence of the ignorant podlings is weaker than Gelfling essence obviously the podlings just donÂt have significant buying power.

The Mystics are intended to be gentle and wise, well-versed in the ways of natural wizards’ hippies, basically’ who spend their entire days smoking, playing guitar, and drawing pictures in the sand instead of doing something about those evil Skekses who are, like, totally harshing everyone’s mellow. They do nothing, produce nothing, and when it comes time to bring an end to the Skekses dominion, they summon someone else (with a deep-throated call that sounds suspiciously like a didgeridoo) to do the work.

So, it is not the archetypes of the right or left wing who are inherently evil. Instead, what causes the suffering is the imbalance between the two. There are no clear villains or heroes (apart from the Gelflings) the Mystics and Skekses are two lost sides to the same beings as mentioned, but the solution is far from simple. A standard good vs. evil resolution would require the Skekses to be killed off, which was the solution my six-year old mind was hoping for. Then, in one scene, Kyra the Gelfling mobilizes the animals to drive the Scientist into the elevator shaft and incinerate him. Yay, right? Cut to the Mystics slowly ambling toward the castle, and in a flash, one of them dies, engulfed in flame. The potential catharsis of killing off a sadistic enemy is nullified in an instant.

Instead of all-powerful villains, the Skekses are incompetent doofuses who seem to hold power with little more than industrial ingenuity and ruthlessness. Their infighting has not served them well, and they are actually dying, numbering only ten at the start of the film. The first scene with them involves the death of their emperor, and the subsequent power struggle between the Garthim Master and the Chamberlain. This rivalry inadvertently results in destroying their plans by saving the Gelflings. There is a discussion to be had here with children about how even powerful enemies can be divided, as well as the drawbacks of being overly concerned with ritual. The swordfight, incidentally, involves striking a phallic stone. It may seem funny that a childrenÂs movie has a scene rich with castration symbolism, but that is exactly what vanquishing oneÂs foe involves.

Most films resolve their struggles and tie up all loose ends by killing them. This is simplistic and impractical in the real world, where the bad guys often get away or do not suffer a violent recompense. What we get in The Dark Crystal is less cathartic than a bloodbath, but most battles in real life end in compromise, occasionally even an understanding between the warring factions. It’s a fantastic yet realistic story, though, meaning that it’s enjoyable and thought-provoking and also that the allegorical possibilities are limitless, so it stands up to numerous re-viewings, like any good kid’s film should.

The Dark Crystal was a commercial failure when it was first released, as parents who were expecting the Muppet Show Takes Middle Earth and didn’t see past its violence and chaos. Because of their protective instincts, parents are generally neurotic and conservative, with a blind eye turned toward the larger picture, believing their innocent spawn will be forever shielded from violence and complications. Children are better served by preparation, though, and there is no better preparation for adult life than complicated and imperfect stories that mirror our impossibly cluttered and complicated lives.