2008 Denver International Film Festival

My America is less about the upswing than the downward slide, where the underdogs strike too sentimental a chord because even, they have a fighting chance now and again. My America sees more truth in any one moment of Richard Nixons rambling, self-pitying farewell speech than in the entirety of JFKs soaring, inspirational inaugural address. My America is not the thin, sexy King, but fat Elvis, face down in his own vomit, choking down that last bit of the dignity train that long ago left the station. For all the hope we inspire, and all the dreams we set in motion, Americas best, most lasting stories are in the shadows; not among those who give breath to our better angels, but rather in the mire and muck of the men who never deigned to try. Its among that set that gives rise to a more recognizable national creed — where the past is the only manner by which to suffocate the future, where moving on is death, and starting over an admission that it, and all that implies, just isn’t working.

So, take your Rocky, or your Rudy, or the member of your choosing from that gallery of the plucky downtrodden made good. I, on the other hand, will cast my lot with Randy The Ram Robinson. The Wrestler. A legend by virtue of being exactly what a legend never was, or could ever hope to be.

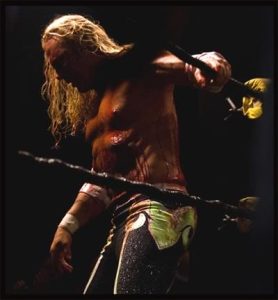

Darren Aronofskys The Wrestler, a film that on its face doesn’t sound like much at all, is not without convention, or cliche, or even a hint of familiarity, but its brilliance is not in its ability — or desire — to revolutionize the medium. Through one simple character, the washed-up slob that is The Ram, America itself is laid bare (and where Jersey has never looked so Jersey). And who knew that when the chips were down, Mickey Rourke would come to set things right? His performance is a revelation to be sure; a realization so penetrating, wise, and achingly authentic that it deserves to sweep Oscar off its feet.

It is greatness in raw, unflinching defiance, both as a physical embodiment and through sheer emotional resonance. It’s the epitome of the Methods still unsurpassed approach to the art. Rourke never overreaches, or plays to the cheap seats, or asks us to find him appealing. His faded has-been is a bastard through and through, as well as the sort of man incapable of breadth, scope, or even a moment where he isn’t out to prove his worth through the channel of an appalling self-loathing. His is the vanity of utter stasis; where, preserved in amber like a prehistoric insect, he bathes in nostalgia to keep the world from penetrating his tomb. He lives as he did, stunted for all time, unable to grapple with the parade that long ago passed him by. He’s a muscular, scarred Norma Desmond; the ring his musty, cobwebbed estate.

Randy is a wrestler down to his marrow, which means that in a world forever exposed as insipid, fraudulent sport, he knows of little but the performance. How else to explain that as an aging slab of beef, he’s still injecting and ingesting, sculpting and bronzing, all in the attempt to maintain an illusion? He’s forever chasing that long-diminished high from the 1980s, a decade he speaks of with near-fanatical reverence (killed off by that faggot Kurt Cobain). He wrestled the best, was the best, and perhaps, so long as Ratt, Quiet Riot, Cinderella, and Accept blasted through the speakers of his ridiculous van (doubling as living quarters when he’s locked out of his dilapidated trailer), he’d never meet the reaper. No scene better demonstrates his immersion in those perceived glory days than a pathetic appearance at a wrestling convention at a local American Legion Hall.

Only convention is far overstating what is in reality an ad hoc gathering of burnouts and but a few straggling, sleepwalking fans. The moment Randy sets up his display, complete with VHS tapes of previous battles and a Polaroid camera for autographed shots, we know that he’s a mere ghost on a landscape he no longer understands. He’s like your grandmother who still refuses to get a computer, or the holdouts who need to be reminded that come 2009, those rabbit ears will no longer power up the old picture box. Sure, he’s not wheelchair-bound or asleep at his post like others in that cold, depressing room, but he’s a heart attack away from far worse.

Am I saying that The Ram suffers one of those life-altering medical dramas so common as to be obligatory? Yes, there is a collapse in the locker room and yes, he even has a long hospital stay (and bypass scar to show for it), but rather than redeem the poor sot, it makes him even more delusional. The eventual visit to his estranged daughter, as much as it flirted with the unnecessary, rang true not because it broke new ground, but because it demonstrated yet again how this man views his surroundings. Not only does he fail to know a thing about his child, he has no real clue about how to conduct a relationship that isn’t scripted.

The scenes of attempted reconciliation are less by the book than the films continued push into Randy’s nature. His reactions and gestures are unoriginal because he’s relying too heavily on what he believes to be his duties as a dad, rather than anything real or time-tested. In the absence of mentoring or observation, a man relies on the culture at large to dictate behavior. Even that’s too generous, however. If he’s refused to acknowledge a single national event or influence for over twenty years, what makes you think he’s considering cutting-edge parenting trends? Randy is the Everyman for any number of reasons, but never more so than with his unarticulated, but steadfast belief that whatever (or whomever) doesn’t conform to his perspective is to be considered not on its own terms, but summarily dismissed and forgotten.

Still, lest anyone think this is a dry, humorless soap opera, it bears repeating that The Wrestler, for all of its pathos and insight, has moments of great fun and rich laughter. The wrestling scenes (no flashbacks here, just the contemporary, dreary venues of the aging set) are both hysterical and vivid, demonstrating technique (how does a man hide a razor blade to cut his scalp?) and showcasing set pieces so bizarre as to seem unreal. Or less real than usual. Randy’s fight with the Rabbi-looking dude, for example, involved barbed-wire, panes of glass, thumbtacks, a staple gun, and an audience members artificial leg. Rourke’s stint as a boxer is key here, as he struts and slams like a true champion, impressing anyone who thought he was over and done.

Sure, Mick is beyond grotesque, but who better to portray a man puffed up and padded by years of self-abuse? That such grand displays are for little money and even smaller crowds makes it all that much more desperate. But to see the promotion teams at work, one would think the Rumble in the Jungle was imminent. In the winds, there’s talk of a revenge match between The Ram and the much-hated Ayatollah (waving his Iranian flag, despite being a black dude from Arizona), and though the film pushes towards that climax, it’s never out of a need to provide that age-old trumped-up victory. After all, how could a rigged game even count as a victory?

Another great scene, destined to be one of the best of the year, occurs behind the deli counter of a strip mall grocery store. Randy takes the position after his heart attack, and watching him learn the trade breaks the heart, even while a smile beams. It’s a kidney punch for anyone forced to start over, or accept less, or work beneath one’s station, though for Randy, its not so much a step down as a retreat into the anonymity he couldn’t bear to face. And yet, from the moment we follow him through the store (filmed exactly like his long walks from the dressing room to the arena floor) to the excited way he flirts with customers and scoops out potato salad and the like, Rourke’s presence proves unshakable.

At that moment (there are others, but none quite like this little tango), we see how the finest performances are those that understand faces convey much more than words ever could. Randy is cragged and racked with pain, and his self-involvement eclipsed only by his striking ignorance, but not so much that he howls like Lear at life’s betrayals. What would he say, even if empowered by atypical eloquence? No, he’d rather ask a neighbor kid to come over to play his archaic Nintendo system, not for thrills or excitement, but because it’s the only available product that boots up a wrestling game where he’s forever the star. When the boy counters with newer, better game titles, Randy is dumbfounded. Yeah, but what about my game? Here again, no one can move on.

So, The Ram’s just another lummox, right? A buffoon that earns every ounce of derision and pity thrust upon him? Perhaps, but with all the absurdity he appears to represent, there’s a powerful simplicity to the man that also speaks to greatness. Not in the traditional, narrowing sense, but out of deference to the once common ideal that treasured the man who knew his limitations, and sought nothing but a small stage on which to peddle his wares. Randy is, above all else, an entertainer, and because everyone in the pro wrestling world — fan and fighter alike — knows the score, it’s an expression of populism’s essence: joy for joy’s sake without a trace of pretension. Low-brow and unsophisticated, by all means, but nothing hidden behind the curtain. It’s an uncomplicated approach that’s no longer in fashion, much as any expression of emotion these days is usually met with ironic scorn.

Political hatchet man Lee Atwater once said that wrestling was the most honest sport because it lied like hell for all the world to see. Randy would agree. Thankfully, our last image of him is as a wounded warrior in flight; not yet dead, though only barely alive, and seemingly ageless and transcendent. It may have been his last turnbuckle, or one of many to come. There’s never closure on such a creature; to kill him would be to extinguish what’s best in ourselves. The man at journey’s end: alone, without salvation.