Dying before he was sixty seemed like a fitting final action for the maverick film-maker Sam Peckinpah. Better to burn out than fade away and all that. For whenever Sam was in town the rage-filled stories of excess flew thick and fast, tales that included wild on-set bust-ups, legendary alcohol and coke consumption, budget blowouts, and bitter clashes with studio execs, all stoked by media outrage about the graphic nature of the blood-soaked final product.

Peckinpah was a tyrannical director, capable of firing more than thirty crew on any given shoot, and yet inspired fierce loyalty as he battled to deliver unmolested artistic visions of a particular type of dysfunctional man. The result was some of the most vivid and uncompromising films of the era, films that often centered on battle-hardened adversaries hunting each other, amoral men on bloody missions of self-destruction, and tormented loners determined to do things their own way. Men who were not only lost, but had no idea if they even had a home.

“Sam’s films were always looking for something special,” regular cohort James Coburn says in the 2005 doco Passion & Poetry: The Ballad of Sam Peckinpah. “You got to do work that you couldn’t do with other people… He not only allowed you to take it out to the edge, but sometimes he would force you out there. He might be a nasty bastard, but at least he’s truthful about that… Each film he made was a sacred enterprise. He devoted not only his time and attention, but his heart and being. Some of them were worth it, some of them weren’t, but they were all interesting.”

The Wild Bunch (1969) ‘I want them all back here head down over a saddle.’

I guess if Wild Bunch were remade today our main characters would be ethnically diverse. One of ’em might even be a woman. Back in Peckinpah’s day such tedious considerations could be ignored, leaving him free to direct charismatic, convincing actors (e.g. Ernest Borgnine, Warren Oates and Ben Johnson) while reducing the female presence to that of Mexican whores. Indeed, Wild Bunch is the perfect example of what’s been lost in modern moviemaking, standing as a lasting testament to the clear (if blood-spattered) vision of its hard-living auteur. Now well over half a century old, it remains an epic meditation on violence, obsolescence and the fierce code that bonds certain kinds of men.

With this groundbreaking flick, Peckinpah also ran headlong into the same finger-wagging bullshit that Tarantino would face twenty-odd years later with Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction i.e. the excessive use and glorification of brutality. My answer to such objectors is to politely suggest they fuck off and watch Mary Poppins instead. Wild Bunch does have a nihilistic flavor, though, best illustrated in an ominous early scene in which a bunch of kids giggle over a writhing pair of ant-covered scorpions that they’re about to set on fire.

We begin in 1913 Texas. Pike Bishop (William Holden) is the leader of a gang of aging outlaws intent on robbing a bank. Unbeknown to him, his former comrade now turned deputized pursuer, Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), is lying in wait with a load of bounty hunters. The bank robbery is a disaster, netting the gang some bags of metal washers while leaving about a fifth of the townsfolk dead. Worse, they lose a few men in the botched raid, causing them to flee across the border with the ‘Judas goat’ Thornton hot on their trail…

This tremendous opening shows Peckinpah’s unsentimental, uncompromising nature. It’s masterfully depicted with bullets thudding into chests, bodies falling off roofs, bystanders getting mown down and horses crashing through shop windows. No western had ever been so graphic and in one foul swoop a new age of bloody gun violence was ushered in.

Clearly, the money-obsessed Bishop and his men are no angels. They’re committed criminals, happy to use the oblivious residents as a human shield. They will also execute a blinded gang member to avoid being slowed down. Bishop, however, is a long way from a bloodthirsty savage. “We gotta start thinking beyond our guns,” he says. “Those days are closing fast.” But although he’s a clear-sighted, unhesitating killer, he also strongly believes in comradeship, even if that ultimately means self-destruction. “When you side with a man, you stay with him, and if you can’t do that you’re like some animal. You’re finished.”

Like Sergio Leone, Peckinpah had a real flair for bringing to life a man’s world in which action set-pieces, economical dialogue, superb stunt work, a vibrant grasp of history and the ability to illustrate character predominate. Peckinpah also had an eye for populating his group scenes with memorable faces and local color.

Still, his main interest is masculinity and Wild Bunch excels in this regard. His anti-heroes fight, drink, rob, frolic with hookers, party hard, play pranks, lust after gold and slay without apology (“If they move, kill ’em”). There’s no balance provided by the ‘good’ guys, either. Thornton’s posse is a motley crew of squabbling lowlifes while the gringo-hating Mexican army that Pike tangles with is filled with corrupt, untrustworthy barbarians.

Wild Bunch is so fucking manly there were times I had to put down my knitting and just sigh. It leaves us with no winners and losers, no victory of any kind. It’s the cinematic equivalent of ant-covered scorpions being turned into a bug bonfire.

Straw Dogs (1971) ‘What the hell is wrong with you people?’

I was always disappointed by John Carpenter’s post-Thing output. Stuff like Christine, Prince of Darkness, They Live and In the Mouth of Madness doesn’t cut it for me. It’s as if the revulsion and stinging reviews that met his hard-edged 1982 sci-fi/horror masterpiece broke something in the man. His verve was never quite the same.

Peckinpah followed up the furor surrounding Wild Bunch with the unconventionally gentle The Ballad of Cable Hogue. However, he quickly appeared to decide that such mildness didn’t represent his true artistic nature and jumped back into his rough-hewn saddle. And so we come to the troubling Straw Dogs, a mysteriously-titled flick that was probably even more controversial than his breakthrough hit. It’s an essential watch, underlining that Wild Bunch was no Tobe Hooper-style flash in the pan.

David Sumner (a prime Dustin Hoffmann) is a meek mathematician, trying to cope with the simmering undercurrents of hostility in a Cornish village. He’s moved there on a university grant with his sexpot wife Amy (Susan George, never better) in a bid to temporarily escape the growing social unrest of early 70s America. As the saying goes Better the devil you know because this particular village is chockablock with misogyny, predatory men, bullies, animal cruelty, passive-aggressiveness and excessive drinking. Not to mention a child-molesting idiot, ostracism and low tricks. Even the rat catcher is a tittering fuckwit who’ll ask you if you’ve seen ‘anybody get knifed’ before stealing your wife’s panties.

Straw Dogs examines the latent violence in man, partly by presenting David as unmanly. A chump. Or at least that’s how the locals view him. They don’t like his clothes, his way of speaking, his short stature and his intellectual job. They might call him ‘sir’ to his face and take their hats off in his home, but their respect is the thinnest of veneers. Most of all, they resent how this ‘Yank bastard’ has got his hands on one of their best girls. Amy is little help here, sarcastically calling him ‘tiger’, complaining about his lack of DIY acumen, and obviously thinking less of him for refusing to confront the horrible, intimidating bunch of builders working on their temporary home. Their marriage isn’t quite a sham, but it’s clearly fractious, full of needle and petty digs. “Don’t play games with me,” David warns her, but Amy doesn’t heed the inherent danger in her behavior.

This brings us to Straw Dogs‘ other concern, which is female sexuality. The first shot of Amy is her nipples doing their best to poke through a thick white sweater, immediately placing her in a sexualized context. She’s aware of her affect on men, but there’s some truth in David’s observation when he tells her: “You act like you’re fourteen.” She complains about the builders’ ogling and yet parades around her house naked, knowing they can see in. David suggests she wears a bra and “shouldn’t go around without one and expect that type not to stare.” Of course, this wanders dangerously close to the old ‘asking for it’ cliché, but Amy does welcome some of the attention. Her eventual assault, in which she initially resists the first rape and then enjoys the sex, only complicates matters. It’s a notorious sequence that stills winds up and offends viewers, especially those who separate sexual encounters into the unambiguously consensual and plain violation.

Elsewhere, the mini-skirted teenage daughter of the village’s main troublemaker (a burly, menacing Peter Vaughan) is a flirtatious voyeur whose undisciplined nature has given way to precocious sexuality. Straw Dogs shows female sexuality can be a dangerous lure that not only leads the opposite sex into all kinds of bother, but lights the fuse of unbridled violence, a violence that men like David Sumner have little idea is already bubbling away within. Whether Peckinpah condones that aggression as a necessary way to protect territory and establish manhood (“This is where I live. This is me. I will not allow violence against this house”) is still being debated today.

The Getaway (1972) ‘Punch it, baby!’

A Walter Hill (The Driver, 48 Hrs) script. Steve McQueen tearing up the screen. And Peckinpah in the director’s chair.

Oh, boy. This is what you call proper filmmaking.

McQueen is Doc McCoy, a convicted bank robber struggling with a ten-year sentence in Texas. Luckily, his loyal, resourceful wife Carol (Ali MacGraw) knows a trick or two. One such maneuver involves wearing a low-cut blouse and sauntering into the office of the corrupt, highly influential businessman, Beynon (Ben Johnson). Ten minutes later Doc’s back on the street, knowing there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Now under Beynon’s thumb, he must take part in a bank robbery, but isn’t even allowed to choose his own men. “You run the job,” Beynon tells him, “but I run the show. And don’t forget it.”

The Getaway is notable for its terse dialogue. Peckinpah establishes so much in the opening ten minutes you realize what a brilliant visual storyteller he is. Talk about show don’t tell. There’s hardly a word spoken, but Doc’s pent-up frustration with the monotony of convict life, the undimmed love for his wife, his dislike of Beynon, and the tantalizing sense of freedom represented by the grazing deer on the outside of the prison’s fence are all effortlessly conveyed. Even when a contemptuous prison guard tells him “You’ll be back” while opening the gate, Doc doesn’t reply.

It’s not that kind of movie.

Doc is the personification of blue-eyed, ice-cold professionalism, but four years in the slammer has made him rusty. Plus, he’s no longer working with a top crew. In particular, Rudy Butler (Al Lettieri in wonderfully slimy, vet-humiliating form) is an arrogant, duplicitous fucker who thinks the imminent job will be a ‘piece of cake’.

The complications that ensue from the meticulously planned robbery feel natural and believable, leading to such memorable scenes as an encounter with a smalltime con artist aboard a train, a none-too-rosy jaunt inside a garbage truck and a fucking ace hotel shootout. The shotgun-wielding, wife-slapping Doc is a tremendously amoral character, although he gets typical help from Peckinpah’s thoroughly engaging cast. It’s my favorite McQueen movie and proved to be the biggest hit of Peckinpah’s career.

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974) ‘We’re gonna find the golden fleece, baby.’

Peckinpah followed Getaway’s big success with the studio-mutilated, ponderous and barely coherent Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Like Wild Bunch it’s about changing times. Or as one character says: “Country’s gotta make a choice. Time’s over for drifters and outlaws.” Billy’s a typical Peckinpah anti-hero in that he’s a piece of shit who contributes fuck all to society, but he’s got his code and initially you can’t help but be interested in what he’s gonna do next. Unfortunately, he’s portrayed by the far too old Kris Kristoffersen, a casting decision compounded by the man’s inability to play mean.

Garrett died at the box office. The director’s cut was released fifteen years later, forcing a reevaluation with many fans seeing it as of the era’s great westerns. They point to its authentic feel, the lovely cinematography and some very strong scenes e.g. a gut-shot Slim Pickens stumbling away to sit by the river as his stricken wife can do nothing but watch while Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door plays. However, I still think the flick lacks momentum and becomes repetitive.

Its commercial failure meant Peckinpah was in need of a hit so he set up shop in Mexico for the low-budget Alfredo Garcia. It not only died on its ass as well, but probably attracted the most scathing reviews of his career so far. Still, at least Peckinpah could claim it was the only one of his fourteen flicks completed without studio interference.

Unlike Garrett, I love the gloriously off-kilter Garcia, especially its opening in which a heavily pregnant teenager lies beside a sun-dappled pond as ducks and geese glide by. Peckinpah’s lyrical scenes are often overlooked by our moral guardians obsessed with his penchant for slow-mo, bullet-riddled deaths, but watch carefully and there’s plenty of nuance, tenderness and humor in his films. Garcia’s beginning is a classic bit of misdirection, though, because things soon turn startling.

The expectant girl is brought before her obviously powerful dad in a packed room. “Who is the father?” he asks.

A shake of the head.

Two henchmen rip her dress open to expose her breasts as the mother anxiously looks on, too intimidated to intervene. Jesus Christ, what kind of dad is this? The girl’s arms are twisted behind her back as she is forced to the floor crying.

“Who is the father?” he repeats.

Another shake of the head.

An arm is heard snapping, resulting in a name finally being given up.

Then this teary-eyed Mexican crime lord says Garcia was ‘like a son to me’ before putting a million-dollar price tag on his head, a bounty that ensures word spreads far and wide.

Fuck, what a brilliant opening, told (as usual) with Peckinpah’s marvelous directorial shorthand. Already we’re knee-deep in toxic masculinity, a sleazy, dangerous world of hard drinking, grieving grave robbers and gun-toting gay hit men where women get knocked out cold or sexually assaulted. I can’t recommend the blackly comic, increasingly unhinged, nihilistic nastiness of Garcia highly enough.

Cross of Iron (1977) ‘I will show you where the Iron Crosses grow.’

Lice, diarrhea, throat-slitting, furtive homosexual affection, a birthday celebrant taking a bayonet in the guts and children being machine-gunned… Welcome to the 1943 Eastern Front.

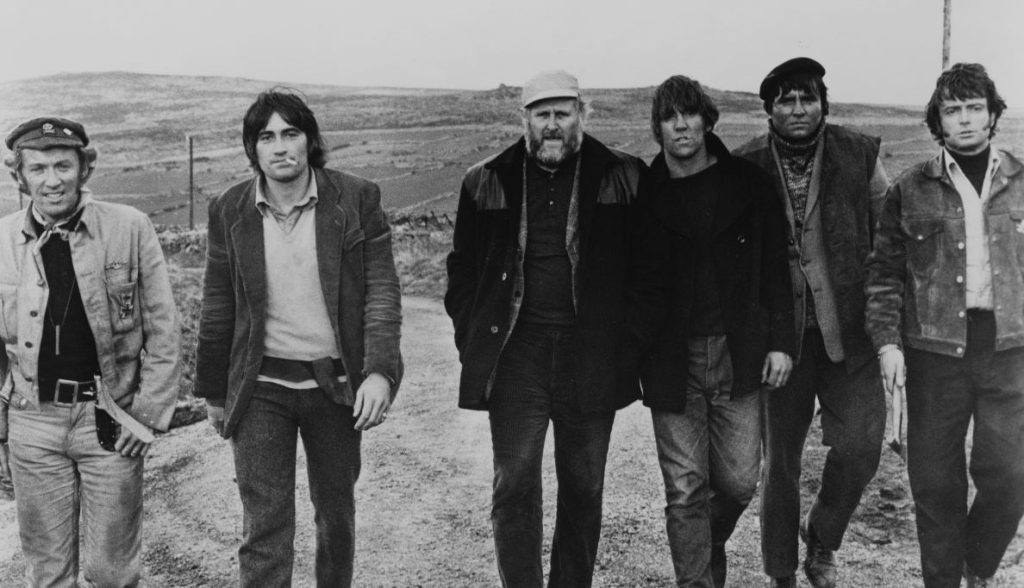

The Germans are in disarray, suffering constant shelling as they cower in their makeshift bunkers. Corporal Steiner (James Coburn) is a grizzled, insubordinate warrior, an unpatriotic cynic who believes God is a sadist but probably doesn’t even know it. He hates officers, but is fiercely loyal to his own reconnaissance platoon, a motley crew of experienced killers.

When Steiner is badly concussed he is shipped to a military hospital. His recuperation has a tinge of surreal horror and black comedy, as exemplified by a double amputee giving a visiting general a contemptuous Nazi salute with his leg. However, it is in this much safer and more civilized place that we start to get some understanding of Steiner’s yen to be in the midst of slaughter. He romances a buxom nurse and is told he is being given home leave as a reward for his decorated service. Things are finally looking up for the old dog, but when one of his subordinates turns up he instantly makes the decision to once again take charge of his platoon. This is an intelligent, self-aware man yet he wishes to return to one of the most dangerous places on Earth. Why would anyone do this? His tear-stricken nurse can only say: “Do you love the war so much? Or are you afraid of what you’ll be without it?” Steiner tells her he has ‘no home’, a belief that echoes David Sumner’s last line in Straw Dogs. Steiner is a typical Peckinpah protagonist, drawn back to violence and the possibility of annihilation because of some deep-rooted manly code he must obey.

Cross of Iron was Peckinpah’s sole war flick which is a bit of a shame as a straightforward focus on combat seemed like a natural fit. He gives us two hours of authentic mayhem, blowing the shit out of almost everything on screen. He also finds time for some poetic images, such as a dead soldier face down in a water-filled ditch, his newly shed blood blooming around his head. Performances are excellent throughout, especially James Mason as Steiner’s sympathetic superior and the deceitful Maximilian Schell as an ‘aristocratic pile of Prussian pig shit.’ The indestructible Steiner endures air raids, a gripping Russian tank assault, and his men’s stinky, bunker-enclosed farts while women, as usual, are sexually assaulted.

This was Peckinpah’s last hurrah, following Cross with two inferior flicks before his relentless substance abuse ensured his own self-destruction in 1984.