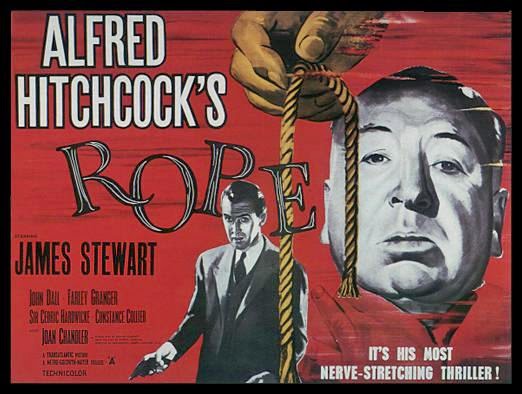

Flanked by Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and Strangers on a Train (1951), Rope.

A budding pianist anxious to know if his debut concert will be a success, Philip asks Mrs. Atwater to read his palm. She grants his request and says: “These hands will bring you great fame.” Her prophecy should please him, but Hitchcock shows us Philip’s hands, the hands of a strangler, fingers frozen in the posture of their deed; then the strangler’s terrified face. It would seem Philip already knows the fame Mrs. Atwater speaks of is, in fact, infamy.

(1948) serves as the centerpiece for Alfred Hitchcock’s strangler trilogy, a three part meditation on murder, reading, and the ‘ordinary.’ In his well known study of Hitchcock, Francois Truffaut remarks that Strangers on a Train “just like Shadow of a Doubt is systematically built around the figure two.” In both pictures the two central characters “might very well have had the same name. Whether it’s Guy or Bruno, it’s obviously a single personality split in two. Rope also fits Truffaut’s schemata as Philip and Brandon, like Charles Oakley and his niece, and Guy and Bruno, form “a single personality split in two.” Philip’s hands, like Charles Oakley’s and Bruno Anthony’s, have a will of their own. Hitchcock endows those male hands with a characteristic usually associated with the phallus. To revise an old chestnut: these hands when aroused have no conscience.

As Charles Oakley converges on his niece and alter ego with murder in his hands, she suddenly stares at his pulsing claws and cries, “Uncle Charlie, your hands!” Aroused by fear of what his niece knows, he is intent on committing what might be called a lethal act of incest. The sexual stirrings alive in the act of murder are likewise present when Philip doesn’t want Brandon to turn on the light, but wishes to remain quiet, like lovers in the dark, after killing David Kentley. Brandon even lights a cigarette. When Bruno stalks Miriam, the wife who won’t give Guy a divorce, she clearly interprets his interest as sexual. He plays the strong dominant male for her by rubbing his hands together, grabbing the hammer, and ringing the muscle-man bell at a carnival. We are told by the barker he breaks it, proving himself a real man as opposed to the two teenage-looking boys Miriam is with. Through her eyes we see Bruno lowering his victim to the ground as he strangles her. He is ‘laying’ her. The murder might as easily have been a rape.

I place Rope at the center of the trilogy because in it madness, reading, and the ‘ordinary’ interweave in a pointedly philosophical manner. Brandon and Philip exercise their ‘privilege’ as superior intellects to commit murder. Their teacher at prep school, Rupert Cadell, had introduced the boys, particularly Brandon, to Nietzsche’s concept of the Superman.

Philip and Brandon embody the split in Crime and Punishment’s haunted protagonist. The former is guilt ridden, the latter triumphant. From the first minute after David Kentley’s death, Philip seems to reject what his hands have done. He looks upon them now in fearful awe. We watch him rubbing his hands together as if to soothe them and telling Kenneth, an old school chum: “It seems I’m to be locked up.” We could at this point easily imagine a confession, but here the stronger Brandon steps in to explain that Philip will be in seclusion at Brandon’s mother’s country home until his debut as a concert pianist. Philip breaks a glass and cuts himself when Mrs. Atwater mistakes Kenneth for her nephew, the murder victim. Philip’s guilt erupts yet again when he cannot bring himself to pull the murder weapon, a short length of rope, out of a chest that holds David’s corpse and from which food will be served for a party.

For Brandon, killing David puts flesh on the image he has of himself. He had, in his mind, committed the ‘perfect crime’, employing Philip as his executioner. Whether Philip’s hands on a piano or the neck of a victim leave Brandon in awe, or are simply useful tools for the latter’s plans is a question worth considering. Brandon tells Kenneth he arranged for Philip’s debut concert. Had the killers not been caught, would there have been a concert? Might Philip have wound up at the bottom of a lake with David? I think he would have.

Brandon displays his ‘courage’ with everybody but Rupert, before whom he stammers like a schoolboy. Brandon stands by his actions as one would expect of an ardent follower. With Philip Brandon is particularly forceful, at one point even slapping him. Seemingly not for the first time in their long relationship.

When the two argue about feelings and weakness, Brandon has the last word. He says, “Being weak is a mistake” to which Philip replies, “Why because it’s being human?” Brandon retorts, “Because it’s being ordinary.” Brandon is in revolt against the ordinary as are Bruno Anthony and Charles Oakley. The former, upon meeting Guy, wastes no time portraying himself as a seeker of dangerous thrills. He does not repeatedly employ the word ordinary as Uncle Charlie and Brandon do, but Bruno has no intention of being an ‘ordinary’ guy who works for wages and keeps regular hours. Charles Oakley’s loud and reckless remarks at the bank where his brother-in-law works are meant to slap the ordinary Joe (his brother-in-law’s name) squarely in the face. He deposits forty thousand 1943 dollars in cash, all the while denigrating the effort to acquire money.

Charley Newton tells the ‘survey taker’ detectives: “My uncle’s opinions aren’t average…” She later admits not liking to think of herself as ‘average.’ The term ‘average’ is introduced by Jack, the detective masquerading as a survey taker and stands in nicely for ‘ordinary.’ In response to Charley Newton saying she doesn’t like being an average girl in an average family, Jack says, ‘Look at me. I’m an average guy from an average family.’ Jack celebrates being average, being ordinary.

Reading is of course an oft-used escape from the ordinary. The strangler trilogy associates it with youth and childhood, and addresses both highbrow and lowbrow reading. The former appears to be furthest from the ‘ordinary.’ Brandon speaks of reading on two occasions. Once when he is explaining Rupert’s belief that people not only read but can understand what they have read. And a second time when Mrs. Atwater remarks that she did a lot of reading as a child. Brandon responds: “We all do strange things when we’re young.”

The books (‘first editions’) David’s father, a collector, has come to inspect are of course symbolic of the ideas Rupert introduced to the killers. Dangerous ideas, but then we must not forget: ‘Any idea that is not dangerous, is not truly an idea at all.’ The books are then accomplices to the murderers while the rope used to kill David runs parallel to the inscribed emerald ring Charles Oakley gives Charley Newton in Shadow of a Doubt and the cigarette lighter Bruno Anthony clings to with his last breath.

As a boy Charles Oakley read a lot before his near-fatal bicycle accident. “Let me tell you,” his older sister, Charley Newton’s mother tells us, “he didnât read much after that.” Charley’s kid sister, Ann, is disappointed by their father Joe’s low brow, murder mystery magazine reading. We might be inclined to surmise that Joe’s lowbrow taste is emblematic of his harmless nature, that the rarefied cerebral regions of philosophy serve as a potential vehicle for unspeakable deeds while the reading matter of the ‘ordinary Joe’ contributes to a happy, loving nature; but Bruno Anthony pulls us up short. His reading comes straight from the daily newspapers, the sports and society sections. Apart from the opportunities afforded by his father’s wealth, he is rather ordinary; a spoiled and decadent rich boy. Conventionally Oedipal Bruno is, despite all the ‘I’m a man’ bravado, a teenage rebel in the body of a man pushing, if not looking back on, thirty.

Guy is something of a slippery character. At first glance he appears to be a golden boy, but then defends himself, perhaps, too quickly when Bruno compliments him on his forthcoming marriage to a senator’s daughter. Likewise he is hurt when his fiance asks him how he got Bruno to kill Miriam. But then why wouldnât a genuine golden boy react exactly as Guy does? Yet to paraphrase Psycho’s Detective Arbogast: something doesn’t jell. It needs to jell. Guy seems ready for Bruno’s remarks as he was for Ann’s; ready, even waiting for them. Truffaut doesn’t trust Guy, refers to him as ‘an opportunistic playboy.’ The last words we hear from Guy are in response to a carnival worker asking him who the man killed in the carousel crash was, to which he replies: ‘Bruno. Bruno Anthony. A very clever fellow.’ To my ear, this remark mocks the dead man. Bruno is ‘a very clever fellow,’ but not so clever as Guy.

The manner in which the trilogy toys in an explicitly comic way with murder seems to underscore the need for not taking one’s beliefs too seriously while at the same time displaying possibilities ‘civilized’ society does its best to ignore. Mr. Kentley’s defense of ‘civilized society’ notwithstanding. In Rope Rupert speaks of murder with a wit everyone but Mr. Kentley, and possibly Philip, finds entertaining. Strangers on a Train has Bruno parodying Rupert’s take on murder but going too far and nearly choking a woman to death while in Shadow of a Doubt Joe and next door neighbor Herb use a running game of devising ways to kill each other as a method of relaxation.

Hitchcock’s playfulness inserts the comic touch for which he is so rightly acclaimed, but the strangler trilogy’s primary concern is the concept of the ordinary, the average. We have already seen the idea of being ordinary or average rejected by Brandon, Bruno, and both Charley Newton and her uncle. Jack appears to be a vehicle for wisdom as he speaks and acts in a moderate, average, ordinary fashion. Perhaps most importantly, he represents the law. Despite Rupert’s status as an intellectual the dark implications of his role in Brandon and Philip’s development seriously tarnish any claims he might have to wisdom.

All three films illustrate the dangers of not being ordinary. Hitchcock’s strangler trilogy brings to mind an Anton Chekhov short story appropriately titled, The Murder, in which a man who others believe to be a saint falls “into fornication” and upon seeking the advice of a devout and well-respected elder is told: “Be an ordinary man. Eat and drink, dress and pray like everyone else. All that is above the ordinary is of the devil.”