Alexander Payne’s Nebraska is the story of an America not so much in decline as it is, well, “at rest.” God’s country in the prone position. Where the pursuit of happiness yields to a much more illustrative and natural state of perpetual self-loathing, with unexamined anger as instinctive as breathing. A nation where the expectation of sudden and unearned riches has reached such fevered insanity that we can no longer even be bothered to buy a ticket. Instead, and quite naturally, the tickets come to us.

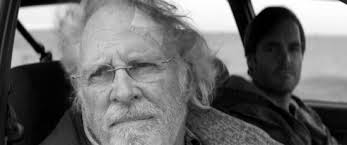

It’s gotten so bad that even our layabouts are making demands. Enter Woody Grant (Bruce Dern). While he long ago stuffed his rage into the empty liquor bottle of your choosing, he’s nonetheless arrived, stumbling and unkempt, at the only real destination such men are afforded wholesale inaction. He is a man with no real future; a past now clouded by distortion and evasion, and a present so without conventional cues of continuation that he’s resorted to the expected single-mindedness to justify tomorrow. Or even the next few hours. Like so many, he clings to a dream. More delusion, really, but a place to go, with a purpose well-served. He has an odd promise, really, when his life has been defined by exactly that, only one routinely broken and the world will fall away into silence until it’s been fulfilled.

Woody, it would seem, is a millionaire. Not by the standards of any objective reality, clearly, but on the grounds of something far worse a written guarantee. It’s a prize notification from Lincoln, Nebraska, and while an obvious fraud to all but himself, he’s bound and determined to claim his reward. And if he has to walk from Billings, Montana to do so, then that’s what his life has come to, after all. Surely even Woody knows the score what man alive in our recent century would not assume that anything and everything wasn’t burdened by the proverbial “catch”; but the very existence of such cons testifies to at least a partial success rate.

Someone is answering these letters as if they’re holy writ. Of course, one is inclined not simply to ascribe the expected stupidity to Woody’s mad quest, preferring the much more reasonable explanation that even if it’s a lie, a lie is still reason enough for getting out of bed. Woody, from all appearances, is shot through with the expected misfortunes of a life poorly lived, and even at this late date, a nearby spouse isn’t enough to shake loose the doldrums. His marriage, having long since graduated from endurance test to protracted stalemate, is now little more than a death watch. If a reason remains at all to continue, it’s simply to see the old bitch buried.

And so, the quixotic journey. For if the American cinema has revealed anything about our lives, it’s that when we’re cornered or frightened or seeking succor, we take to the open road. Most of us learn not a thing on these adventures, often returning with little more than tire wear and credit card debt for our troubles, but we remain convinced that what our home lacks, faraway lands will provide. The movies sure have us believing such romantic folly, and we could pack an entire festival with wall-to-wall examples of the very same. Fortunately, Nebraska is not trafficking in the familiar. The trappings, yes, – highways, back roads, small towns, seedy bars, and coffee shops – but not the result.

Woody is not at all appealing when we first meet him, and he remains defiantly unchanged upon his exit. He completes whatever circle he believes to have been broken, but the world itself is none the wiser. Hearts are not melted, hand are not clasped, and knowing glances are so studiously avoided we’re hard-pressed to find much by way of emotional release. Dad’s a drunk, his wife, Kate (June Squibb) an unrelentingly mean, gossipy bitch, and the son tasked with driving the old buzzard between the two locations, David (Will Forte), is baffled, disgusted, and impatient by turns. He’s not heartless, but neither is he about to sing anyone’s praises. He can’t even keep a woman who’s beneath him.

No, the Grant clan, far from bizarre in that fashion unique to the silver screen, is ultimately the most ordinary of the age. So painfully normal in their buried resentments and squandered desires, so earnest in their helplessness before an indifferent sky. It’s here that Nebraska hits all the right notes, refusing to extrapolate beyond the unassailable truth of our often-disorganized human relations. If David, for example, is incapable of grand gestures before his father, it’s because, to a man, we’ve all lost the capacity for that very thing. Instead, we pick around the edges of our lives, substituting terse, obligatory words and movements for the larger meaning we claim to seek.

As such, a father and son fail to breach the divide in exactly the manner you’d expect a husband and wife to avoid the very breach itself. We have-not the tools, emotionally or otherwise. Whether we ever had it at all remains debatable, but here, in this world, it’s clearly implied that something was lost along the way. Something within the scope of memory; something still recognizable if we gave a damn about its resurrection. It’s here that the black and white cinematography settles in for its greatest justification. Bleak doesn’t even begin to describe it. What jobs remain aren’t worth getting. Towns cling to past glories like weeds upon a dreary half-acre of abandonment. And love is like the light that long ago left a dying star.

Again, there’s no real reason to humor the old man at this stage, especially when it’s unlikely he’d ever have returned the favor in kind. He explains his motivations as wanting to leave his kids a little something, but that’s less an act of generosity than an admission of past sins. If it’s guilt alone that brings about that third act release, it’s better to leave honestly, if painfully. And maybe that’s enough for David, to see his father alive and committed one last time, if not for the first time. Even a visit to Woody’s boyhood home is anticlimactic; more obligatory look than cause for examination. He lived well beyond expectation without once pausing for an inward glance, so why start now? Some might see old rooms, old walls, broken fixtures and the like, and feel the sweeping rush of history. Most would be overcome to some degree. Woody sees mere decay.

Why preserve what we can’t change? Why re-live what’s lost to all but the keenest of memories? You did what you did, and now it’s done. More so if you can’t see fit to regret it. Even regret feels self-indulgent. Woody and the decomposing mortar of prairie life are, then, one and the same. Sentimentality pushes us to preserve, but they’ve both had their time. Life and circumstance have had their say. Nebraska is one of the best cases for moving on that I can recall.

So, if one is inclined to dismiss Nebraska as minor, or obvious in its dismissal of sad, flyover America, complete with its ludicrous karaoke, unpleasant buffets, and glassy-eyed familiarity, it’s best to remember that no one’s claiming higher ground. Not Payne, not the actors, and certainly not the screenwriter. This is no winking satire of a buffoonery we’ve managed to escape. Instead, it’s an ode of sorts to the dying embers of family, yes, but also to the very idea that our apologies can and should be heard, even if no one is listening. I’m convinced we love and hate the ties that bind in equal measure, and that we cling to decency with such tenacity because we know its polar opposite is forever and always in the ascendency.

And like it or not, we’re the product of the very thing we know damn near killed us time and time again. So goes family, so goes the nation. Payne’s vision is of a land with nothing left to say about itself, and no one left standing to provide the eulogy. It’s barren, bereft, and ticking away to no real purpose. And so, we create. Stories, mostly, but always with an eye on distraction. Woody knows he’s dying in vain, dammit, but allow him a moment to pretend otherwise. The essential American.